How Acting in True Crime Shows Allowed Me to Write the Story of My Stepsister’s Murder

Rachel Rear on Grappling with Her Family’s Trauma, and Her Own

I zipped up my long black off-the-shoulder velvet gown, covered my anachronistic tattoo with a taffeta shawl, took the coupe glass filled with fake champagne, and stepped out onto the patio of the glorious Bartow Pell Mansion in the Bronx, where a tall, square-jawed, swoon-worthy guy waited to flirt and laugh with me. As the camera began to roll, I felt glamorous, glowing, and energized.

It was easy to forget, in that gorgeous place with sun-drenched rooms and spiral staircases, dark wood, and luxe fabrics, that we were recreating a tragedy—the true story of the 1955 death of Billy Woodward, a Long Island socialite who was shot and killed by his wife, Ann. In this episode of Investigation Discovery’s A Crime to Remember, Ann and Billy attend a dinner party that my character hosts, with the duchess of Windsor as a guest. Later that evening, Ann, perhaps groggy from a mix of alcohol and sleeping pills, shoots her husband in the middle of the night with a double-barrel 12-gauge shotgun, afterward claiming to have believed he was an intruder in their home.

The dazzle of the costumes and the thrill of the camera distracted me throughout that day. But every so often, I would remember: this is about a man who may have been murdered.

I had perhaps an unusual take on stories about murder. My stepsister Stephanie—a violinist and music teacher, whom I had never met—was murdered in 1991. She was missing for seven years before her bones were found in a remote roadside creek by two little boys. The kinship I felt to her and her story only intensified over the years; as her case faded out of the minds of police and locals in the upstate New York town of Greece where she had lived, I found myself unable to shake her loose.

In 2003, a boyfriend with whom I’d been living in Brooklyn went missing after a psychotic break. When I realized he wasn’t coming back from his solo camping trip, I searched his face in old photos for clues. I hacked into his email accounts and his voicemail, trying to find something, anything, that would help me zero in on his location in the universe. I vacillated between all-consuming panic, uncontrollable weeping, hours of catatonic numbness close to sleep, and cool, level-headed detective work. I called his family, his friends, his co-workers, talked to cops at the 78th precinct, emailed photos of him with our dog everywhere. It was six weeks before he finally called me from a psychiatric hospital in California.

Since 1998, I had known that Stephanie had been murdered. But the whole time my boyfriend was nowhere to be found, I thought of the seven long years she had been missing, my stepfather Jerry, my stepsister Melanie, and all the other people who awaited her return. The courage and fortitude it must have taken to exist in that limbo for seven years—it astounded me.

Maybe I was using true crime acting as a slow re-introduction to the very things that most terrified me; it was a way of hitting reset on how I approached Stephanie’s story so that I could tell it at all.

In 2009, the same year that, unbeknownst to me, two detectives were assigned to her cold case, I started to write about Stephanie. In some sections, I even started to write as Stephanie, as though she were speaking from beyond the grave. Writing about her, though, meant returning to that state of perpetual anxiety that must have existed in the years when she was missing. I took in the stories of others: I spiraled down the Internet clicking on names of other missing women, whether they’d been found murdered or were still missing. Maura Murray. Brianna Maitland. Patty Scoville.

The women I was reading about all tended to resemble me: in their twenties or thirties, mostly dark-haired and Caucasian, described as lively, full of life, vivacious, or some other word bursting with vitality. There’s a kind of wish in the choice of vocabulary, as if the words themselves will find their way like a spell to the missing woman and imbue her with life again.

I began, also, to notice the similarities between myself and Stephanie. Like me, she was a teacher and a musician and suffered from debilitating depression. (Jerry would also, sometimes, mistakenly call me by his murdered daughter’s name.) Much later, I would learn even more about Stephanie’s history with abuse, which also mirrored mine.

I didn’t have a lot of control over the abusive household in which I grew up. I didn’t feel protected by my father; I felt endangered. As I began to write Stephanie’s story, I sometimes wondered if my childhood fears, terrors that made me jump at every sound in the house, that kept me from sleep even before my adolescence, the same fears I was forcing myself to face in order to write about my stepsister, were manifestations of my rage at being unable to change my circumstances.

I was very afraid of whatever had happened to Stephanie. All we knew for sure was that she’d been murdered—by a man, most of us assumed.

The summer I began writing her story, I spent a lot of time at my mother’s house, writing while she visited Jerry in hospice. Once, after spending the morning reading about Maura Murray, I headed out for a walk with my dog. I walked on Route 9, flocked by pine barrens. The air smelled like sweet hay and childhood county fairs. About a half mile from the house, the first vehicle honked, two burly guys on motorcycles. It startled me for a moment, and I counted four more honks before I reached my destination. The possibility of abduction and violation were in every shadow, every situation; any car that drove by could stop and force me inside. My dog, pit bull though he was, didn’t stand a chance against firearms. I could imagine it: coercion, abduction, rape, murder, body suddenly dumped in a gravel pit in the pineland.

I began to doubt my process of research into Stephanie’s murder. Why was I allowing my mind to venture into these dark spaces? Were all those hours poring over witness statements, newspaper articles, police reports, psychic readings, worth it? I wrote thirty pages and felt stuck. Meanwhile, I began dating someone who encouraged me to take acting more seriously—and I started getting cast in projects, which drew my creative attention away from the dark pursuit of Stephanie’s story.

I loved that shoot in the mansion in the Bronx; loved being part of that story, loved learning about the Woodwards and their bizarre socialite world, how Truman Capote himself loathed Ann Woodward and sent her a copy of his unfinished manuscript, Unanswered Prayers, in which he’d modeled a gold-digging character after Ann herself, how Ann had died by ingesting cyanide after reading Capote’s work, how Ann and Billy’s two sons, James and William, both died by suicide in the decades following. I loved being able to bring that story to life: the story of a cursed family wrapped up in money and secrets, a shooting death that may have been a murder.

I began to seek out other roles on Investigation Discovery. At the same time, the friction between the kitsch of the re-enactments and the reality we were portraying continued to press on me. I kept thinking about Stephanie; I had abandoned the story of her murder but had found myself in show after show about the murders of other people.

Eventually, I turned back to my writing. I realized, in retrospect, that part of the reason I had jumped headlong into a contrived, sudden acting “career” was to avoid the dark places I had shied away from in 2009. I began to think that when we hear about a life cut short, we seek to make meaning of it, and if memorializing a murder victim by unflinchingly, honestly telling their story can offer an audience any glint of understanding of this chaotic, dangerous world, I believe it is a story of value. To tell Stephanie’s story, I would have to grapple with my own history of depression and abuse—with my deepest fears of assault, violation, and powerlessness.

Maybe I was using true crime acting as a slow re-introduction to the very things that most terrified me; it was a way of hitting reset on how I approached Stephanie’s story so that I could tell it at all. When I was 14, before my mom had even married Stephanie’s dad, I clung to her story like it was my own, like I sensed in some way that what happened to her could happen to me. And when I took her story back up in my thirties, I felt I was reclaiming our youths for us both. If I could make sense of Stephanie’s senseless murder, perhaps I could make sense of even more.

______________________________________________

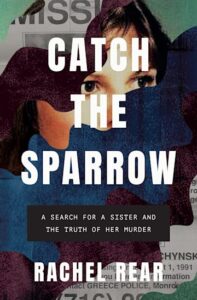

Rachel Rear’s Catch the Sparrow is available now via Bloomsbury.

Rachel Rear

Rachel Rear is a writer, teacher, actor and sometime aerialist living in Brooklyn, NY. She earned her BA at Rutgers University, her MA at Teachers College, Columbia University, and her MFA at The New School. She has been published in the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, the Huffington Post, Crab Creek Review, Off The Coast Poetry Journal and Ducts Webzine. She also hangs around Circus Warehouse in Queens, NY. Her first book is CATCH THE SPARROW, a true crime/memoir.