How Abolition Feminism Fuels the Movement For Black Liberation

Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie on Black Feminists' Fight Against the Carceral State

In July 2015, Andrea and Mariame participated in the founding conference of the Movement for Black Lives in Cleveland, Ohio. Over 2,000 Black people from across the United States and Canada gathered to discuss state violence, strategize about effective organizing, and simply be together a year into the Ferguson Uprising. Both of us facilitated workshops on police violence and criminalization targeting Black women, trans and gender nonconforming people at the convening. After two days of conversation, strategizing, and community-building, we were both getting ready to head home, which, for both of us, was Chicago at that time, where Mariame had lived since 1995 and Andrea had relocated in 2014.

Mariame had traveled to Cleveland on a bus with a group of young Black organizers affiliated with BYP100, a youth-led organization with chapters across the U.S. As she walked back to the bus with fellow organizers, they encountered a group of people demanding that the police release a twelve- or thirteen-year-old Black boy who was sitting in a bus shelter in handcuffs. Andrea was already on the scene, having run over as soon as she saw a small group of conference participants gathered around the cop cars as she was leaving the conference. Dozens of Black people who had just come together to chart the future of a post-Ferguson Black liberation movement surrounded the bus shelter. A comrade successfully reached the boy’s mother on the phone. It was clear that no one was going to leave until she arrived, and the boy was safe.

The cops escalated the standoff when they tried to move the boy towards one of the police cars parked in the street. The steadily growing crowd followed, shouting at the cops to release the boy, telling them that his mother was on her way. Meanwhile, more and more Black people were pouring out of the surrounding buildings from the conference and making their way to the scene.

Black feminism offers a vision for liberation not just for Black women, but for our entire community, and for all who experience oppression.

Suddenly, one cop began indiscriminately spraying the crowd with pepper spray. A couple of other cops joined in, and chaos broke out. The cops didn’t care who they were spraying. We were all Black and it didn’t matter if we were women, men, gender nonconforming, trans, adult, elder or child. They sprayed us, as our friend and organizer Page May said, “like we were bugs.”

Malik Alim, a young organizer from BYP100, who Mariame knew and who tragically passed away in August 2021, narrated his personal experience of the incident:

I’d never been maced or pepper sprayed before and the moment between realization and sensation felt like a lifetime, like waiting for the pain receptors to fire after stubbing your toe. I stumbled out of the street and into the grass where a woman from the group I traveled with, we’ll call her C, caught me in her arms. I was blinded, but I could hear people screaming. I added my own voice to the ruckus, pleading for water to rinse the poison from my eyes. Almost immediately, I began to discern some of the yelling voices warning against the use of water and urging able bodies to run to the nearby grocery store for milk. We needed to pour milk into our eyes, to neutralize the poison. As I writhed on the ground in agony, I remember I was wearing contact lenses. I begged C to help me remove them and quickly regretted it. As soon as air hit my pupils, the pain intensified. As I screamed, C quickly explained to me that she was still nursing her young daughter and that she could deliver milk more quickly than the store runners if I let her. I quickly obliged and she administered the cooling substance directly from her breast. I was already crying, but her selfless act of care for me, her fallen comrade, unleashed a reservoir of emotion from deep within me.

When Mariame heard the screams and saw some people falling to the ground, she ran towards the 7-11 that was about a block away to purchase milk. When she returned, she noticed that more cops had arrived and that the boy had been moved from the bus shelter into a cop car. The crowd encircled the car to prevent it from moving. Andrea—who had earlier been shoved to the ground by a cop as she and others yelled at police to put away the pepper spray and the TASERs some were starting to unholster—was now huddled with a small group of Black women movement lawyers, negotiating with police to try to stop them from arresting and charging the boy—or anyone else. We were all trying to prevent them from further escalating what was becoming an increasingly tense and dangerous situation. Finally, the boy’s mother arrived, and he was released into her custody without charge.

We accomplished our goal: we successfully prevented yet another Black child from being dragged into the maw of the criminal punishment system that day. We did battle where we were standing, with those we were standing with. We put the liberation dreams we had been envisioning and sharpening together over three days at the convening into practice. We insisted that whatever reason cops claimed as justification to cuff and cage a child—failure to pay a transit fare, underage drinking, refusing to get off the bus or comply with their commands, being young and Black—we weren’t having it. We won that day when the police returned the boy to his mother. And when we knew we had won, the group broke out into spontaneous cheering and dancing as someone began to chant: “We Gon’ Be Alright, We Gon’ Be Alright,” echoing the lyrics of the Kendrick Lamar song that had rung out the first night of the convening.

“Nobody’s free until everybody’s free”

–Fannie Lou Hamer

*

The incident in Cleveland was a stark reminder to everyone present that all Black people are targets for the violence of the state, and that it will take bold collective action for all of us to get free. As we left a gathering focused on Black liberation, we refused to settle for visions of freedom that did not include a criminalized Black child, his Black mother, and everyone targeted for police violence that day.

We engaged in active collective resistance to the violence of policing, we practiced mutual aid and collective care, we refused to allow a mother to be separated from her child by the state, and we demanded a vision of safety that doesn’t put children—or anyone—in cages. All of us were needed. All of us had a role to play. All of us were valued. We left nobody behind. We lived into freedom fighter Fannie Lou Hamer’s mandate that none of are free until all of us are free—including everybody in cuffs and cages of any kind.

We recognize the carceral state as the central organizer of racialized gender violence and a primary site and source of unfreedom for Black women.

While initially the target of police action was a Black boy, we recognized, responded to, and resisted all forms of violence against all Black people the incident involved. And we were led, in large part, by Black women, queer and trans people. Our collective response represented Black feminism in action: Black feminism offers a vision for liberation not just for Black women, but for our entire community, and for all who experience oppression.

We are Black feminist abolitionists. This means we are shaped by Black feminism and abolition feminism—and their intersections. As legendary Black feminist scholar and activist Barbara Smith once stated: “Feminism is the political theory and practice to free all women… Anything less than this is not feminism.” For us, the freedom feminism demands extends to freedom from all forms of violence, including surveillance, policing, punishment, borders, and war. In other words, as the authors of Abolition. Feminism. Now. simply state, feminism must be abolitionist, and abolition must be feminist.

Black feminism—from which abolition feminism emerges—is rooted in Black women’s lived experiences, in which the violence of the carceral state plays a central role. As Black feminist historian Sarah Haley describes, “the very possibility of black subjects’ claim to womanhood was a perceived threat to white supremacy and the carceral state was a key mechanism to crush such a possibility.”

Black trans feminist scholar and abolitionist Che Gossett elaborates that, “The violent figuration of Black people as criminals, thugs and brutal animals… is also sexualized and gendered against Black trans, queer, and gender nonconforming people… Black queer and trans feminism deepens our analysis of gendered experiences of anti-Blackness to understand how Blackness is policed and punished as inherently queer and trans; disability justice illuminates the ways in which Black people are policed and punished as inherently disabled. Because Black feminism is concerned about violence in all its forms, wherever it takes place, it must be anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist.

And, because Black women, queer and trans people thus exist at what INCITE! describes as the “dangerous intersections of multiple forms of oppression,” in the words of the Combahee River Collective Smith co-founded, “our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” This is the basis of the declaration that if Black women, trans, and gender nonconforming people are free, then everyone is free. Abolition is essential to achieving its vision.

We came to abolition guided, and deeply informed, by Black feminist theory and practice. Contemporary Black feminists scholars and organizers like Smith, Angela Y. Davis, Beth E. Richie, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Kai Lumumba Barrow, Rachel Herzing, Tourmaline, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Kenyon Farrow, Barbara Ransby, and Che Gossett, along with Black feminist leadership of abolitionist organizations like INCITE! have been our touchstones.

Hidden histories of Black feminist organizing against the violence of the state, including that of enslaved women resisting criminalization for acting in defense of themselves, Black women in the civil rights movement organizing against police sexual violence, and the multi-movement campaign to free Joan Little after she killed a cop who sexually assaulted her in self-defense, have all deeply shaped our work. We have learned from Black feminist leaders of anti-colonial and anti-apartheid struggles, and from Black feminists fighting ongoing imperialism, globalization, and climate injustice around the world.

Abolition feminism thus enables us to expand the scope of our abolitionist politics to include all arenas in which carcerality operates.

We, in turn, have infused Black abolition feminism in our organizing and advocacy—including into the Vision for Black Lives that emerged from the 2015 founding meeting of M4BL, which both of us contributed to writing, updating, expanding, and deepening to more clearly center Black queer and trans feminism, disability justice, and migrant justice in its demands. Both of us have worked for three decades to bring Black feminist analysis to conversations and organizing around policing, criminalization, and safety.

This work has taught us that when we center Black women, queer, and trans people’s experiences, we gain a more expansive view of the multiple forms and contexts of policing, a deeper understanding of how far policing reaches into institutions of the carceral state, and a clearer picture of how it manifests in our communities. By rooting our analysis in the lived experiences of Black women, queer and trans people, we recognize the carceral state as the central organizer of racialized gender violence and a primary site and source of unfreedom for Black women.

Abolition feminism and “Black queer and trans and feminist thought provide an arsenal of critique and praxis that allows us to think rigorously…about violence,” illuminating how surveillance, policing, and punishment operate along multiple axes of race, gender identity and expression, class, disability, and nation, in multiple settings—home, community, and engagement with the carceral state.

Abolition feminism thus enables us to expand the scope of our abolitionist politics to include all arenas in which carcerality operates—including the policing of motherhood, access to care, sexuality and the sex trade, and the family regulation system. It allows us to see the roots of the carceral state in efforts to control Black women’s economic, reproductive, and sexual autonomy in the wake of the legal elimination of slavery. It helps us to understand how the violence of organized abandonment, reflected in staggering rates of poverty, employment discrimination, denial of labor protections, and environmental racism renders Black women, queer, and trans people more vulnerable to interpersonal and community violence, as well as to the violence inherent in policing, criminalization and punishment. It points us definitively toward what must be done: as Black feminist scholar Saidiya Hartman puts it, “Incredible vulnerability to violence and to abuse [that] is so definitive of the lives of Black femmes…requires abolition, the abolition of the carceral world, the abolition of capitalism. What is required is a remaking of the social order, and nothing short of that is going to make a difference.

Abolition feminism also offers a vision of a world free from all of these forms of violence. As Black feminist abolitionists, we reject the violence of the carceral state in service of racial capitalism; instead, we practice and fight for conditions that will create safer communities and bring us closer to liberation. We understand that carcerality does not attend to the root causes of violence or other social problems.

Rather, it simply disposes of those individuals that represent these “problems” while leaving underlying conditions of violence untouched. Abolition feminism, in contrast, advances a radical approach to violence—“getting down to and understanding the root cause,” as Ella Baker urges us to—by creating new forms of governance and structures based on support, accountability, and care rather than violence, domination, and control, new economies based on abundance and prioritizing meeting the needs of all rather than on capitalist logics of scarcity, competition, individualism, profit-making, extraction, and exploitation.

Abolition feminism acknowledges that no future will be completely free of harm. However, it does hold that it is possible to build systems and structures that address harm in a manner that facilitates healing and transformation rather than a continuing cycle of harm and punishment.

___________________________________

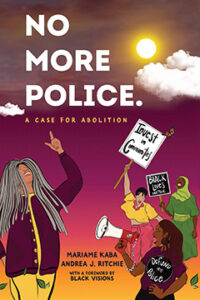

Excerpted from No More Police: A Case for Abolition by Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Richie. Copyright © 2022. Available from The New Press.

Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie

Mariame Kaba is a leading prison and police abolitionist. She is the founder and director of Project NIA and the co-founder of Interrupting Criminalization. She is the author of the New York Times bestselling We Do This ’Til We Free Us and co-author (with Andrea J. Ritchie) of No More Police (The New Press) and lives in New York City.

Andrea J. Ritchie is a nationally recognized expert on policing and criminalization, and supports organizers across the country working to build safer communities. She is co-founder of Interrupting Criminalization, the author of Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color, and the co-author (with Mariame Kaba) of No More Police (The New Press). She lives in Detroit.