How Alexei Ratmansky Brought A New Kind of Ballet to America

Marina Harss on the Ukrainian Choreographer's Clever Subversion of Artistic Expectations

In 2005, the Bolshoi Ballet paid a visit to New York. The company had a new young director no one in New York had heard of: Alexei Ratmansky. He was only thirty-seven and, though a product of the Bolshoi’s school, had never been a member of the company. Instead, he had had a respectable but not illustrious career dancing in Ukraine and Canada and Denmark. As it often does when on tour, the Moscow company, which is known for its extroverted and athletic style, presented a couple of old chestnuts, Don Quixote and Spartacus, as well as a nineteenth-century spectacle ballet, The Pharaoh’s Daughter. But the thing everyone was talking about was Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream, a farce set in the 1930s on a collective farm somewhere on the Russian steppes. It seemed like an odd choice to bring back what in Soviet times was known as a “tractor ballet,” extolling the virtues of communal life and productivity, accompanied by an energetic, cheerful—perhaps too cheerful—score by Dmitri Shostakovich.

What was this ballet? It should have been terrible: anachronistic, ridiculous, stylistically retrograde. And yet it was exactly the opposite: funny and silly and sad, filled with touching details that laid bare our flawed human nature. It included a hilarious (and ironic) parade of giant vegetables, a grand entertainment performed by the gathered farmworkers, a boisterous dance for an accordionist who imagines himself to be a sort of Rudolph Valentino, performances en travesti, a man in a dog suit riding a bicycle. And in the middle of all this, a romantic situation worthy of Beaumarchais, treated with the tenderness of Mozart. I knew I’d never seen anything like it. I was intrigued.

Dancers…were just people, albeit people who could do extraordinary things.I was also surprised. My eyes, like those of many American ballet lovers, had been trained in the cool, elegant modernism of George Balanchine. Like painting and music before it, ballet’s great advance in the twentieth century had been its move away from overt narrative and toward abstraction. Who wrote symphonies about the triumph of the spirit anymore? Who made story ballets? All you needed for a great work, Balanchine and others had taught us, was bodies moving through space to music (the drama was inherent in those bodies and the way they, and the choreography, responded to and expressed something deeply embedded in the music). Choreography, if it was good, was enough. In the late twentieth century, some choreographers had gone even further, deconstructing ballet’s technique and conventions (forget hierarchy, forget courtly manners, forget illusion). Dancers, they showed us, were just people, albeit people who could do extraordinary things. The question was, Where would ballet go from there? Was there anywhere left to go?

The Bright Stream, then, was a radical departure. It was everything a sophisticated ballet was not supposed to be: it had a tuneful score, clearly drawn characters, and a story rooted in a specific time and place. It used pantomime, something one simply didn’t see outside of the classical nineteenth-century ballets, and even there, the consensus was, a little went a long way. Mime! Everyone thought it was dead. Here the characters seemed perfectly happy to converse as well as dance. In this onstage world, contrary to Balanchine’s famous dictum about there being no mothers-in-law in ballet, there could be mothers-in-law, and cousins, and tractor drivers, and dogs on bicycles. And you felt you knew precisely who everyone was. And it was funny!

Sitting there watching it all, I felt two emotions at once: glee at the liveliness of what was unfolding before me and curiosity about the artist who had created it, someone who knew the tragic history of collectivization yet could poke fun at the idea of propaganda ballet, embracing its kitsch Soviet formula and yet making something stylish and clever and touching out of it. The ballet exuded irony, a very postmodern quality, but also—and this was the interesting part—warmth. Despite yourself, you cared about the characters.

This was because Ratmansky’s characters were not empty caricatures. They were people. It came through clearly in the characterizations of the Bolshoi dancers. In Don Quixote and Spartacus, performed that same week, they had been emphatic and ham-handed, like actors shouting at the top of their lungs, but here they were nuanced, specific, expressive, and really funny, more like characters in a French farce than figures in a grand spectacle. It was clear that great care had been taken in the development and honing of every role. Even better, you could feel the distinct personality of each dancer shining through the mask of his or her character.

Add to this the musicality of the choreography. It was as if every idea Shostakovich had developed in the music had found its equivalent in the steps Ratmansky devised for the dancers. Sometimes Ratmansky’s musicality was lighthearted, as in a scene in which a girl milked a cow—the udders were a dancer’s fingers—in time to the music; sometimes his way of interpreting the music created its own images. A whirring in the strings and woodwinds became an undulating movement for the arms, like the moving parts in a machine. But in every case the steps helped the viewer to hear the music better, to catch its jokes and see its layers of subtext. I wasn’t the only one who felt this way, it turned out. At the end of the intermission, as Ratmansky was returning to his seat, the choreographer Mark Morris stopped him in the aisle. “Baby, you’re the top of the town,” he told the startled Ratmansky.

I left the theater elated and full of questions. Who was this choreographer? What else had he done? The worlds of Russian and American ballet were far enough apart that his name was known only to a few ballet specialists in New York. But before the year was out, it had been announced that Ratmansky would make his first work for New York City Ballet the following season.

By 2008, three years later, Ratmansky had decided to leave Moscow for New York. I had my first interview with him the following year, when he joined American Ballet Theatre (ABT) as artist in residence, a position he holds until the end of 2023. In that conversation I was struck by his reticence and his resistance to overanalysis, paired with a kind of gentleness expressed through impeccable manners. For someone who had directed one of the largest, oldest, and most fractious companies in the world, he seemed to have surprisingly little ego.

The other thing that shone through was his unquestioning devotion to the art of ballet. At the time, a new history of ballet, by Jennifer Homans, had just come out, with an epilogue suggesting that it was a dying art. “You know, even if she is right,” Ratmansky said of Homans, “I don’t care. I do what I love.” He didn’t seem to worry too much about what other people thought. He had utter conviction in the art itself.

In 2019, a year before the Covid-19 pandemic struck, Ratmansky celebrated his tenth anniversary with American Ballet Theatre. In those ten years he had created almost fifty ballets for companies around the world. He has now endured a pandemic. He becomes restless when he’s not working. His former boss at ABT, Kevin McKenzie, told me once that he thought Ratmansky was a “creation junkie.” I think he may be right. I asked him once how he felt after finishing a ballet. “You feel very light because you’re so empty,” he answered. Was it a good feeling? I asked. “Yes, as long as it doesn’t go on for too long. Two or three weeks is perfect.” The pandemic forced him to stop for almost a year. It was a strange sensation for him, almost like not existing. Then came Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the place where he grew up and where his family still lives. His sense of self was deeply shaken. He kept working.

In 2017 I stood in Ratmansky’s living room in a nondescript high-rise on the east side of Manhattan as he and his wife, Tatiana, showed me some steps from a ballet he was working on. It was August. He was wearing flip-flops and shorts; she was in a light summer dress. The room wasn’t particularly large, so sometimes, as they moved, they ended up in the kitchen. He would catch her after a turn, and she would go through the motions of flitting away from him with a few quick jumps. (She was one of the first people he choreographed for and is still his most trusted adviser and frequent choreographic assistant.) They were relaxed, laughing, and I realized what an extraordinary thing I was seeing. Ballet is not something formal or abstract to Ratmansky—it is his natural habitat, the language in which he feels most conversant, his home, the air he breathes.

It’s unusual to be around a person so at ease with what he does, whose training and temperament and intellectual curiosity appear to be in complete harmony. This was what I intuited when I saw The Bright Stream, and what I felt even more palpably that first time we spoke. This impression has only intensified with every conversation that has followed, every rehearsal I’ve watched, every ballet of his I’ve seen. Everything besides creation is secondary.

The desire to understand that singular drive made me want to write this book, which is based on years of watching Ratmansky’s ballets onstage, of sitting in studios while he works with dancers during the creation process, and on interviews with him and with people who have known and worked with him throughout his life. I interviewed his parents and his sister, Masha, in Kyiv, schoolmates from his Bolshoi school days, dancers and ballet masters who worked with him at the National Ballet of Ukraine, and colleagues from the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the Bolshoi, the Mariinsky, American Ballet Theatre, New York City Ballet, and many other companies. I watched countless videos from his private collection of recordings. But most important, over the course of four years I had the pleasure of spending many hours speaking with Ratmansky himself, as well as with his partner in crime and art (and wife), Tatiana. Those conversations have infinitely enriched my impressions and understanding of his work, as well as of the person behind them.

__________________________________

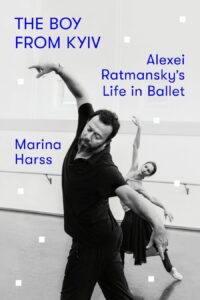

Excerpted from The Boy from Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet by Marina Harss. Copyright © 2023. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc. All rights reserved.