Hiding In Plain Sight: Patrick Gale on the Life and Work of Poet Charles Causley

“Only then did I reread the poems, to see how they might be transformed by the things I had learned.”

I have no idea if Charles Causley’s poetry is known to American readers but I suspect it isn’t, or only to scholars and other poets; to become internationally celebrated for poetry requires the kind of ambition he signally lacked. He was without question one of the most important British poets of the last century—utterly original, his working-class voice untainted by university and the dead weight of literary tradition it passes on, and abidingly popular without being populist.

A poet’s poet, his furious polemic about child neglect, Timothy Winters, remains among the most memorized of the poems the British learn at school; on a recent book tour I found I needed only recite the first two lines to any UK audience for a merry hubbub to break out as people joined forces to recite the rest back at me.

Eden Rock, his masterpiece evoking both grief for dead parents and intimations of mortality, rubs shoulders with Auden’s Funeral Blues, Tennyson’s Crossing the Bar and Clare Harner’s Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep, in the forefront of those poems unthinkingly chosen as funeral readings or emailed to bereaved friends.

Causley’s reputation is in trouble, though, not through one of those posthumous scandals where a much loved writer is exposed as vile to women or collecting schoolgirl porn or whatever, but because of the efficiency with which he constructed an irreproachable public persona. Of our great poets, he less sexy even than Larkin. There are no drugs, no benders, no vendettas, no suicidal lovers, no lovers, indeed.

The facts of his remarkably unadventurous life are swiftly summarized: born in Launceston, a small town on the Cornish border, in 1917 to a Cornish mother and Devonian father who had met as servants, taken out of school at fifteen because his widowed mother needed him to work, a sailor in the Second World War, then a schoolmaster in the tiny junior school he had attended himself. He lived with his mother until she was carried off by old age and only then became a full time poet, befriended and championed by the likes of Hughes and Heaney, beloved by the BBC (you can hear several of their recordings of his lilting, mischievous accents if you Google him) yet remaining obstinately in his sleepy Cornish backwater until his death.

Two volumes of his work remain in print—the collected poems for grown-ups and the no less enchanting collected poems for children (test-driven on the adoring pupils he taught at the little National School). To this day if you encourage Launceston locals to talk about him, it’s significant that they tend not to call him Charles, with the ready intimacy of those of us who love his poems, but Mr. Causley, retaining the respect he fostered as a schoolmaster.

“Leading Seaman Walker” (of Charles’ doomed ship), painted by Eric Henri Kennington. Copyright © Imperial War Museum, London.

“Leading Seaman Walker” (of Charles’ doomed ship), painted by Eric Henri Kennington. Copyright © Imperial War Museum, London.

I was prompted to write a novel about him by the startling news that his work—beloved of teachers for its combination of inventiveness and accessibility—was being taken off the National Curriculum, no doubt in favor of an author perceived to be less stale, male and pale. When I first moved to Cornwall as a young novelist I lived just down the road from him and I heard rumors enough to make me suspect there was more to his life than the official version. Stumbling across his long out-of-print collection of short stories—Hands to Dance and Skylark—which are shot through not merely with naval saltiness but unmistakable shafts of camp seemed to confirm this.

As with my novel A Place Called Winter, in which I solved the mystery of a rich great-grandfather’s having abandoned his wife and child by suggesting he was caught out in a secret gay scandal that obliged him to start a new life as a homesteader in the Canadian prairies, I pledged to honor any fact I discovered, however inconvenient. I researched in as much mind-numbing detail as if I was producing a biography. I spoke to every surviving adult who had known him in youth and to married women who had clearly been rather in love with him as an adult.

I spent time living in Cyprus Well, the last house he shared with his mother as well as in Gibraltar, Malta, Liverpool and Skegness, the places he had worked in during the war. I toured a battleship with a naval historian, wrecked my eyesight deciphering his tiny secret diaries, read every surviving letter that had survived his filing system (a compost heap of paper in his leaky garden shed), pored over coding manuals and machinery and listened to many hours of oral history compiled by the Imperial War Museum. And only then did I reread the poems, to see how they might be transformed by the things I had learned.

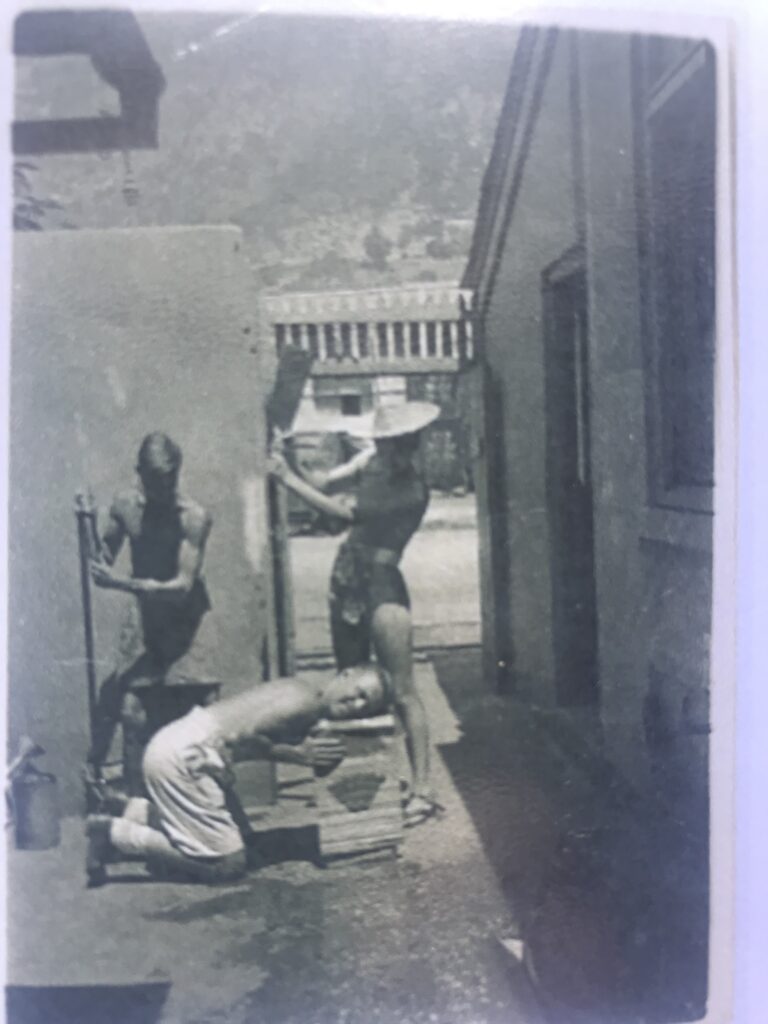

Charles and amateur dramatic friends in Gibraltar. All photographs courtesy of the Charles Causley Trust (www. https://causleytrust.org).

Charles and amateur dramatic friends in Gibraltar. All photographs courtesy of the Charles Causley Trust (www. https://causleytrust.org).

All my novels are powered by questions which can often ultimately only be answered by using fiction to join the tantalizing dots. In this case there were two. Why did a working class boy who, despite an education cut brutally short, was having considerable success as a playwright before the war, return from it a poet? And why, having spent the 1930s despising Launceston’s conservatism and narrow outlook and impatient with his mother’s piety and suffocating love, did he then elect to return there and share a house with her until her death?

Charles was scarred for life by survivor’s guilt.

The answers to these questions are interdependent. Reading the diaries over Charles‘ shoulder, as it were, I kept catching glimpses of a young man censorious as the sexually repressed tend to be, impatient with the gushings and enthusiasms of his much more out there friend Ginger, briefly revealing himself when the two of them find themselves surrounded on the grass of Plymouth Hoe by a horde of sunbathing sailors (“Oh! How I wished I could draw!” he writes, giving two rare examples of a Causley exclamation mark.)

And then his captain takes pity on the chronically seasick young sailor and transfers him to a land posting in Gibraltar where the sun comes out emotionally as well as physically. The writing changes, relaxes, as Charles gets to camp around in amateur dramatics and meets louche characters closer to Isherwood’s Berlin than his Cornish roots.

But then the diaries stop abruptly—evidently stifled by both a personal and official need for secrecy—and I was obliged to piece together the rest from letters and postcards. I was just beginning to wonder whether I was projecting too much of myself and my own provincial gay story onto Charles when I came across a terse missive from a naval officer which was, quite simply, a Dear John letter.

The officer thanks Charles for getting in touch and appreciates all the fun they had together in the signals training station HMS Cabala, near Liverpool, then startlingly asks that Charles write nothing further he wouldn’t mind the officer’s wife reading because he’s now a respectable married man and putting all that sort of thing behind him. I read the letter repeatedly, and asked a heterosexual colleague to read it as well in case I was interpreting it wishfully, and then everything fell into place.

Charles and friends larking about outside the Gibraltar signals mess. All photographs courtesy of the Charles Causley Trust.

Charles and friends larking about outside the Gibraltar signals mess. All photographs courtesy of the Charles Causley Trust.

For Charles was scarred for life by survivor’s guilt. His ship, the HMS Eclipse, was sunk in the Mediterranean with all hands lost and the only survivors were a man put ashore with appendicitis and Charles, who had been found another land posting so that he could sit the exam to progress to petty officer status. The shattering news of the loss would have reached him during his involvement with the officer at HMS Cabala and it was there that he wrote one of the first of his sequence of extraordinarily tender war poems.

Rattler Morgan is just two stanzas long and shows the influence of Ariel’s song from The Tempest, which Charles (and I imagine the officer) had recently seen together in Liverpool Playhouse. Set far from the noisy horrors of sea battle, it simply pictures a drowned sailor at mildly eroticized peace on the ocean floor, “fumbled by ancient tides”, his hair adorned with starfish.

In later life Charles often repeated that the Navy was his Eton and Harrow, his Oxford and his Cambridge in that it taught him so much about men and life and completed the education his mother’s need for him to earn a wage had cut short. And there’s no question that for him, as for so many working class men ripped away from quiet country backgrounds by enlistment, war showed him the world (in his case Sierra Leone, Australia and the South Pacific as well as the countries of the Mediterranean) and threw him into company he would never have found back home.

But I believe its most invaluable gift to him was coding. He was recruited as one of the first generation of on-board naval coders, who task was swiftly to decode signals received in Morse and to encode any outgoing signals. The work was pressurized, conducted in an airless, overheated little office, and made no easier by the combination of Charles’ constant seasickness and terror of violent death, yet he discovered he had a gift for it.

War was no place to write the sort of brittle social comedies he had been writing, seeing published and even broadcast in the 1930s, but he found it was perfect for poetry as he could carry a stanza or two in his head and, astonishingly, revisit and polish them with one part of his brain while he was coding with another. He wrote the one collection of naval short stories and abandoned a Gibraltar-set novel that might have stood alongside Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy and I believe this retreat from fiction into poetry parallels the need to stop confiding in diaries and was born of a need for discretion and secrecy.

Charles as a little boy with Laura not long after his father’s death from TB. All photographs courtesy of the Charles Causley Trust (www. https://causleytrust.org).

Charles as a little boy with Laura not long after his father’s death from TB. All photographs courtesy of the Charles Causley Trust (www. https://causleytrust.org).

Terms like gay are inaccurate and inappropriate when applied retrospectively to men who were never comfortable with, or open about, their sexualities. But what we would term gayness was dangerous in his era, punishable by court martial and official disgrace in the Navy and by imprisonment at home. I believe Charles was driven home after the war partly by survivor’s guilt—by the knowledge that he was one of very few of his generation in Launceston to return from the sea alive—but also by the need to dress himself in the ultimate respectable persona which didn’t require an honorable man to tell any lies: the cheerful country schoolmaster who was good to his mother.

Having stayed in their tiny house (sleeping in Laura’s bedroom as I didn’t dare sleep in Charles’s), I had a powerful sense of their domestic dynamic in which any woman who set her cap at Charles, or any man for that matter, could only get to him through Laura, whose formidable presence guarded his study at the rear from her armchair in the front room. It explains in part why her eventual death brought on a crisis of grief that was a kind of nervous breakdown, for it left him unshielded from a gossiping world.

As I say, I returned to the familiar poems with keener eyes after spending months among Charles’ private papers. I had always planned to let him have the final word and found that one poem in particular now jumped off the page at me and demanded I structure my final chapter to suggest an explanation for it before ending the novel by quoting it in full.

Angel Hill is, superficially, a typical Causley poem in that it takes the form of a singsong ballad and tells a story. It shows the poet unexpectedly visited at home by former shipmate, a sailor who reminds him insistently of the promises they made one another at sea, promises of fidelity to the point of love. “I bound your wounds and you bound mine,” the sailor says. And in the refrain, repeated after every verse, the poet denies him, like Peter denying Christ. Before my research I had always read the poem as a ghost story—the sailor’s threatening last line is, “I’ll send and I’ll fetch you one fine day”—but now, given that Angel Hill is the name of the precipitous back lane where Charles and Laura’s last house, Cyprus Well stands, I realized the poem is a confession hiding in plain sight.

__________________________________

Mother’s Boy by Patrick Gale is available from Tinder Press, an imprint of the Headline Publishing Group, a division of Hachette Book Group UK.

Patrick Gale

Patrick Gale was born on the Isle of Wight. He spent his infancy at Wandsworth Prison, which his father governed, then grew up in Winchester before going to Oxford University. He now lives on a farm near Land’s End. One of this country’s best-loved novelists, his most recent works are A Perfectly Good Man, the Richard and Judy bestseller Notes From An Exhibition, the Costa-shortlisted A Place Called Winter and Take Nothing With You. His original BBC television drama, Man In An Orange Shirt, was shown to great acclaim in 2017 as part of the BBC’s Queer Britannia series, leading viewers around the world to discover his novels.