Hilary Mantel on How Writers Learn to Trust Themselves

“Just write as well as you can.”

Interviews seldom offer the chance to say anything worth hearing, no matter how well-prepared the interviewer. You are invited to rehash your material, saying it again in worse words. “What did you mean when you said….?” etc. Or “Why did you write this book?” It isn’t enough to say that you wrote it because it’s your job and you thought readers would like it.

I once heard Salman Rushdie in discussion on stage in St Louis, and he said that there’s only one question to ask an author. You point to a sentence, and say, “How did that get there?” Then a tale unfolds, the book’s hinterland. You get to see the shadows moving behind the substance.

Discussions with an audience are often more enlightening than interviews. You have witnesses, and parity, and might discover something even as you speak. In press interviews the author feels guarded and wary. And for my part, I don’t feel I am providing value. I just want to get through without being quoted out of context. When you read an interview back, you seldom recognize it as a true account of what passed. It may have been transcribed exactly, but it still misses the bit where you rolled your eyes. Unless it’s on screen, if course—but then there is usually a strict time limit, and constraint and self-consciousness.

What I’d always like to hear about, from other writers, is their beginnings—including the part of their lives before they consciously stated, “I am going to write a book.” I am especially curious about those who, like myself, come from an unliterary background—where a book was the last thing anyone expected from you.

*

Time of day: early. I have to grab a notebook and write by hand before I am properly awake. I don’t write down dreams every day—sometimes they’re too confused and elusive. But they stain my mood if I don’t work them off—it’s like an ache in the muscles that you can ease by movement. Then I wake up slowly, and don’t want to talk. The day’s writing starts to unroll in my head. It’s fragile and often a matter of rhythm rather than words. If I don’t have the time to jot something down, I will have to work myself back there later, laboriously; best to do it while it’s easy.

So my favorite day is one where I can sleep till I wake, and my humble ambition is to have as many of these as possible. It doesn’t necessarily mean a late start—if I have an idea before dawn, that’s when work starts.

I get my admin done by noon if I can, and push it out of my mind so I can do some real work. I feel shy of saying this, because to non-writers it sounds so lazy—but if, seven days a week, you can cut out two hours for yourself, when you are undistracted and on-song, you will soon have a book. Unoriginally, I call these “the golden hours.” It doesn’t much matter where I find them, as long as I do. I usually work many hours more. But sometimes I wonder why.

Your best days are sometimes those when you end up with less on the page than when you started.You must recognize, though, that once you enter this life, you are at the disposal of your book around the clock. And there are no holidays.

*

I am dubious about the existence of blocks or frustrations peculiar to writers. Sometimes people claim they are blocked when they have nothing to say, or they have, temporarily anyway, exhausted their subject; this is not pathology. Sometimes a project goes into an incubation period; as I’ve said very often, the moment you have a good idea isn’t always the moment to see it through. Writing is a long game and you have to be patient with yourself and your material. A great deal happens in the dark, as it were; work goes on half-consciously. You have to trust this process is happening.

Of course, writers find it difficult to trust themselves. It can seem such an inflated claim, that you are a writer. So you think you have to keep proving it, by persecuting paper with ink or pounding the keys, as if you need a self-justifying witness to your own strength of purpose. But there’s no point in having a healthy word-count, unless they’re the right words. Writing’s not an industrial process. You can’t measure your productivity day-to-day in any way the world recognizes. Compression is the first grace of style and takes hard labour. Your best days are sometimes those when you end up with less on the page than when you started.

Maybe plain old depression is to blame for much of what afflicts writers—the kind of depression that dogs people of all trades and none. The conditions are right. The work requires a deliberate cutting-off from other people; you have only yourself to depend on, because no one will do it for you; your income is uncertain; at the end of the process you surrender control, dependent on the judgment of strangers; you face a lot of rejection. Why wouldn’t you be depressed? The surprise is that thousands of people hurl themselves into this occupation, year after year.

*

The best advice came from my agent, when I was a year or so into my career. I was dithering about a future project, saying that there was a way to do it that would be accessible and commercial, and a way to do it that would be smart but unpopular. He said, “Just write as well as you can.”

That advice has saved me years. I never again asked the question, of myself or anyone else. It’s the only way to work—don’t write to what you perceive as a market. Don’t write out of anyone’s need except your own. Don’t try to cater to an audience you think may not be keeping up with you—find the audience who will. I have amplified the advice in my mind: just serve your subject. Each book makes different and fierce demands. Each one uses up all you can do. Later you may be able to do more.

I think writers need tolerant people around them. They’re prickly and strange and needy, yet they demand to be left alone.Something else that helped me was not a piece of advice so much as an observation. At the beginning of my career, if I wrote a column, review or any short piece of journalism, I would perfect it as best I could, but I couldn’t bear to read it once it was in print; my eyes would slide over it as if it were a corpse. An early patron of mine was Auberon Waugh, a writer and journalists of vast experience. One day he asked me, “Can you bear to read your stuff again? I can’t read mine.” He looked sick at the very thought.

I felt immense relief. I’d thought I was a solitary coward, but I saw I wasn’t alone, and time wouldn’t mend my condition. It’s hard to accept, but part of growing up in the craft is to know that not everything you write matters. I soon forgot most of what I delivered, and a good thing too. As long as it’s clear, accurate, entertains momentarily and is not libelous, you’ve achieved your aim and can stop worrying.

This is not true of long-form prose or any form of fiction. You ought to live at peace with your backlist.

*

Early drafts, bits and pieces: I ask my husband, who used to be a science editor, to read maybe fifty pages of a novel at a time, to see if I’ve got any basic grip on sense. I don’t expect a literary opinion from him. Really, I want him to reassure me. He does this very well. If he thought something wasn’t clear, I’d be slightly offended—but then I would take notice.

I think writers need tolerant people around them. They’re prickly and strange and needy, yet they demand to be left alone. First readers need to be aware of what they’re being asked; it’s mostly for moral support, but any evidence of close reading and real appreciation is welcome to the wretch who feels she’s walking in the dark—it’s as if someone has switched on a light and said, “This way.”

For different books I’ve had different readers. Friendships move on and some people link naturally to certain projects. The early reader has to act as a witness to novel’s formation, because there are times when it feels it might slip away and resolve back into its elements. For The Mirror & the Light, my first reader was the actor Ben Miles, who played Thomas Cromwell, my main character, on stage. And the same email attachment would go to his brother George, a photographer, who sees more than I do and I suspect writes better too. I felt that once they had read it, in however temporary a form, it wouldn’t entirely melt from the page.

__________________________________

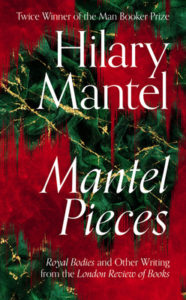

Mantel Pieces by Hilary Mantel is now available via HarperCollins.