Every time I woke up, someone died. Usually my girlfriend, Lavender, or my dad, or my boss. Sometimes one of the other assistants. Or strangers I’d seen on the street, unlucky enough to have gotten their faces lodged in my brain, or people I remembered from long ago: the little girl I tutored in college, or Eli McKean. I saw them hacked to bits one by one, or force-fed poison, or tied up together and burnt like witches, their skins blistering over a blazing pyre.

The victims changed, but the murderer was always the same, always me. My hands smeared in gore, eyes alight with frenzied ecstasy. My smile, but wrong, more devious. In my real life, I sat up in bed to rub sleep out of my eyes, I stood in a shower I’d turned hot enough to hurt, I sniffed the armpits of my favorite dress. I kissed Lavender goodbye, or I smiled thinly at my roommates on my way out the door. All while the images poured through me, and I tried to convince myself that they meant nothing, that I didn’t want them. I didn’t want to kill anyone, I thought.

On Halloween evening, Lavender showed up at my office dressed like the night sky, holding a black umbrella, paper stars strung to it with fishing line. I was Donna Tartt in a blazer I’d thrifted on my lunch break—my old bedbug terror had surged like bile; I’d swallowed it down—and a low bun I’d fashioned to look like a bob.

We had initially planned to dress up as Tumblr lesbians, wrapping ourselves in cozy sweaters and twinkle lights. The plan was to spend the whole night entwined. We didn’t mind. We’d been together for ten months, and we were near-telepathic. Often when we were separated, I would feel her heart flutter in my sternum; my palms would get sweaty, and I’d text her to ask what was wrong. Just like she knew when I ate stupidly and drank too much by the nausea curling in her stomach. “Would you stop abusing your body,” she would say, laughing. “For my sake?”

Okay, the truth: I often faked it. Knowing me made her so happy. And she was so often anxious or sad that predicting her moods was nothing more than pattern recognition. Besides, I loved the way our supposed psychic connection lodged us closer together, made our story the stuff of fate, as if we weren’t responsible for our own decisions. Sometimes I thought if I could keep swimming in the current of her love story, I’d never have to make another choice in my life; eventually, I would simply float, thoughtless and free.

For now, fights could take up days, told in three acts, replete with dramatic gestures: we starved ourselves, sobbed for whole mornings, all justified by our status as soulmates. I bragged to friends that it was a more intimate relationship than I’d imagined possible. I was exhausted.

When I added the fourth party to the schedule—a book party, right after work—I asked if we could decouple our costume. I didn’t want to enter the infamous publicity director’s personal home wearing my girlfriend like an ornament, nor to explain wlw meme culture to my bosses and colleagues. Being a twenty-eight-year-old agent’s assistant was already humiliating enough.

I made 26k a year with shitty benefits, my days spent sending endless emails, my nights reading manuscripts on my phone: in coffee shops, waiting for Lavender to get off work, in the bathroom at the bar while she bemoaned nonprofit burnout with her coworkers, on the subway ride home, in bed after she fell asleep and before she woke up. My eyes burned all the time, like visual tinnitus. Lavender kept saying I should get them checked out, but I didn’t have the cash for the copay. If I did, I would start with a gynecologist for the yeast infections I kept getting from wearing the same three pairs of black tights to work every day. After that, I’d see a dentist, once I had the mental wherewithal to handle the questions. It’s from the bulimia, I’d have to practice saying in the mirror first, with a take-me-seriously face. Yes, I know it was stupid. No, I don’t drink soda. I never have. After that, maybe a chiropractor, and then the eye doctor.

“I know,” Lavender would say to my diatribe, settling in behind me on the old mattress my roommates used as a couch, working her thumbs down my spine. “But what if one day you couldn’t read anymore?”

I had forcibly exposed myself to sickening thoughts before—Stare at the word for ten minutes, but no longer, I could hear my therapist saying—but this one was too horrifying to contemplate. Reading had been my truest love since I was a little girl. Growing up, I’d read at dinner, during recess and study hall, at parties, sometimes while hidden in the bathroom or the closet; I’d push my hand against the back wall every time, hoping for a door, for something fantastic and otherworldly to appear and change everything.

In publishing, I’d hoped to find more people like me. I hadn’t been prepared for the social aspect of agenting: the lunches and coffees, or the secret rules of wardrobe and manner. I certainly hadn’t been prepared for my boss, Arthur, with his thrush of gray hair and his stooped walk, like a wizard in a movie. His ancient suits, his eggplant breath. He was a legend in his late eighties. “Don’t worry,” a senior agent had murmured to me once. “He’ll have to retire soon.”

“Or die in his office,” another agent said grimly.

And I had learned not to over-glamorize the reading itself at work—this was author behavior, waxing poetic on speakerphone while we all nodded, bored, in the conference room—and in fact, the older I got, the more starkly I saw that books were not magic and never had been. They were a coping mechanism that allowed me to ignore the outside world when I was small, and then I grew up and decided to turn that coping mechanism into a career. One that I was floundering in but terrified to leave. If I couldn’t succeed at this job, which I’d essentially trained for my whole life, then what else could I do?

Maybe in a different life, I’d have made friends with the other assistants, but they straight-girl flirted with each other with heady desperation, as if finding a work wife was tied to their biological clocks. They clustered, laughing prettily, long-nailed hands stroking backs and shoulders, and I was never good at casually touching other women. I stayed at my desk, only extricating myself on the rare Fridays when Arthur invited everyone to his corner office, made us Manhattans, and regaled us with stories about the good old days in publishing.

__________________________________

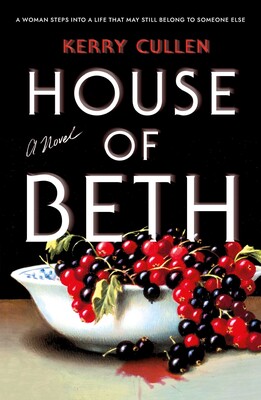

From House of Beth by Kerry Cullen, on sale July 15th from Simon & Schuster LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Kerry Cullen. All rights reserved.