How a Venetian Monk Created the First Annotated Map of the World

Meredith F. Small on the Textual Cartography of Fra Mauro

Medieval mappamundi have been called the encyclopedias of their age. The idea that a map can be a book of knowledge comes not from the drawings of landmasses and oceans, but from the fount of information and the geography on these maps. Fra Mauro’s map is the best example of such a cartographically based encyclopedia not only because of its orientation and expanded view of the world but also because it is so thoroughly referenced.

The map seems to have scribbles all over it, but those scribbles point to Fra Mauro’s thinking about where he placed landmasses, cities, rivers, and people. Overall, it’s hard to imagine a map more textually explained than this one.

Until the Renaissance, most cartographers traditionally allowed their maps to stand without many words beyond place names and topographical features, but that style was not enough for this monk. He had amassed a great amount of geographical and cultural information and then wanted to translate all that onto a limited surface, somehow to superimpose all that knowledge in a way that was consumable by the viewer. And so, he chose to do that with words.

Presumably, Fra Mauro realized that maps were interpretive documents subject to the whims of the cartographer, and so it looks like he wanted to tell the viewer not only what they were looking at, but why he chose the positioning and representations that he did. The inscriptions act as bibliographical sources, giving credence to his decisions. At every line, we know what Fra Mauro knew, where he got his information, and sometimes why he chose one position over another.

These texts make the map much more of an encyclopedia than a geographical representation.In general, these inscriptions act as references since Fra Mauro cites who told him the information or where he read it. And so, these texts make the map much more of an encyclopedia than a geographical representation. They also make this map the first concrete step toward scientific mapmaking, a process that relies more on direct observation supported by several in-person accounts rather than stories handed down through generations.

As Fra Mauro’s map pushed mapmaking forward into a scientific process, it was also the cultural Rosetta Stone between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Specifically, Fra Mauro took issue with many established traditions that had carried on from classical times. For example, on the map, he textually questioned why Ptolemy had no knowledge of the Black Sea and pointed out that the classical Greek cartographer knew nothing about northern China or Persia.

But, as historian Piero Falchetta explains, Mauro was, in general, following Ptolemy’s dictate that geographic knowledge changes over time, and therefore we must expect maps to change. That, too, is a modern scientific approach—perspectives change as knowledge accumulates. Fra Mauro subjected every inch of this map to critical and extensive evaluation; in the inscriptions, we see how his mind worked, and how important it was for him to substantiate his decisions. Even now, the map is a running dialogue between the cartographer and the viewer; he is endlessly explaining how he came to put down a name, topographical feature, or whatever it might be on a particular place on the map.

There are more than 3,000 notes and place names, amounting to 115,000 characters, which is surely more inscriptions than any map that came before or after this one. There are 2,500 toponyms for provinces, cities, watercourses, mountain ridges, and such. On top of those names, there are 300 legends, that is, paragraphs or short bits that are teaching moments written in the third person that give textual support for Fra Mauro’s decisions. Unusually, 34 legends are written in first person, and 80 of them use the pronoun Io, which means I in Veneziano and Italian.

Reading these legends feel as if he were standing there talking to the viewer. Those remarks vary in length, from the several long cosmological notes and twenty-eight short notes that begin with “nota che,” or “take note,” as a heads-up. There are also some special inscriptions, words on cartouches, which are illustrations meant to look like scrolls that make these legends stand out as important, and many of those are written in first person as well. Some of these remarks have been taken from various manuscripts, often classical ones written by others, and he usually gives the original author credit.

To cartographic historian Angelo Cattaneo, these notes seem to “often be used in an adversative sense with respect to other authors that the Camaldolese friar was criticizing, correcting, and contradicting.” Cattaneo also suggests these confronting notes are sometimes aimed at the current viewer of the map, as if the cartographer and viewer were in an ongoing discussion or argument. In that sense, they are interactive rather than simple explanations. By that mode of discussion, Fra Mauro elevates the discourse and places himself in the position of an authority.

At the same time, he is asking the viewer to evaluate his texts and decide for themselves, especially when he presents contradictory information compared with other authorities. He is using this map as a learning experience for his audience. “In this sense,” Cattaneo writes, “The mappamundi is among the first texts in which the readers are made aware of the critical choices made by the author during the composition of the work.”

But often, Fra Mauro also humbles or excuses himself with words: “Though I have been most diligent in trying to put all the coastlines of this sea [the Mediterranean] in accordance with the most accurate map that I possess, those who are experts should not take it amiss if I am not always consistent. Because it is not possible to put everything accurately.” Here we have Fra Mauro talking directly to us, airing his feelings about how hard it is to make cartographic decisions, especially ones that might not be accepted or appreciated by those in the know, and then leaving us to decide whether we accept his logic or not. The map itself is a record of the information he gathered and how he thought through the material as he decided to use, alter, or omit some piece of acquired or traditional knowledge.

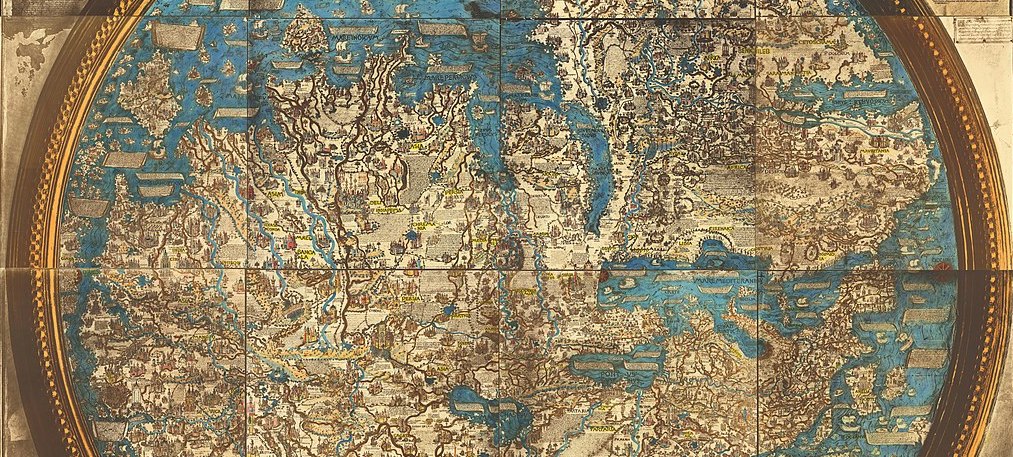

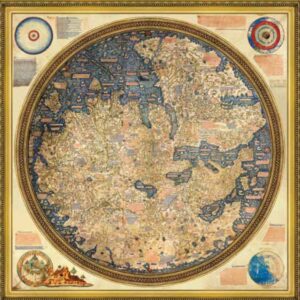

Fra Mauro’s Mappamundi, 1460, Venice, Italy.

Fra Mauro’s Mappamundi, 1460, Venice, Italy.

These inscriptions also say much about Fra Mauro, Venice, Europe, and the cultural world in which he was working. Like all maps, the Fra Mauro map is an artifact of its time. The original texts pin, for medieval times, what geographers and explorers knew as fact and what was much more vague or unknown. But this map also honors the dynamic history of mapmaking that encourages constant change in the knowledge of geography as well as points of view interpreting that geography. Fra Mauro was doing his best as an academic during this period leading up to the Scientific Revolution to dissect and reference every decision he had made about every single mark on the vellum.

The verbiage on this particular mappamundi is also done in a conversational, homey, style. If all the inscriptions, the scrolls with long texts, the notes by cities and rivers, and the comments about the cosmos, could speak, this map would be a cacophony of voices, a veritable blizzard of words. The overarching choice to add all those texts, to note every bit of geography, was perhaps Fra Mauro’s most significant choice. He could have set those words into a manuscript or book and set it alongside the map for those who might be interested in how he arrived at this or that feature.

Instead, he chose to clutter the map with all those words. That choice was revolutionary and effective, and one of the main reasons this map is so important in the history of mapmaking and the history of how humans perceive their world. It should also be noted that in contrast to all those words, there are no human figures anywhere except in the Garden of Eden, which is outside the map.

Out of the three thousand or so bits of writing, most of them relate to place names, but about two hundred are, in the words of Fra Mauro historian Angelo Cattaneo, “A grand treatise of cosmography including descriptions of places and people, commercial geography, history, navigation, and expansion, and, finally, questions that would today be defined as methodological.” Fra Mauro knew exactly what he was doing, and that it would be difficult for the viewer.

On one of the cartouches he wrote, “If someone finds incredible certain of the previously unheard-of things which I have noted above, he should not submit them to the judgment of his own reason but rather list them among the secrets of Nature.” In other words, Fra Mauro knows that some of the viewers would not be intellectual giants, and certainly, most of them were not as educated as he was about geography, so he is also asking for the viewer’s trust. Right on the map, he says the viewer should rely on the experts, such as himself, when they don’t understand something. The reader is essentially being called upon to bear witness to Fra Mauro’s decisions, depictions, and explanations, and this is the first time on any map that a viewer has been enticed into the very process by which a cartographer comes to geographic conclusions.

For example, Fra Mauro explains the rise and fall of the Nile waters just as Pliny does, which means he mixes astronomy and astrology with religious celebrations: “The Nile begins to rise at the first moon after the summer solstice, when the sun is entering Cancer; it swells and overflows in Leo; stops in Virgo and subsides in Libra. That is, between when it begins to rise and then stops and falls, from mid-June to the Feast of the Holy Cross, in September.”

Cattaneo has called this strategy a “kind of theater,” and it’s one where the audience is a participant. And yet, some of these texts are downright defensive. Fra Mauro wrote about his placement of the source of the Nile River, “I think that many will be amazed that here I put the source of the Nile. But certainly, if they approach the question rationally and undertake the same investigations that I have—and with the diligence that I cannot here describe—they will see that here I am undertaking to demonstrate this thanks to the very clear evidence that I have had.”

Or, for all we know, Fra Mauro was a chatty person, and it was natural for him to talk and talk and talk about what he was doing and why. In any case, lucky for us that he made this textual decision. The map would not be as spectacular, or as influential, without those writings. Directly on the map, the cartographer is taking to task previous geographers and philosophers and questioning bits of medieval thought about monsters and myths, all the while seducing readers with words to reconsider previous approaches and ideas.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Here Begins the Dark Sea: Venice, a Medieval Monk, and the Creation of the Most Accurate Map of the World by Meredith F. Small. Copyright © 2023. Published by Pegasus Books.