How Airline Stewardesses Fought Their Industry’s Toxic Patriarchal Norms

Nell McShane Wulfhart on Feminist Rebellion in the Unfriendly Skies

On April 17, 1963, eight stewardesses held a press conference in New York’s Commodore Hotel. Boasting toothy smiles, glowing skin, and impeccably pressed uniforms that displayed plenty of leg, they lined up in front of the gathered reporters and defied them to guess which of the stewardesses was over the age of thirty-two. Barbara Roads, aged thirty-five and known to everyone as “Dusty,” issued a challenge: “Do I look like an old bag?” she asked, with an audacious grin.

The stewardesses, all slim and smiling, were between twenty-three and thirty-six years old, and this stunt made headlines around the country. The answer to Dusty’s question was a loudly expressed no, both from reporters and the readers who saw the photo in their daily paper and took their own guess as to which of the stewardesses was over the limit. The Daily News described Roads as “poured elegantly into a form-fitting uniform (measurements, 36-24-36)… Dusty stands a long-legged five ft. eight and weighs one-hundred-twenty-five pounds and has natural blonde hair, if you get the picture, fellows.”

Dusty, a charming, strong-willed stewardess, was an ALSSA leader, and she and her close friend Nancy Collins had organized the event to call attention to the age issue as the union and the airlines battled over the automatic-termination-at-thirty-two rule. Dusty, who had been hired in 1950 before the rule was implemented, wasn’t even affected by it—according to the arrangement made between American Airlines and ALSSA, she’d been one of the group “grandmothered” in, and could continue flying even past her expiration date.

The age issue went all the way to Congress. Dusty had been petitioning members of Congress, schmoozing them, even dating them, in an attempt to get a law passed that would permit stewardesses to stay on the job past thirty-two, but to no avail. Then, in 1965, federal hearings were held on employment issues faced by older workers. Could they get rid of the age rule this way? The stewardesses decided to try.

Passengers had been trained to expect young, smiling women welcoming them into the cabin, not women with gray hair and lines etched on their faces from all that smiling.

A group of seventeen stewardesses, including ALSSA president Colleen Boland (age thirty-six) and Northwest stewardess Mary Patricia Laffey (age twenty-seven), headed to Capitol Hill to testify about the airlines’ retirement policy. The House of Representatives Select Subcommittee on Labor was considering the issue of age discrimination in employment, debating whether to create a law against it and, if so, which ages should be protected.

They included the stewardesses in their debates over age discrimination and related problems, and hopes were high that Congress could force a change on the airlines. The women appeared before a three-man panel that seemed to view their presence as more of a joke than anything else. Representative James H. Scheuer even asked Colleen, “Would you be good enough to have the members of your group stand so we can visualize the dimensions of the problem?”

Colleen delivered a strong statement, hammering home the point that age had nothing to do with a stewardess’s ability to do her job. But the congressmen were more interested in the view than in what she had to say. Representative Scheuer asked, “Would the airlines tell us that these pretty young ladies are ready for the slag heap?” He followed this with the generous statement, “I for one would oppose to my dying breath the principle that a woman is less attractive, less alluring, and less charming after age 29 or 32 or 35. I think my colleagues on this committee will agree.” Representative James G. O’Hara responded, “Especially if we want to be reelected.” Cue general laughter. When Colleen finished her testimony, O’Hara expressed his appreciation to her and her fellow workers “for adding some beauty and grace” to the hearings.

The proceedings came to an end without any progress on age discrimination; the government had nothing to offer stewardesses who crossed the invisible age line. The women were bitterly disappointed. They had, though, made the news: the papers avidly covered the hearings, with titillating headlines such as “Airline Stewardess over the Hill at 32? Congressional Girl-Watchers Say ‘No!’ ” (the Atlanta Constitution) and “Stewardesses Pushing 32 Stack Up Well in Age Plea” (the Baltimore Sun). But it was paltry compensation.

Firing stewardesses at the age of thirty-two didn’t always mean that the women disappeared at that age. Some were reassigned to ground jobs, though these were usually lower status, paid less, and might involve moving to another base in a completely different part of the country. Many stewardesses who aged out found employment at the Admirals Club (the airport lounge for valued customers), and the few who had been grandmothered in still worked the line. They became known as “gold wingers” because after five years of service, the silver wings that had been pinned on them at graduation were exchanged for gold ones.

Patt became friends with a gold winger, Ann Davis, and they often flew together. Passengers boarding the plane would see Ann’s gray hair and crack jokes (“Oh, look at this, a mother-daughter team!”). Ann would laugh and smile, saying nothing; Patt followed her example. One day they had to prep the plane for an emergency evacuation, and Patt noticed that suddenly none of these wisecracking passengers wanted to talk to her anymore. They directed all their questions to Ann, seeking reassurance from the woman who clearly had more experience.

All at once the human toll of the age discrimination issue was made real to Patt, who’d signed her contract without a second thought. Pilots had gray hair, she realized, and no one cared.

All at once the human toll of the age discrimination issue was made real to Patt, who’d signed her contract without a second thought. Pilots had gray hair, she realized, and no one cared. It wasn’t long afterward that Patt and Ann were in Operations waiting for a flight. Bob Ferris, the base manager, was walking out the door when he caught sight of them. “Hey, Ann!” he shouted. “Why don’t you wear silver wings instead of your gold wings so they match your hair?” He guffawed at his own joke as he left the room, but Patt didn’t laugh. And for Ann it wasn’t anything new; it was just one more dig, one more unsubtle encouragement to leave the line.

The airline eventually convinced Ann to resign by promising her a job as an instructor at the charm farm. She had finally tired of the jokes, the spoken and unspoken pressure to get out of the cabin and make way for the younger women. The disappointed faces of male passengers who’d clearly been expecting a fresh-faced twenty-year-old started to undermine her confidence. So she took the instructor job. When she arrived, though, she found herself put in charge of supplies instead.

Keeping track of inventory felt like a token job to Ann. It wasn’t instructing, it wasn’t working the cabin, it wasn’t important. She couldn’t stop thinking about how she was too old to be on the airplane, too old, according to American Airlines, to even appear in front of the public. She became depressed. After a few months, she suffered a nervous breakdown, and she checked herself into a psychiatric hospital for treatment. But it didn’t help. She hadn’t been there long before she committed suicide, suffocating herself with a plastic bag she’d found in a garbage can. She had left behind, Patt would learn, a note. It said that she felt old and useless.

She couldn’t stop thinking about how she was too old to be on the airplane, too old, according to American Airlines, to even appear in front of the public.

Ann Davis wasn’t the only stewardess over thirty-two who committed suicide. She was one of six individuals who had been forced off the line for being too old and had been unable to come to terms with being discarded after years of service. Appearance was everything at the airlines when it came to stewardesses, and passengers had been trained to expect young, smiling women welcoming them into the cabin, not women with gray hair and lines etched on their faces from all that smiling.

As the stewardesses were fruitlessly looking for help from Congress, the airlines decided to double down on marketing their sexual appeal. The industry started launching advertisements and uniform changes that would get more and more extreme, veering at times into the truly bizarre. In 1965, Patt and her fellow stewardesses watched in disbelief as Braniff International Airways took the lead, hiring designer Emilio Pucci to revamp its uniforms. The new look included futuristic clear plastic bubble helmets to keep off the rain, skirt suits, shift dresses in primary colors for serving dinner, and knee-length “harem pants” with tight-fitting mock turtlenecks for dispensing digestifs. Braniff then debuted the “Air Strip.” During the flight, its stewardesses would, bit by bit, shed pieces of their elaborate new uniforms.

The print ads, bright with color and seductive smiles, portrayed the whole event as a striptease—who knew where it might end? The television commercial, set to bawdy flute music, featured a woman unzipping a coat, then slipping off a shoe, then unwrapping a skirt, as a man’s voice intoned, “When a Braniff International hostess meets you on the airplane, she’ll be dressed like this…When she brings you your dinner, she’ll be dressed this way…After dinner, on those long flights, she’ll slip into something a little more comfortable… The Air Strip is brought to you by Braniff International, who believes that even an airline hostess should look like a girl.” There was also a Braniff Barbie, who came with four stewardess outfits. Ken, in his pilot uniform, was sold separately.

The fitted nature of the eye-catching new clothes meant that stewardesses even had to remove their girdles. Unashamedly performative, the new job description for a stewardess was less about safety than it had ever been before. This campaign, along with “the end of the plain plane” (Braniff painted their planes in seven new colors, including blue, yellow, orange, and turquoise), was the brainchild of Mary Wells, advertising’s best-known female executive. Gloria Steinem would later say that “Mary Wells Uncle Tommed it to the top.” Wells issued a blunt rebuttal: “I worked as a man worked. I didn’t preach it, I did it.”

A year later, Braniff reported a nearly 50 percent increase in revenue. The “Air Strip” pointed the way: stewardesses were now a financial driver.

Featured image: Patt (on the right) in grooming class; grooming instructor Kelly Flint on the left. Courtesy of Nell McShane Wulfhart.

___________________________________

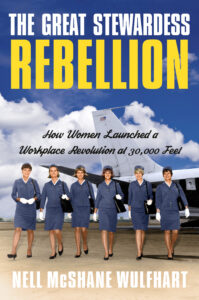

Excerpted from The Great Stewardess Rebellion: How Women Launched a Workplace Rebellion at 30,000 Feet by Nell McShane Wulfhart. Copyright © 2022. Available from Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Nell McShane Wulfhart

Nell McShane Wulfhart is a frequent contributor to the New York Times travel section and wrote the column “Carry On” from 2016-2019. She has written for Travel + Leisure, Bon Appétit, Condé Nast Traveler, The Wall Street Journal Magazine, and T Magazine. She is the author of the Audible Original Off Menu.