How a Leading Voice of Eswatini Culture Was Erased From History

Joel Cabrita on Regina Gelana Twala and the Legacy of Racism and Sexism in Southern Africa

Feature image Courtesy of Ohio University Press.

In 2013, I was doing research in the archives of Uppsala University in Sweden. My focus was the papers of Bengt Sundkler, a well-known historian of religion who had done important research into religion in Eswatini, a small country in Southern Africa. I was trying to find out more information about Sundkler’s research materials collected during his time researching Zionism in Eswatini, an indigenous form of Christianity.

As I rifled through Sundkler’s papers—for the most part uncatalogued and unsorted—I made an intriguing discovery. Some of the richest material in Sundkler’s collections of notes, field reports, newspaper cuttings had been sent to him by a researcher named merely as “R.D. Twala.”

This R.D. Twala—whoever they were, man or woman—had sent dozens of typed-out pages to Sundkler in the late 1950s. These pages detailed Twala’s rich findings on Zionist rituals in Eswatini, describing the services Twala had attended, their observations, and their analysis. Twala was clearly highly educated and au fait with methods of social anthropology. Their notes were filled with erudite comments, footnotes, and references to other religious scholarship of the period.

I was surprised that I had never heard of R.D. Twala. As a historian of Eswatini, I had a fairly good sense of the key intellectual figures in the country. It was not at all common to be a Swati intellectual with anthropological training during these years of limited access to universities and further education for Black emaSwati. Yet I had simply never come across R.D. Twala.

I would come to find that obscurity and marginalization were themes that defined Regina Twala’s life and her posthumous legacy,

I quickly did a Google search and found just one reference to R.D. Twala from Eswatini for this period. Twala had run as a candidate in Eswatini’s 1964 Legislative Election, an election held just four years before Eswatini gained independence from Britain, setting the blueprint for the future of the independent country. So not only an intellectual and a trained anthropologist, Twala had clearly also been someone of considerable political stature.

I started asking around my contacts in Eswatini whether anyone had heard of an R.D. Twala who had run in the 1964 election and had been a trained anthropologist. The answer was always the same: a blank stare and a shake of the head. In a country the size of New Jersey, Eswatini was—and still is—a hard place to remain anonymous. Yet, amazingly, this is just what Twala—a politician and intellectual—seemed to have pulled off.

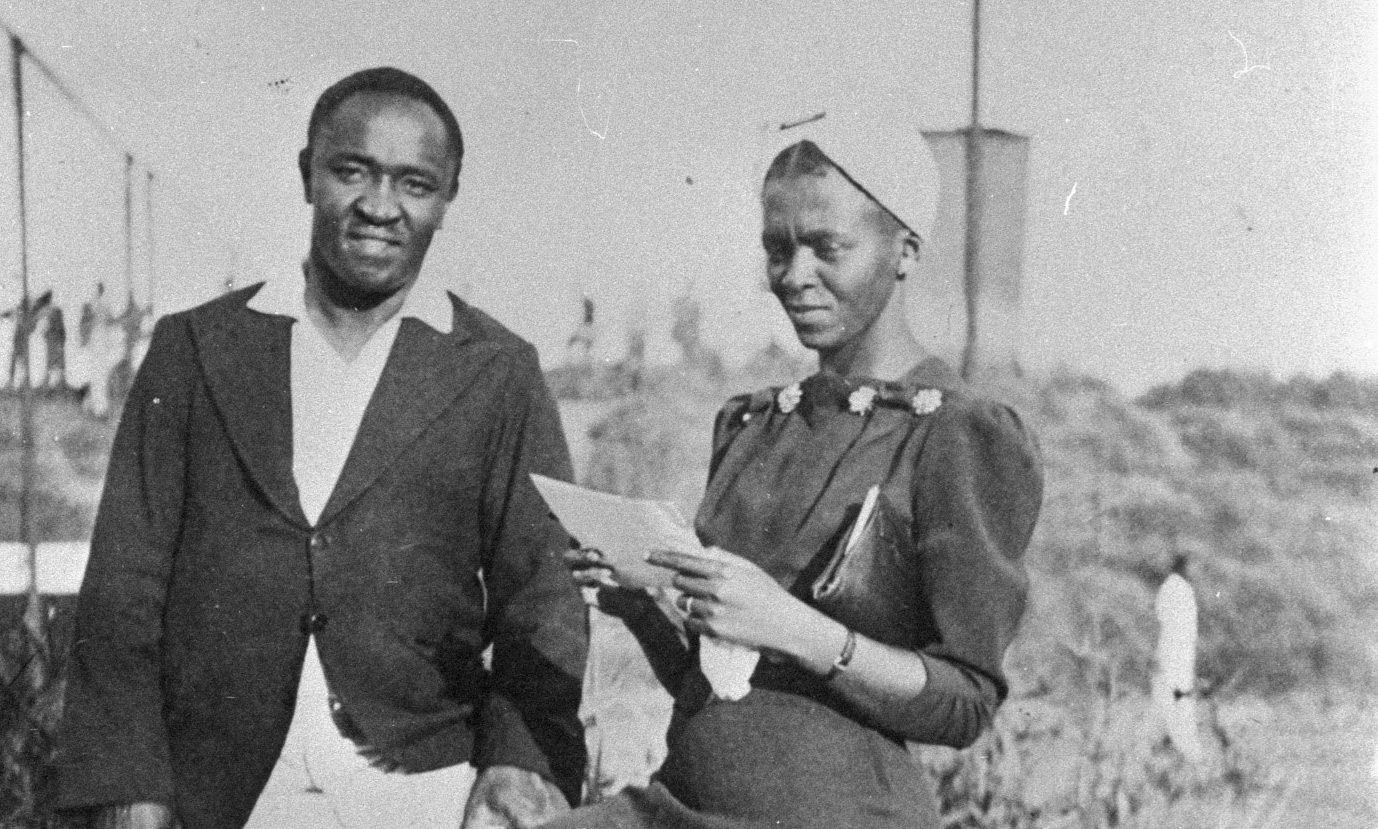

My big breakthrough came just a few weeks later. I found a passing reference to R.D. Twala in a book about the musical scene of Johannesburg in the 1930s. The book discussed Dan Twala, a leading figure in the arts of the city, and a manager of the Bantu Sports Club, a venue that acted as a hub for social and cultural Black life.

A small footnote mentioned the courtship of Dan Twala and R.D. Twala. This was my very first clue that Twala may have been a woman. I immediately contacted the author of the book and had my big breakthrough. The author informed me that a South African historian named Tim Couzens had conducted research on the life of Dan Twala. In doing so, he had consulted many letters that had been exchanged between Dan and his wife, R.D. Twala. I was thrilled. These letters were surely my chance to finally find out more about Twala.

I set about trying to track down these letters. Couzens had died a couple of years ago. I reached out to my networks and was soon put in touch with Couzens’ widow, one Diana Wall, who still lived in their family home in Johannesburg. Diana and I started emailing, and she informed me that yes, there were several boxes—plural!—of letters between the Twalas packed away in her husband’s study. I was welcome to visit.

Opening up those cardboard boxes—untouched for maybe thirty years or so—was one of the most exciting moments of my life as a historian. Inside the boxes, I found hundreds and hundreds of letters—handwritten and typed—exchanged between Dan Twala and his wife, one Regina Doris Twala, over a thirty-year period between 1938 and 1968.

Regina’s personality jumped off the page. Smart, articulate, and opinionated, Twala’s letters to her boyfriend and later her husband were passionate (steamy references to their life between the sheets peppered her missives), angry (Twala raged against the injustices faced by Black people of 1930s Southern Africa), and hopeful (Twala hoped for nothing less than to become a famous writer and intellectual). I immediately realized that this was an epistolary collection unmatched in size, longevity, and quality in African history. I simply know of no other similar collection between a romantic couple.

Courtesy of Ohio University Press.

Courtesy of Ohio University Press.

What I have outlined above were my first faltering steps to find out the identity of R.D. Twala. Rather than my difficulty in finding Twala being a momentary blip, I would come to find that obscurity and marginalization were themes that defined Regina Twala’s life and her posthumous legacy, despite her status and standing during her own time. Twala was an example of a prominent and influential woman who—for reasons I would shortly discover—had been intentionally erased from the historical record. It was no accident that I first worked out Twala’s identity through the life of her far more famous husband, Dan Twala. This was consistently Twala’s fate: for her life to be refracted through the careers and stories of those better known than her.

Twala was born in 1908 in South Africa, just before the Natives Land Act of 1913 was passed, dispossessing Black South Africans of their land and forcing an exodus to towns and cities. She herself followed a similar pattern, moving from rural South Africa to Johannesburg in her 30s to work as a teacher and to live with her first husband, one Percy Khumalo.

Twala’s arrival in the big city of Johannesburg was an education in the challenges faced by Black women of the mid twentieth century. She confronted a hostile municipality administration that sought to clamp down upon independent Black women in the city. As a Black woman who aimed to become a famous writer, Twala was in a category that simply wasn’t legible to white authorities.

Moreover, Twala’s marriage soon fell apart due to Percy’s infidelity. She initiated divorce proceedings—a move that further stigmatized her. Alone and penniless, Twala was forced into domestic service in a wealthy white household—one of the few ways that Black women were able to hang on to a life in Johannesburg.

Twala’s fortunes changed when she met her second husband, Dan Twala, during her time playing tennis at the Bantu Sports Club. Quickly married, Dan and Regina established themselves as one of the power couples of Black Johannesburg, part of the small Black middle class of the day.

Twala resumed her writing career, finishing one manuscript (never published) and working on several others, as well as contributing prolifically to Johannesburg’s newspapers. She soon became part of the pioneering class of the Jan H. Hofmeyr School of Social Work, the first professional school for Black social workers in the country. For many Black elites, social work was a preferred route into politics and public life; Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, future wife of Nelson Mandela, would graduate from the same school a few years later.

Courtesy of Ohio University Press.

Courtesy of Ohio University Press.

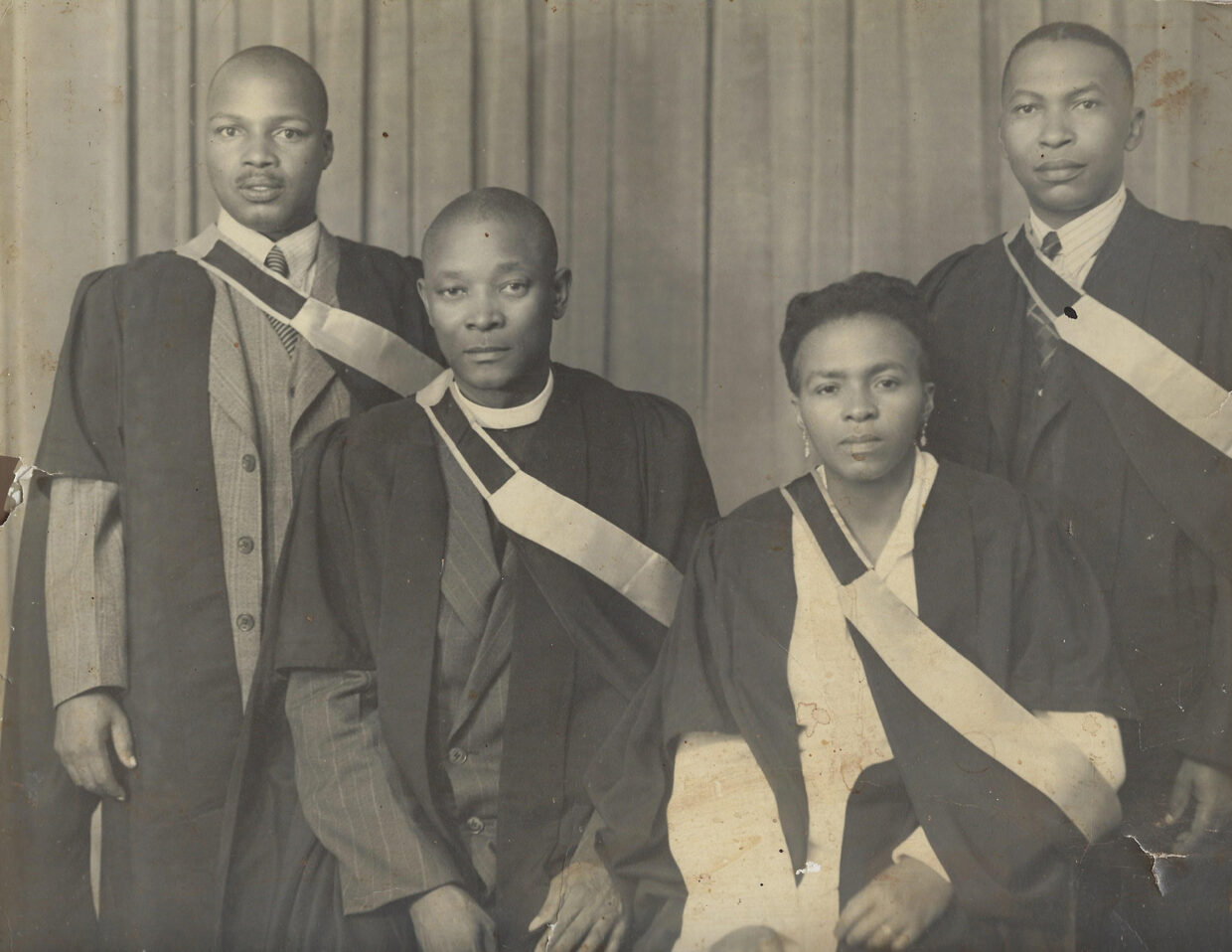

Twala’s upwards trajectory continued. In 1948, Twala would become only the second Black woman to graduate from the prestigious University of Witwatersrand, and the first woman to gain a degree in Social Science in South Africa. She studied under the renowned white anthropologist, Hilda Kuper—a relationship that would continue to exert influence upon Twala even after her death. Twala was part of a tiny group of highly educated Black women in South Africa of the mid twentieth century, overcoming prejudice on account of both her race and her gender.

When the racist all-white Nationalist Party was voted into power in 1948—the event that formally inaugurated the segregationist apartheid government into being—Twala mobilized her privilege and education to become politically active. She joined the African National Congress—the leading opposition party to the racist government—and took part in the 1952 Defiance Campaign, the largest non-violent resistance movement the country had ever seen. Arrested for her participation, Twala spent time in prison and became marked by the apartheid government as a person of interest.

By the mid-1950s, Twala had left South Africa for neighboring Eswatini (her husband, Dan, was from Eswatini). Part of a growing wave of Black exiles from South Africa, Twala realized that were she to stay in South Africa she would surely face imprisonment and perhaps even worse.

This was consistently Twala’s fate: for her life to be refracted through the careers and stories of those better known than her.

Twala’s move to Eswatini was also prompted by growing tensions with her marriage. She was fed up with Dan’s infidelity, and Dan—it turned out—was a man of his times in not being happy with a wife who worked, wrote, campaigned, and in general sought an identity outside of the home. Twala initiated divorce proceedings against Dan (her lawyer was none other than Nelson Mandela), although she ultimately dropped the suit and remained married—but separated—until her death in 1968.

Twala had also just been awarded a prestigious Nuffield Fellowship, a British research award that allowed her to conduct anthropological research on women and culture change in Eswatini. Working under the mentorship of Hilda Kuper (then based at a South African university), Twala started working on an important ethnographic manuscript on cultural change and gender in Eswatini, a career defining work.

Twala’s political career also reached new heights upon her arrival in Eswatini. Eswatini’s monarch, Sobhuza II, was increasing pressure on Britain for independence. Swaziland’s elite Black middle class (in whose company Twala found herself) allied with Sobhuza. The country’s first political party, the Swaziland Progressive Party, was formed by them in 1960.

Twala was a founding member of the Party and its first women’s secretary. She attended pan-African gatherings in Ghana with then-president Kwame Nkrumah. Beyond formal politics, Twala also advocated for women’s education and self-help, starting a crafts organization and single-handedly founding the first library for Black readers in her hometown.

As an anthropologist, Twala was critical of those who weaponized African culture to keep women in their place. Her relationship with Sobhuza soured in the 1960s as she became disillusioned with his suppression of the democratic process. By the mid-1960s, Twala was at the very forefront of those who were campaigning against both the British and Sobhuza’s monopoly over the political process She stood against Sobhuza’s party in the 1964 Legislative Election as well as used her pen for scathing critiques of the powerful and wealthy in Eswatini, mobilizing the press to advocate for ordinary people—most of all women.

But all Twala’s political and literary hopes now came crashing down. In around 1966, she was diagnosed with intestinal cancer.

Twala received treatment in Johannesburg for two years, but it was ultimately unsuccessful. On her deathbed, Twala worked hard to finally try and assure a posthumous legacy. She had failed to publish her earlier manuscripts; Black women writers struggled to gain access to the insider networks that would have made formal publication possible. So, until her death, Twala only found publication in the form of newspapers—a tenuous platform for preserving written work, and one that frequently fades from memory due to the ephemeral nature of periodicals.

Now, on the cusp of dying, Twala was determined that her final opus—her ethnography of Swati women and cultural change—would be published in a more enduring form. She forwarded her manuscript to influential persons close to the King, requesting that the book be published in time for the nation’s independence. Yet the manuscript was blocked from publication by these royal insiders, something that surely points to the fact that Twala had become persona non grata with the powers-that-be.

Twala died in 1968, an early 60. Her funeral was poorly attended without a single representative from the royal family. In life, she had spoken out against the power of the monarchy; in death, she was finally out of the way and there was no reason for them to memorialize her by either publishing her contentious and critical work or by attending her funeral. Eswatini would gain its independence only one month after Twala’s death, but Twala would not be a part of charting the course for the independent nation.

White academics would also close ranks against Twala after her death. Twala’s lone advocate forwarded her manuscript to her former mentor, Hilda Kuper, now professor of Anthropology at UCLA. Yet Kuper declined to assist with publication, declaring the work to be of “no intellectual value”. Kuper and Twala’s initially close relationship had soured as Twala became increasingly critical of white liberal academics and their pretensions to “own” their research sites and subjects.

Kuper had been supportive of Twala her student. She was far less warm to Twala as an equal and potential rival. Twala’s manuscript gathered dust in Kuper’s archives in the US, only discovered by me some 60 years later. Twala’s legacy, the defining work of her career, is enfolded within the papers of her more famous, white, counterpart—a microcosm of Twala’s lifelong struggles to assert herself as a Black female intellectual and literary figure.

A similar pattern repeated itself with the Swedish historian, Bengt Sundkler. As we have seen, in the 1950s Sundkler had hired Twala to do research on his behalf in Eswatini. It was her typed-out research notes in his Uppsala archive that had first alerted me to her existence.

[Twala] was indeed the author of her own life. We are just awaiting this story’s publication.

Yet by the 1970s, with Twala long dead, Sundkler would publish these notes as his own in a blatant act of plagiarism. Twala’s material was passed off as his own by Sundkler in his acclaimed 1976 book, Zulu Zion and some Swazi Zionists. The book established Sundkler’s reputation as a leading scholar of religion in Africa. Twala’s contribution was entirely erased.

This pattern of marginalization has persisted to the present day. The important collection of letters between Twala and her husband, Dan, gathered dust in the private study of a white South African historian for many decades. It is only in the last couple of years that Twala’s descendants even became aware of this collection of letters.

The story moves even closer to home. I myself am also part of this long history of white gatekeeping of Twala, yet another example of access to a Black woman being mediated through a white academic. For all her desire to publish her corpus, the task of telling Twala’s story and of bringing her work to public attention has been taken up by another—and, what’s more, by an academic employed by the kind of well-funded institution at which Regina was never able to find work.

These dynamics are intensely familiar to African Studies as a whole, a field of study historically dominated by white scholars in the northern hemisphere telling the stories of Black Africans. When viewed in this light, it is hard to see my biography of Regina in a straightforwardly rehabilitative sense, to laud it as a worthwhile restoration to memory of an important lost figure.

Instead, my biography begs difficult questions about continued white privilege in telling the stories of Black historical subjects, and of the entrenched power of the universities and presses that have supported my writing career while spurning individuals like Regina Twala.

Yet my hope is that Twala is not an author forever destined to have her story told by everyone except herself, nor that she will be merely remembered via her proximity to those the world privileged more than her. My book offers an account of Twala’s life. I have shone a biographer’s light on aspects of a life that—however important during its own time—has subsequently ended up in dusty boxes and distant memories.

However, the lived experience of that life is Twala’s alone. Her full story—an autobiography of sorts—lives in her hundreds of newspaper articles, her many letters, and her one surviving book manuscript. For Twala wrote of her experiences nearly every day since childhood. And from this perspective, she was indeed the author of her own life. We are just awaiting this story’s publication.

__________________________________

Adapted from Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala by Joel Cabrita, (Athens: Ohio University Press, Copyright © 2023). Reprinted with the permission of Ohio University Press, www.ohioswallow.com. Available from Wits University Press in March 2023.

Joel Cabrita

Joel Cabrita is Susan Ford Dorsey Director of the Center for African Studies and an associate professor of African history at Stanford University and a senior research associate in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Johannesburg. Her work focuses on religion, gender, and the politics of knowledge production in Africa and globally. She is the author of Text and Authority in the South African Nazaretha Church and The People’s Zion: Southern Africa, the United States, and a Transatlantic Faith-Healing Movement.