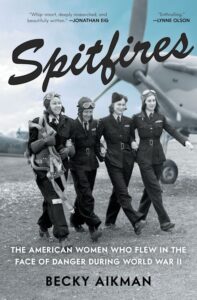

How a Group of Fearless American Women Defied Convention to Defeat the Nazis

Becky Aikman on the “Atta-Girls,” the Pilots Who Chased Adventure During the Second World War

Twenty-five American women were part of a little-known corps that ferried planes for England during World War II. They had crossed the perilous wartime Atlantic in 1942 because the United States military, in all its wisdom, refused to accept women pilots, no matter how courageous and skilled.

Beset by death, blackouts, deprivation, and a perfectly rational fear that Hitler might wipe the nation off the map, the United Kingdom was so desperate for ferry pilots that it accepted some who had lost arms, legs, or eyes. It took pilots who were too old for the Royal Air Force, along with foreigners, members of any race, and yes, even women. Together they formed a civilian offshoot of the RAF that went by the rather pedestrian name of Air Transport Auxiliary. The ragtag flyers of the ATA cooked up nicknames that better suited the arch spirit of the organization: Ancient and Tattered Airmen. Anything To Anywhere. Always Terrified Airwomen. Atta-Girls.

The Atta-Girls got the ride of a lifetime. Joining up was a bold choice, but any woman who had the audacity to learn to fly back when flying was a risky gamble was already breaking a whole string of conventions. The group of young Americans leaped at the chance to fly up to 147 different models of the most advanced aircraft in the world, aircraft like the Hurricane and Spitfire fighters and the Wellington bomber. With little training and even less advance notice, the flyers took on whatever missions were thrown at them each day, often taking command of planes they’d never seen before with only a few minutes to read the instructions.

For women who often had to scratch and beg in their homeland to command single-engine puddle-jumpers made of fabric and wood—or to find any kind of job behind the controls of any kind of plane—this was an opportunity beyond their dreams. It made them the first American women to fly such military aircraft, let alone a whole slew of them, and in a war zone no less.

The Atta-Girls lived ahead of their time, carrying on the way ambitious women aspired to behave decades later.

These pilots had answered a distress call that ricocheted around the world once Germany overran Western Europe by the summer of 1940. Since then, the United Kingdom had stood alone, with only the English Channel, twenty-one miles across at the narrowest point, to provide protection. During the four-month aerial Battle of Britain that year, British pilots in fighters like the Spitfire won the gratitude of the nation for repelling the German Luftwaffe, but the cost was dear. More than 1,500 air crew and 1,700 British aircraft were lost trying to protect the country from German bombs, which killed 43,000 civilians in 1940 and terrorized countless more. Throughout the war, the losses mounted: 70,000 British civilians killed, another 70,000 aircrew dead, and at least 20,000 British aircraft destroyed.

By the time the American women arrived in 1942, the RAF needed ever more aircraft to fend off continued bombing as the country ramped up to take the fight to Germany. Every replacement plane, and every pilot trained to fly one, was precious.

Well paid and well respected for their work, the Atta-Girls lived ahead of their time, carrying on the way ambitious women aspired to behave decades later. Professionally, they mastered jobs that demanded technical expertise, physical strength, steely valor, and quick judgment, all while serving a cause greater than themselves. And privately, the wartime circumstances set them free. Far from home and released from the expectation of settling down in “proper” marriages, they delighted in making their own choices. They pursued their personal lives with gusto, on their own terms. Some kept an eye toward marriage, especially an advantageous one, but others seized the opportunity for same-sex partnerships or brazen out-of-wedlock affairs. For a crazy instant during the chaos and epic change of a world war, they defied every tenet of what was expected of a woman in the 1940s and beyond.

The freethinking, freewheeling Americans also cut an exuberant swath through British society, just as the war was beginning to break down class distinctions and social mores. It made for a fizzy mix. Many British women who served as ferry pilots were daughters of privilege whose wealth had allowed them to indulge the newly fashionable pursuit of winging from ski slopes to garden parties in their own planes. They assumed the Americans enjoyed the same status. And it was true, a few had sprung from the pinnacle of American society. Virginia Farr, twenty-three years old when she joined, was “the flying socialite,” groomed to play the part of a debutante in the family of the Western Union fortune.

Yet Roberta Sandoz, twenty-four, had worked for rock-bottom pay as a crop duster. She scraped together money for flying lessons by performing a mock striptease at an air show, tossing layers of clothing out of the cockpit with each pass over the field. Mary Webb Nicholson, one of the oldest at thirty-six, had bartered for classes by parachuting out of a plane for a publicity stunt without so much as a practice run. And Dorothy Furey grew up in poverty, but she passed in England as a wealthy American heiress at the age of twenty-three by acting imperious and recycling a single red dress.

Someday, the women all knew, if they survived the war, the door to modernity that had opened for them might close again.

Others who made a spirited impression included Hazel Jane Raines, twenty-six, of Macon, Georgia. When she joined up at the age of twenty-five, she aspired to prove that she had the chops to fly for the U.S. military if she would ever be allowed. Helen Richey, thirty-two, was one of the America’s most famous stunt flyers, while Ann Wood was a relative novice at twenty-four. A college graduate, she hoped to parlay wartime contacts into the kind of high-powered career in government or business that was considered out of reach for women at that time. Winnie Pierce, an incorrigible twenty-five-year-old party girl, carried on without regard to caution both on duty and off, while Nancy Miller, twenty-three, a minister’s daughter, lived a squeaky-clean existence on the ground but learned to tear it up in the sky. Mary Zerbel, a twenty-one-year-old romantic, risked her happiness to marry a bomber pilot with long odds of survival. She had been acclaimed in the United States as the youngest American woman flight instructor.

Their former identities didn’t seem to matter. In England, they invented new ones. The brave young flyers were so admired and looked so dazzling in their sharp Savile Row uniforms that lords and ladies invited the Americans to parties, where they shocked the company with boisterous behavior. They danced and drank champagne behind the blackout curtains at Claridge’s and the Savoy as buzz bombs barreled overhead. The international expatriate community that gathered in London couldn’t get enough of the flyers, either. They mixed with a heady scene full of diplomats, journalists, generals, and spies.

By the last year of the war, one third of the twenty-five American Atta-Girls still served. Along the way, others failed to make the grade or lost their nerve. Some married, and several returned home for other work. A few flamed out in crashes that led to injury or death. The stakes were high. Someday, the women all knew, if they survived the war, the door to modernity that had opened for them might close again. They had a few short years to prove themselves, to notch the experience and connections that might allow them to them remain independent and original after the war. To test how far and high they might soar into unknown terrain. Flying without instruments—it was their way of life.

The mission of the American pilots began not in the sky but on ships, rolling across an ocean menaced by German submarines. Adventure beckoned. They were women in flight, and they were going to make the most of it.

__________________________________

From Spitfires: The American Women Who Flew in the Face of Danger During World War II by Becky Aikman, on sale May 6th from Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2025 by Becky Aikman. All rights reserved.

Becky Aikman

Becky Aikman is the author of two books of narrative nonfiction: her memoir, Saturday Night Widows, and Off the Cliff: How the Making of Thelma & Louise Drove Hollywood to the Edge. A former journalist at Newsday, Aikman has written for the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and other publications. She lives in New York.