Holding Up Mirrors to the Self: 7 New Poetry Collections to Read This June

David Woo Recommends Saba Keramati, Justin Rovillos Monson, Robert Pinsky, and Others

Poets often talk about poetry in their poems, and what they say can hold a mirror up to reality in a way that blissfully convolutes the folds of a reader’s brain. With a lifetime of honorable service to poetry, Robert Pinsky is a formidable contemplator of poetic paradoxes and influence, writing in his new book, “I want to publish a book with on every page / The one same poem, all not by me but mine.”

With a kind of double-mirror infinitude, the debut poet Saba Keramati employs the cento form, which repeats lines by other poets, and quotes a line by the poet Sarah Gambito: “I’m a poem someone else wrote for me”—in other words, a poet writing a poem that quotes a poem in which another poet declares that she’s a poem written by someone else for her, perhaps the future poet who is quoting her back.

Justin Rovillos Monson, writing from prison, advises using the fragments of one’s experience to remind you how it feels to be alive: “Hell, / light ’em up in a poem to remember / where your body vibrates.” Chris Nealon focuses on that uncertain moment, akin to writing down a dream before you forget it forever, when all that stands between the creation of a poem and its vanishing from your mind is a simple utensil: “Composing a poem in your head and hoping that the organizing thought is sturdy enough to keep the words in order till you lock your bike and grab a pen—”

Once it is on the page, what matters is whether the poem enacts something important in a poet’s life. Tayi Tibble, with youthful ardor, sends out poems as a means of seduction (“I read too many poems / exactly like this one / and sent them over text / like nudes, like ekphrasis / in reverse”), while Heather Treseler cherishes an historical perspective, describing how the friendship between Maxine Kumin and Anne Sexton employed the elements of a suburban American life to make something new: “you and Anne had shared a phone line and desktop conspiracies, / penning poems under the surface realities of married bourgeois women.”

However limited and human it may be, poetry can be a way of touching the sacred. A “green distance” gilding the darkness in Nebraska leads Donald Revell to a near-speechless insight where only poetry is adequate to the globe-bending amplitude of the vision: “In less than a moment, the few / Words ample to all poems bent / Horizon into a Mercator crown.”

*

Saba Keramati, Self-Mythology

The mythology of self that Saba Keramati’s poised debut collection seeks is a vision of completion and moral amplitude in the face of the willful losses imposed by American assimilation. A light touch enlivens the search: “Try to guess: which is the Chinese leg / and which is the Iranian. Hint: / one is hairier than the other.”

When the trinominal speaker—Chinese Iranian American—encounters an idol, the Canadian poet and classicist Anne Carson, she yearns for wisdom: “I lost my languages and so I wanted an explanation: / Where does unbelief begin?” But the poet evanesces in “a trail of wet footprints.”

The search for a self-mythology, it turns out, is like the bildung in any bildungsroman, full of cul-de-sacs, elliptical understandings (“I’m forced to wonder what forgetting means, if I can be reminded so easily”), and even a kind of chorus of charming, judgmental “aunties,” who giggle when she tries “to render each strand of [her]self invisible” upon arriving in veiled Iran. To permit oneself to be assimilated by a trusted loved one is the arduous yet exquisite goal: “the way I disappear into my mother’s long black hair when she bends down to kiss my forehead. I am a part of her again. She is full with me.”

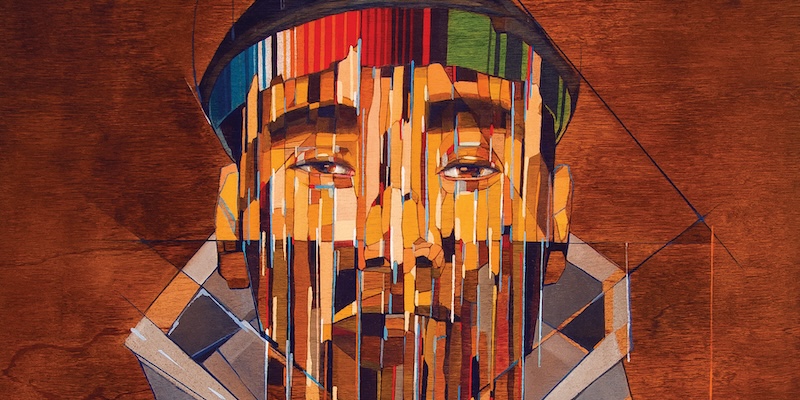

Justin Rovillos Monson, American Inmate

“I made myself / a dumb prophet,” writes Justin Rovillos Monson, “& cuffed my own / wrists like a God who creates / & creates & creates….” Just as artists have traditionally challenged divine order to be the makers of their own earthly creations, so Monson, through crimes he committed as a teenager, enabled the setting that is both the fetters on his freedom and the material for his poetic inspiration, the Michigan correctional facility where he is serving a sentence for armed robbery.

Monson, a thirty-three-year-old Filipino American, creates a sacred and profane mixtape of his life before and during prison, “hopped up on / dopeboy vernacular” and the lyric voice from Frank Bidart to Kendrick Lamar, disassembling “the trap of American manhood,” pondering how his absence from an ex-lover is like the time he collided with the windshield in a car accident and nearly died, “the darkness we talk about but can’t really / grasp like fish speaking of space two layers / of clouded air & blue light.”

In this roiling, self-aware debut, the readers themselves are judge, jury, and peer: “The page, as it lives in each of our minds, is our courtroom.” What we judge is a man, his teenaged self, the carceral state, our class and educational caste system, his contrition towards his victims, and the possibility of redemption. “I want to be / A zero / No longer,” he writes. From his poetry we know this already to be true.

Chris Nealon, All About You

“I never brag in poetry,” writes Chris Nealon in his fifth book, “but what are these moments if not the ones in which I know what I’m a part of? / A ripple with a brain whose sparks are stars.” With a poetic line that tends to long, unbidden gestures (“The flung arm of a dancer”), the ripples of his mind engage with artful spontaneity on meaningful moments in his life: a father’s death, the landscapes of memory, the work of poetry, the childhood origins of a sensibility (“Launching a life of referring to singers by their first names—so gay!”) .

Self-effacingly, he claims allegiance to the Magic 8 Ball as his modus operandi: “Shake it! Shake it! / That’s your sense of form.” And yet this may be the crafted deflection of a poet in a lineage of the New York School, who knows that charm and nonchalance make a potentially daunting depiction of consciousness go down easy. “O cascade of one-line strophes,” he says. “You fall like flour through a sifter.”

A passage about attending a reading by the superb Douglas Crase richly depicts how poetry, including Nealon’s own, gains admission into our minds, “phrases building up to what at first I thought was crystal pivoting—this way, that way,” until we arrive at a glimmering neologism that suggests the mystery of artistic creation: “Alert— / The bardcode shone—” Nealon’s “bardcode” offers the star-like sparks of a poet’s mind deciphering our mysteries: “The beautiful lofty things we do that we can’t see— / Making gestures for each other out of the churn.”

Robert Pinsky, Proverbs of Limbo

If we’re lucky and enduringly brilliant and born in 1940, we may find ourselves approaching the making of poetry with what I imagine to be the enlightened qualities that generated such longevity in the first place. We may focus less on the mind-expanding provocations of Blakean “proverbs of hell” than on richly ambivalent apothegms, morally textured and attuned to the tenuous distinctions of the world, perched somewhere between “the flames of Righteousness / And the pits of Euphemism.”

We’d know that a Seinfeld reference might feel incongruous because maybe we “live more in the fifties than the nineties,” but we’d balance our summoning of the passing slurs that a person of any identity can’t forget (Henry James likening immigrant Jews to “snakes”) or of the lost friends from our youth, like the poet Henry Dumas, “shot dead by a transit cop” in 1968, with the dynamic scope that age and wisdom can afford, “the crowd of names all stranded alive, /Ashore, outwaiting my shadowy boat.”

Such scope is beautifully realized in the poem “Soul Making,” which zooms outward to the “galactic broth” that “brews the first suns” and then inward to the “microscopic animals, flexing / Bizarre mandibles, that patrol my eyelids / And guts.” Wielding a colloquial line that acts as a delicate, sonic zoom to the eloquent pentameters of poetic tradition, like those of Hardy and Donne, Pinsky arrives at an unforced and moving connection between himself and those eyelash mites: “Darkling I too perform the turns and bits / Of my assigned proportions.”

One of the achievements of Robert Pinsky’s work has always been the way in which he balances a realistic and therefore fateful sense of life with a vivacity of expression that reflects his unabashed pleasure in the vagaries of human nature, a sense of moral and aesthetic proportion that Proverbs of Limbo splendidly exemplifies.

Donald Revell, Canandaigua

To arrive at the voice that inhabits these poems is to have ranged for decades through our wasteland of literal-mindedness (“I am near death because of the death of allegory”) while adhering faithfully to poetry as “the groundless belief in fearful / Attention.” What Donald Revell attends to in his fifteenth collection, with a measured gravity that can enable more fearful symmetries, are the poetic themes that appeal to a sense of timelessness across generations, of love, mortality, the vanity of human wishes, and the sacred.

Great fires in the west remind him of God, who “Walked through the woods and the woods / Vanished behind Him. Faith / Is the archaic praise of that vanishing.” The divine truth of such an assertion is less important, for me, than its power to endow the poem with the brimming sublimity of something larger than ourselves. Elsewhere, with similar power, he writes, “Love is absolute, and justice / Shelters like an insect at its root,” and “what is human in us dreams across / Our own humanity without caution, with / Only zero and jubilation in mind.”

When he turns to the poetic trends of the moment (“Posterity is abandoned / To imaginary animals. / Race abdicates. Gender abdicates.”), the critique, lyrical and therefore unargued, ironically enmeshes his work in the same abandonment of posterity that he reviles, summoning its own provincialisms, racial, gendered, generational. What I return to in Revell’s work is an abiding eloquence that emulates the beauty and terror of life: “I think of faces, each lifted and withheld, / With history and its Homeric swineherds / Crowded against a kiss. Birds feed on faces.”

Tayi Tibble, Rangikura

If “Ranginui” is the Māori sky father and “ikura” is the term for menses, the title of Tayi Tibble’s second collection evokes both sacred tradition and a young woman’s coming of age: “learning from the red sky.” Born in 1995 in Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Tibble explores what it’s like to grow up “tacky and hungry and dazzling,” the Māori “off-cast of half-castes,” “tagged in / white man’s law /and wāhine blood.”

What dazzles about Tibble’s work is the dynamic array of Māori words and youthful slang to depict a passionate strut through life, its unapologetic vices (toking “until I was chill chill chill and basically brain dead”) and frank sexiness (hoping a man “might lick my blunt with his pūkana”).

With the aim of an artist eyeing the long haul, Rangikura turns inward as well, knowing the drawbacks of being “a passenger in a vehicle going so fast that the soul leaves the body.” The poems here suggest the arc to come, turning the familiar caprices of self and failed romance to the ancestral terrain from which the world as Tibble knows it arose: “our old magic, / our old ways, our bloodlines, / our trust in the river, / when we first hopped in that / souped-up waka / & looked up at the stars.”

Heather Treseler, Auguries & Divinations

Carefully ensconced in allusions to the greats of other eras (Shakespeare, T. S. Eliot, Catullus, Wagner, Gertrude Stein, Elizabeth Bishop), the stanzas in Heather Treseler’s first full-length collection yearn to burst out of living “in a rectangular fashion, by right / angles, in rooms assigned their functions.”

While the moral sensibility is attuned to liberation, both womanly and erotic (“I am the feral creature / who wanders the street…not a stitch under her skirt”), the artistic sensibility temperamentally gravitates to what remains decorous yet telling, as when a mother’s beauty persists even through the debilitation of an illness, purpura, that renders her skin like the “lavender / hat in Seurat’s famed painting.”

This tension between personal liberation and poetic orderliness is most gainful and affecting in the neatly rectangular tercets of “The Lucie Odes,” which elegiacally recounts an affair with an older woman, whose first husband pimped her out to obtain cash for an Alabama “fried chicken franchise” but who flees to become a laboratory technician and much more, the speaker turned into “comrade, confidant, chérie,” their love affair weaving a “tacit fabric” from the “evident brokenness” of their lives.

Treseler’s book contemplates love and womanhood, childlessness, and the transitory home that eros makes of flesh, building a rainy habitation from the rooms of her stanzas: “Back home, the smell of your skin resined / on mine, sweet and musky as geosmin, / ozone, petrichor….”