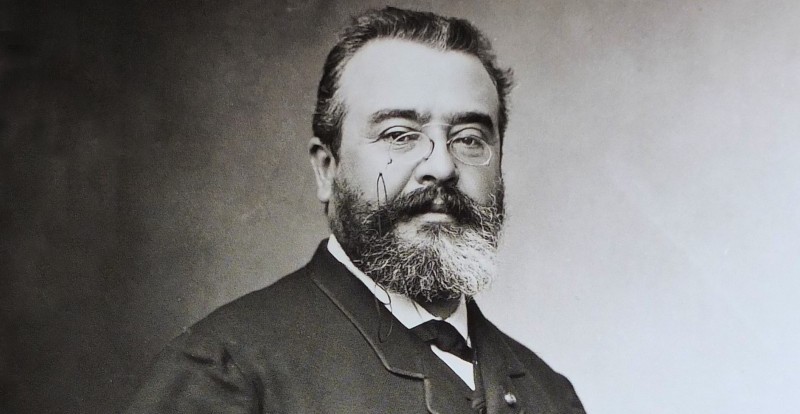

How Adrien Proust—Father of Marcel—Helped Pioneer Global Public Health

Simon Schama on Another Illustrious Member of the Proust Family

Some years ago in Paris, in a moment of idle curiosity, and for very little money, I bought a short book about Marcel Proust’s father, Adrien. Its author was the physician Dr. Robert le Masle (also a translator, writer and illustrator) who was a friend of Marcel’s younger brother, the urologist, Robert. The slight volume was meant as a commemorative tribute to the father of the brothers Proust thirty years after his death in 1903, but was published two years later in 1935. The delay, however, carried with it a stab of funereal poetry. That same year, le Masle and Robert Proust had made a pilgrimage to Illiers, the country town Marcel had turned into the idyllic ‘Combray’ of his childhood in a conscious revisitation of the expedition the family had made together in 1880. But in May 1935, Robert died, so the book became, between the lines, a double elegy.

I knew nothing of this at the time that I bought the book. It seemed to me then merely a literary gesture of high-pitched reverence. The vaguely antiseptic associations of Adrien’s career put me off doing anything more than taking a cursory glance at its pages. The most arresting thing about it, so I then supposed, was the commandment inscribed in English on the fly leaf, unsigned but dated July, vii, 1936: “He who would not live in hell / Should read the books of Proust, Marcel.” Who would disagree? Away it went, sentenced to captivity in the chaotic obscurity of my shelves. But in the “month of Mary,” as Proust called it, May 2020, a whole new interest in public health led me to search for and recover the book, which, as sometimes happens as if self-animated, opened to a page that revealed something I had missed on first acquaintance. Between its leaves, as if inserted as a Proustian memory-prompt, was a small sprig of hawthorn, the aubépine whose heady spring blossom switched on the sensual wiring of the boy Marcel. Appearing in church, hawthorn seemed to the tingling youth a synecdoche of all nature. But hawthorn also features prominently in any pharmacopeia as a stimulant of sturdy cardiac health. Which is why it seemed ironic that this particular dried but exquisitely preserved sprig, retaining on its stalk minute thorns, lay over the passage where le Masle describes Adrien’s death.

It was as a sentinel against the pandemics of the age…that Adrien Proust had become famous.

That demise on 20 November 1903 was, it was said, “inopportune—untimely”—a Proustian word, but fitting nonetheless. Adrien had been on the verge of a triumph, finalement, the realization of his plan for a permanent international agency for public health. He had been attending the International Conference on Sanitation, the eleventh since its inauguration in 1851. The 1903 meeting was Proust’s seventh; he had sat through them all in Vienna, Dresden, Venice and Rome. He had bided his time though not always minded his temper with the frock coats, the bespectacled and opinionated, the epidemiologists and—alas—the diplomats: the intense Germans, the aggravatingly oblique, dependably disingenuous, English. Washington, in 1881, had been a steamship too far, even though Proust knew yellow fever would be the focus of discussion and he had been developing a serious interest in that particular disease along with all the other epidemics and pandemics. At international conferences on pandemics, he had become an indispensable fixture. Le Figaro had called him “the founder of international public health.” That perhaps was a little much, but Dr. Proust would not have brushed the compliment away.

Some, the British especially, thought him pompous, arrogant, tiresome; others flattered his tirelessness. At sixty nine, on occasion he would succumb to moments of exhaustion, lowering himself on to the sofas of friends. He would rally, of course; it was expected of him. At the opening of the Paris conference in October 1903, he had given yet another speech on the absolute necessity of a permanent international public health agency. But while at all the other conferences he had registered the raised eyebrows, the rolled eyes, the theatrically stifled yawns, on this occasion it seemed possible that his vision of how the world would come together to manage pandemics might actually become fact. If such an institutional miracle was accomplished, it would be the capstone to his long career in public health. It had taken a mere forty one years of incessant campaigning, he joked to the gathering. But the long haul had worn him out. A beckoning finishing line can slow one down just as easily as trigger a sprint. It was undeniable, in his seventieth year, that he was noticeably more laborious: stouter; the broad, handsome face a little jowly; his brow creased; the carefully trimmed whiskers, silver. All the same, on 23 November, without taking his eye off the Eleventh International Conference on Sanitation elsewhere in the city, Proust got to his feet to address the annual meeting on tuberculosis, another of his special interests, along with infections of the brain, especially aphasia, about which he had written one of his many books. Aphasia—when a damaged brain makes vocalized words evaporate between thought and utterance—was a truly Proustian terror.

But it was as a sentinel against the pandemics of the age—cholera, yellow fever and obstinately persistent, terrifying outbreaks of bubonic plague—that Adrien Proust had become famous in the medical establishment of the Third Republic, and beyond into the monde of science and letters. Or rather, he was a campaigner against the many inside the medical profession still denying that those infections were contagious. Instead, they argued that epidemics were discrete phenomena, occurrence and virulence entirely conditional on local qualities in the soil and the air. Sir Joseph Fayrer, the conference delegate representing British India (they demanded two representatives, of course, one from Britain, another from the Raj), insisted that cholera was just a variant of malaria, as indeed were yellow fever and plague, and, moreover, that the cause was to be found in a disturbance of atmospheric electricity. Early warning of a pandemic might be folded into a weather forecast.

Marcel waited until his father was safely entombed at Pere Lachaise cemetery before lining his study with cork and fitting impenetrably heavy curtains.

On the morning following his speech to the lung people, Dr. Proust paid a call to his younger son. Dr. Robert Proust was already a successful urologist, a silver medallist in his professional examination: much for his father to be proud of, not that Proust père had exerted the least persuasion. Robert had studied with the charismatic founder of French gynecology, Samuel Jean Pozzi, a recruit to Sarah Bernhardt’s sizeable stable of lovers. In the last year of the Great War, Pozzi would be fatally shot by a patient who blamed the amputation the surgeon had performed on him for the onset of impotence. Not all wearers of prosthetic legs were as insouciant as Sarah, apparently. Robert Proust himself added gynecology and urology to his standing—admirers joked that his pioneering procedure of prostatectomy ought to be known as proustatectomy—and was successful enough to be able to afford an elegant apartment at 136 boulevard Saint-Germain. When his father arrived for a morning coffee on 20 November, Robert was immediately struck by his unusual pallor. Acting on family instinct, he insisted on accompanying Adrien to the Faculty of Medicine where the professor was to chair a committee examining a medical student’s dissertation. Just prior to that meeting, Dr. Proust Senior went to his lab and then, anticipating a long academic examination, paid a prudent visit to the lavatory. He failed to emerge. When Robert broke through the door, he found his father lying on the floor, paralyzed by a stroke. Adrien was taken to his apartment on the rue de Courcelles near the Parc Monceau where, two days later and without recovering consciousness, he died.

The funeral was an Event; le tout Paris, or, at any rate, all those who mattered, showed up at the Eglise Saint-Philippe-du-Roule on the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honore. Clinicians, epidemiologists, public health officials paid their respects, along with a former prime minister, Jules Meline, foreign ambassadors Scandinavian and Persian, French diplomats from the Quai d’Orsay, epauletted generals, and, notwithstanding the grieving Jewish widow who would survive her husband by just two years, a scattering of the amitiés amoureuses with whom (it was no secret) the deceased had been gallantly close (Laure Hayman, Marie van Zandt); also some of his elder son Marcel’s friends whom the doctor-professor had beamingly indulged in his expansive middle age: a Prince Antoine Bibesco, Mathieu, comte de Noailles, the poet Robert de Montesquiou and, of course, a Rothschild. Marcel and Robert were pall-bearers. As it had always been, their burden was weighty.

Adrien Proust had habitually called his elder son “mon pauvre Marcel” and, aggravatingly, continued to do so as the bronchial boy turned into the asthmatic man. There had been a time when the father, believing the asthma to be at least partly “neurasthenic,” prescribed the kind of tonics from which Marcel recoiled: gales of fresh air, blinding sunlight, shutters and windows thrown open to admit both. Marcel waited until his father was safely entombed at Pere Lachaise cemetery before lining his study with cork and fitting impenetrably heavy curtains, so that his immense act of sensory and cerebral recollection, the visions, inhalations and dialogues, would become illuminated in the gloom, like radiantly focused images thrown on a darkened wall by a camera obscura.

________________________

From Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations by Simon Schama. Copyright © 2023. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Simon Schama

Simon Schama is University Professor of Art History and History at Columbia University in New York. His award-winning books include Scribble, Scribble, Scribble; The American Future: A History; National Book Critics Circle Award winner Rough Crossings; The Power of Art; The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age; Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution; Dead Certainties (Unwarranted Speculations); Landscape and Memory; Rembrandt's Eyes; and the History of Britain trilogy. He has written and presented forty television documentary films for the BBC, PBS, and The History Channel, including the Emmy-winning Power of Art, on subjects that range from John Donne to Tolstoy.