How a Lawyer, a Businessman, and the Mafia Destroyed Public Transit in the Twin Cities

Jake Berman on the Lost Promise and Possibility of North American Urbanism

There is a common folk theory that the North American streetcar disappeared because of a conspiracy. Allegedly, industrialists connected with the auto and motor bus industries bought up North American streetcar lines, then shut them down to sell more cars and buses.

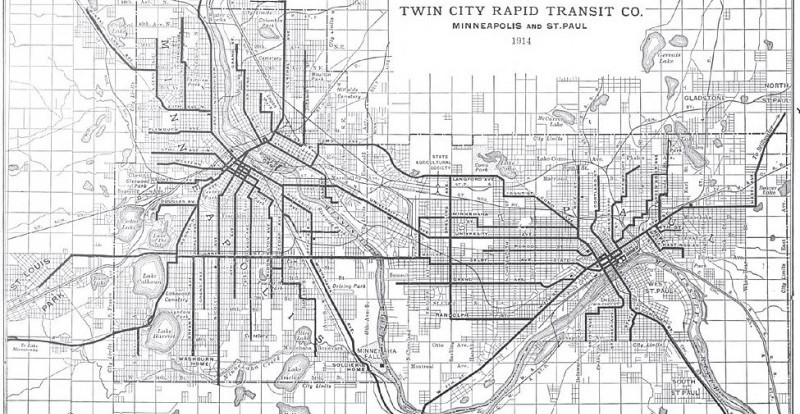

Made famous by the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, the theory has little truth to it. By the 1930s, the for-profit streetcar business was rapidly becoming unprofitable. The industrialists weren’t hawks swooping in on healthy prey—they were vultures picking the bones clean. In fact, there was only one place in North America where a relatively healthy streetcar system fell victim to a conspiracy. That place was the Twin Cities: Minneapolis and St. Paul (fig. 11.1).

The Twin City Rapid Transit Company was a national model for how to run a transit system until a Wall Street financier, a crooked lawyer, and the Minneapolis mob came along and stripped it for parts. High-capacity rail transit wouldn’t return to the Twin Cities until the 21st century.

Fig. 11.1

Fig. 11.1

A Family Business

Twin City Rapid Transit had its origins in the 1886 merger of the Minneapolis Street Railway and St. Paul City Railway. This merger brought nearly all urban transport in the Twin Cities under the control of one company. The first head of the company was Thomas Lowry, the largest real estate developer in the Twin Cities. Lowry used his control over the streetcar system to promote his real estate interests.

Lowry was an enthusiastic civic booster, a founder of Minneapolis’s Library Board, and part of the founding group of the Soo Line Railroad, which still exists today. The Lowry Hill neighborhood, Lowry Park, and Lowry Avenue in greater Minneapolis are all named in his honor. Although Twin City Rapid Transit was publicly traded, the company on the whole remained a family business. Thomas Lowry died in 1909 and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Calvin Goodrich, who ran the company until his death in 1915. Goodrich in turn was succeeded by Thomas Lowry’s son Horace, who ran the company until 1931.

The industrialists weren’t hawks swooping in on healthy prey—they were vultures picking the bones clean.During the Lowry family’s management of Twin City Rapid Transit, the company was an innovator, establishing a reputation for long-term vision and quiet, unflashy management. This included building its own advanced, lightweight, “noiseless” streetcars in-house, which it exported to places like Chicago, Seattle, and Nashville. This culture of competence continued even after the Lowry family no longer managed the company.

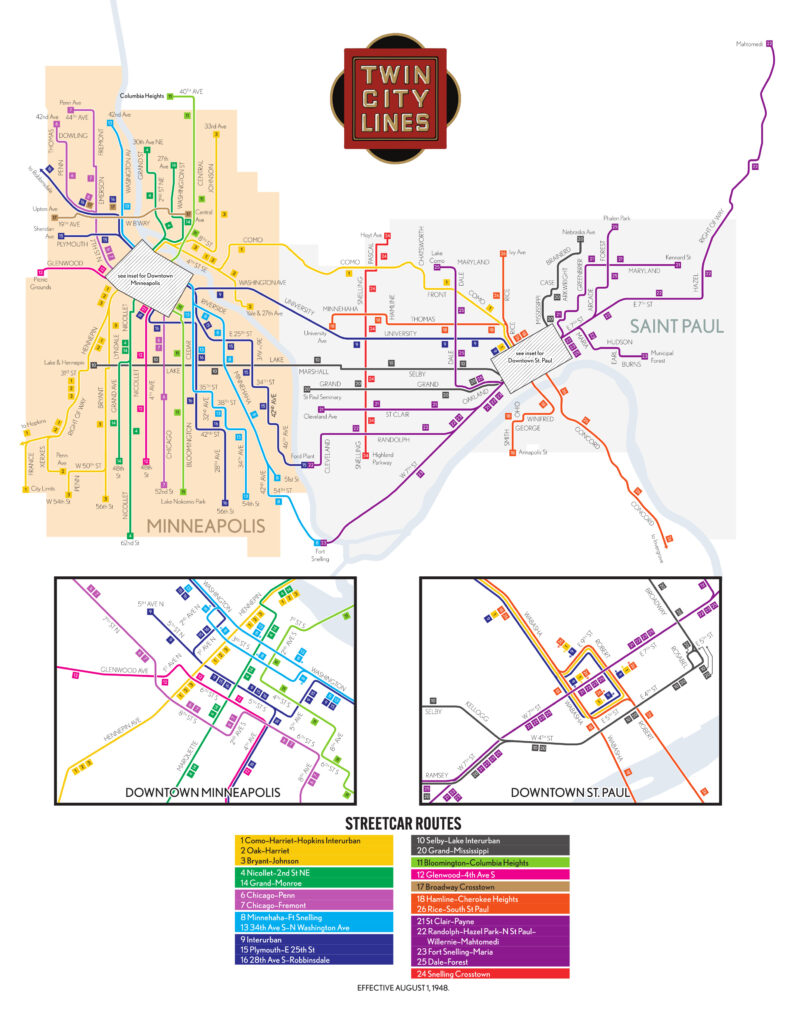

By the 1940s, as the streetcar era was beginning to end, the management of Twin City Rapid Transit continued to take the same long-term view to maintaining a sustainable business. While lightly used streetcar lines were replaced with buses, Twin City Rapid Transit, under company president D. J. Strouse, undertook major investments to modernize the busiest streetcar lines and bought brand-new, state-of-the-art President’s Conference Committee (PCC) streetcars to serve those lines (fig. 11.2).

Fig. 11.2

Fig. 11.2

Sold for Scrap

Strouse’s decision to modernize the core of the streetcar system set events in motion that would ultimately lead to the system’s collapse. In 1948, a New York financier named Charles Green bought 6,000 shares of company stock, expecting a large stock dividend and to make a quick buck. No dividend was forthcoming. Twin City Rapid Transit, to his surprise, was reinvesting revenues back into the streetcar system as it always had. Furious, Green started a hostile takeover attempt. To succeed in this endeavor, Green had to gain the support of other shareholders. One of those shareholders was Isadore Blumenfield, alias Kid Cann, the godfather of the Minneapolis mob.

Kid Cann had gotten his start as a bootlegger during Prohibition, importing industrial alcohol from Canada and selling it in speakeasies. In the 1940s, he still controlled the by then legal liquor trade and had his fingers in all sorts of vice, including labor racketeering, illegal gambling, and prostitution. He was the untouchable king of the Minneapolis underworld. When he was indicted on federal money-laundering charges in Oklahoma, the Minneapolis police chief personally traveled to Oklahoma and testified in Kid Cann’s defense. Kid Cann was acquitted. Arrested twice for murder, he beat the charges both times.

Green and Kid Cann met at the Club Carnival nightclub in 1948 to plot the takeover of Twin City Rapid Transit, and they decided to bring lawyer Fred Ossanna into the scheme. Ossanna was a criminal lawyer, not a specialist in transit law. Ossanna had become wealthy representing the interests of the liquor business, in the process becoming a political fixer for Minnesota’s Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party. Kid Cann was one of Ossanna’s clients.

The triumvirate of Green, Kid Cann, and Ossanna went to war with Strouse and his allies over the course of 1948 and 1949, charging that Strouse’s fiscal prudence was costing shareholders money. Green masterminded a letter-writing campaign to shareholders, contacting each one individually to make his case. This campaign had legs.

When Green went to Minneapolis for the annual Twin City Rapid Transit shareholder meeting in the spring of 1949, he presented an ultimatum to company management: fire Strouse and allow Green to pick half of the board of directors, or else. Strouse rejected the ultimatum, chose to fight, and lost. By late 1949, a majority of the shareholders had been won over to the plotters’ cause. That November, Strouse was out, and Green was in.

As company president, Green brought his brash, pushy New York City style to a state known for its “Minnesota nice.” Ossanna was appointed as the company’s chief lawyer. Green immediately took an ax to Twin City Rapid Transit, promising that all streetcars would be replaced with buses by 1958. He fired 800 workers without explanation. He slashed feeder service to outlying areas, leaving commuters stranded. Maintenance was reduced to the bare minimum.

At the very same time, Green had the audacity to ask the state railroad commission to approve a fare hike. He told the press: “The public be damned! I intend to force a profit out of this company! If necessary, I’ll auction off all the streetcars and buses and sell the rails for scrap iron!” Green acted so aggressively that the state railroad commission had to get a court order stopping him from closing any more lines without the commission’s explicit permission.

Ridership dropped like a brick. Transit ridership was already falling nationwide because of the resumption of civilian auto sales and the end of gas rationing, but Green’s management was running the company into the ground. In 1946, with Strouse in charge, Twin City Rapid Transit carried 201 million passengers.

By 1950, with Green in charge, ridership had dropped to 144 million—a 28 percent decrease. For comparison, New York City subway ridership decreased by 13 percent over the same period. Green’s heavy-handedness didn’t endear him to the people of the Twin Cities, either. Frustrated commuters and their elected representatives made a major political issue out of Green’s ham-fisted cuts. Twin City Rapid Transit became a political target.

One is left to wonder what might have been.The troika of Green, Ossanna, and Kid Cann didn’t last long. Green’s combative style alienated the other two. By May 1950, Ossanna and Kid Cann had turned against Green and stripped him of his power to speak for the company. All official Twin City Rapid Transit pronouncements were to come from Ossanna. By September, Green and his allies on the board of directors had agreed to resign. Green was forced to sell his shares. In the process, he profited $100,000 (over $1 million in 2022 dollars). Through intermediaries, Kid Cann, Ossanna, and other mob associates snapped up Green’s stock, giving them enough shares to control the company outright. The following year, Ossanna became company president.

*

Crime and Punishment

Ossanna, like his predecessor, had little interest in running a competent transit operation. He only accelerated the streetcar shutdown. Ossanna soon signed a sweetheart deal to buy 525 buses from General Motors on credit, and hired a bus expert from Los Angeles to oversee the bus transition. By 1954 the entire streetcar system had closed, four years faster than Green’s original timeline. Twin City Rapid Transit’s modern PCC streetcars were sold to other cities. (Eleven of these PCCs are still in daily use in San Francisco, seven decades later.) The streetcars that Ossanna couldn’t sell were set on fire and sold for scrap metal. Ossanna turned the destruction of the streetcars into a photo op. The newspapers ran pictures of a grinning Ossanna being presented with a check in front of a burning streetcar.

Ossanna and Kid Cann used the system’s closure as an opportunity to corruptly line their pockets. When the duo sold off Twin City Rapid Transit’s streetcar equipment, they sold off company assets at below-market rates and took kickbacks. These dealings defrauded Twin City Rapid Transit out of about $1 million (nearly $10 million in 2022 dollars). A few years later, in 1959, federal agents found out. The feds arrested Ossanna, Kid Cann, and several others on fraud and conspiracy charges. In August 1960, after a four-month trial, the jury found Ossanna guilty. His sentence was four years in prison. The Minnesota Supreme Court promptly stripped Ossanna of his law license.

Kid Cann was acquitted yet again but remained in federal crosshairs. Later that year, prosecutors finally caught up with Kid Cann. He didn’t go to prison for decades of murder, bootlegging, extortion, bribery, fraud, embezzlement, or racketeering, though. Federal prosecutors finally jailed him for transporting a prostitute across state lines. This, and a later jury tampering charge, finally put Kid Cann behind bars.

After the Minneapolis–St. Paul streetcar system closed, Twin Cities transit entered the same death spiral that can be seen all over this book. Mass transit soon faded away as the freeway and the automobile became favored. The regional Metropolitan Council eventually took over Twin City Rapid Transit’s bus system. Attempts to build a subway in the 1960s and a pod-car system in the 1970s never came to anything.

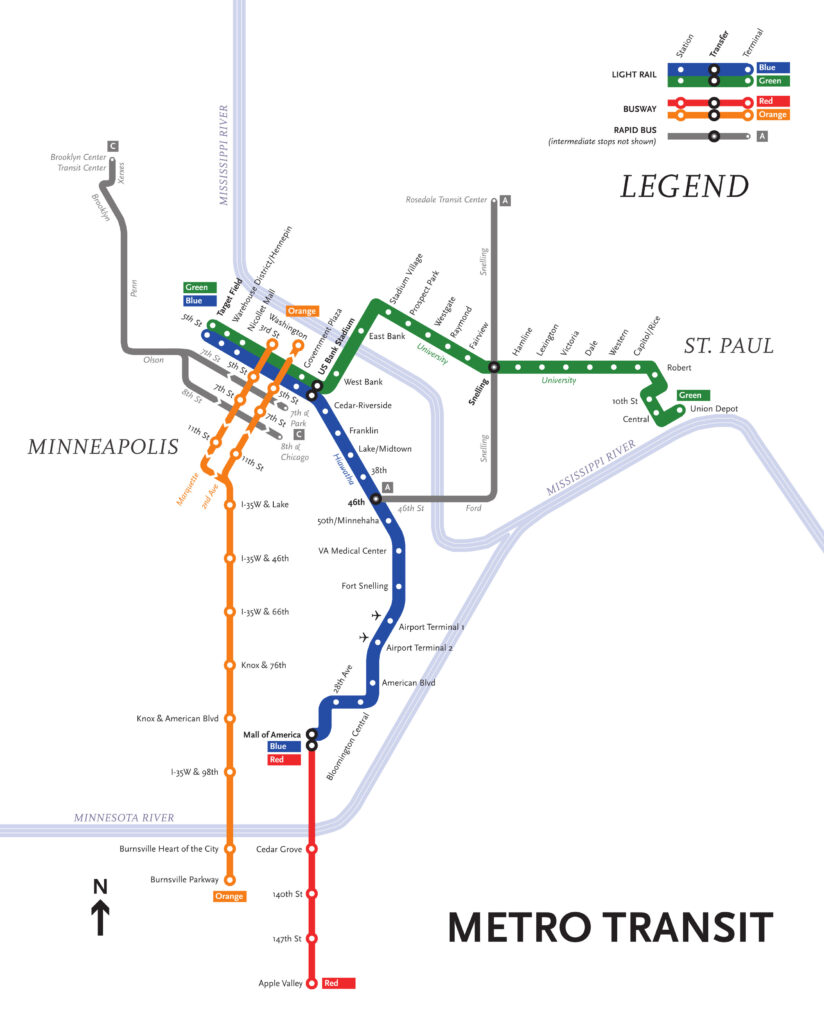

Fig. 11.3

Fig. 11.3

It wasn’t until the 21st century that rapid transit of any kind returned to the Twin Cities (fig. 11.3). The two modern METRO light rail lines operated by the Metropolitan Council run parallel to old Twin City Rapid Transit lines. The Blue Line, which opened in 2004, runs parallel to Twin City Rapid Transit’s old Hiawatha Line. The Green Line, which opened in 2014, follows the same route as the old Twin City Rapid Transit Interurban Line, which ran from 1890 to 1953.

These two light rail lines have proved unexpectedly popular, beating initial ridership projections and creating the political conditions for further expansion. Per mile of track, METRO is notably busier than its contemporaries like Phoenix’s Valley Metro Rail and the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail in New Jersey. This success is due in part to good planning. The Green and Blue Lines both follow busy streets, have major destinations at both ends of the line, and have dedicated lanes so the trains don’t get stuck in traffic.

But none of these modern attempts at rebuilding high-capacity mass transit have the comprehensiveness of the old streetcar system. In the 1940s, Twin City Rapid Transit had the right ideas: replace streetcars with buses on marginal routes but keep the higher-capacity, more comfortable streetcars running on busy routes. This approach prefigured the consensus that developed in favor of light rail in the 1980s. Of course, Minnesotans never got to see how things would’ve played out, because of the meddling of a corporate raider, a crooked lawyer, and the king of the Minneapolis underworld. One is left to wonder what might have been.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from The Lost Subways of North America: A Cartographic Guide to the Past, Present, and What Might Have Been by Jake Berman. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2023. All rights reserved.