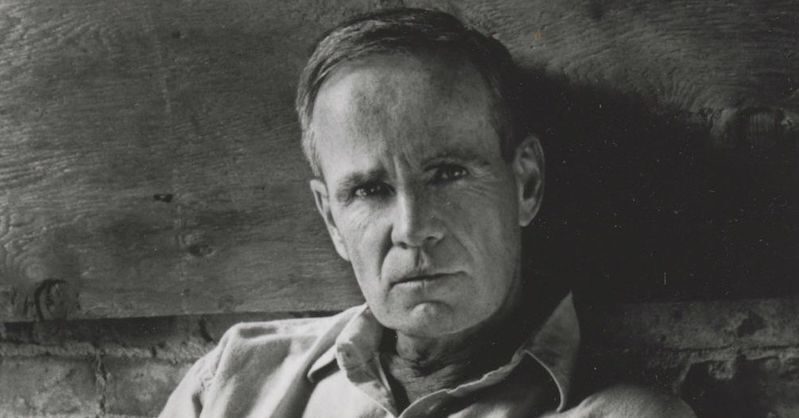

Hero of a Cult of One: On Loving Cormac McCarthy’s Early Work

Jason K. Friedman Considers the Enduring Creative Influence of a Now-Beloved American Writer

In my freshman year at Yale, an English teacher gave me a bootleg copy of Cormac McCarthy’s 1973 novel, Child of God. The pages had been xeroxed and spiral bound, with a blank page of green construction paper serving as a front cover and the New Yorker’s review of the book, entitled “The Stranger,” as a preface.

Child of God wasn’t on the syllabus of English 129a; those books I had to get for myself. Most of the classics of Western Civ that we studied back then sit untouched today in my living-room bookcases, whereas Child of God, that hand-made version, lives on a shelf by my desk, along with a few other books I keep close, officially for reference but truly for inspiration.

When Professor D gave me this book, eight years after its publication, Child of God was out of print, along with McCarthy’s two earlier novels, The Orchard Keeper and Outer Dark, though they would all be reissued over the next few years in a series called Neglected Books of the Twentieth Century. Such was the fate of fiction written in a prose both austere and lavish, marked by Biblical cadences and modernist affectations and full of antique Anglo-Saxon words, and granting the reader none of the traditional concessions that make novels seem real and characters relatable—not a word of interiority, for example—and none of the plot devices, like love stories and weddings, that have made the English novel such a gossipy pleasure. Then there’s the subject matter, like brother-sister incest and filicide: Outer Dark. And necrophilia: Child of God.

I was aspiring to a romantic ideal that no one more than he represented.Surely there were ways for devotés of obscure books to find one another in the days before the Internet, but I didn’t know or care to know them. Occasionally I turned a friend on to him, but otherwise my relationship with Cormac McCarthy was exclusive. As far as I was concerned, he was the hero of a cult of one.

After graduation, I moved to New York and got a job at the Strand, which billed itself as the world’s largest bookstore. It was a wonderland of books, and the basement, where I worked in the mail-order department, was its hell. Humansize fans stirred the hot air and sent dust mice scuttling across the floor. The subway roared unseen around us.

What meager wages I made I mostly returned to the shop, in exchange for books at a steep discount. Friday afternoons I waited to check out in a long line of employees, all with comically tall stacks of books, as if they were being sold by the foot.

My job was data entry. I input addresses from mail-order requests, letters from all over the world. One day on my pile there appeared one, short and typewritten, from Cormac McCarthy.

I can’t recall what he was ordering, maybe because I was so startled by the address, in El Paso. How did a Texan write these Deep South books? He must have moved—according to that New Yorker review of Child of God, he lived in the “high country of Tennessee”—but if so, what would this mean for his work? What was he moving on to?

I input the address into the newfangled computer system and, when my boss had gone to retrieve his lunch, into my own address book.

The El Paso thing struck a chord because I myself was a displaced Southerner, a Savannahian now living in a tenement apartment in Alphabet City, where my bedroom was so tiny that my single bed served as a chair for a desk—nothing but these two pieces of furniture would fit. I was writing a novel about an undead trucker who travels the highway taking revenge for his accidental death. The book, while bad, had a dry humor and gothic atmosphere imitative of my hero.

But in that downtown hole I was worshiping him more than his books. After the Strand I worked as an editorial assistant at a Manhattan publishing house, a place Cormac McCarthy, at least my version of him, would never have been caught dead in. But the poverty wages I was still earning, my humble domicile, my devotion to my art—I was aspiring to a romantic ideal that no one more than he represented.

I could live this life, I was living it. New York was my El Paso.

But that Texas town turned out to be something for Cormac McCarthy other than a place of exile. El Paso, and the West in general, gave us Blood Meridian, published just before I started working at the Strand, when I was still catching up with my hero’s books. The novel is a gory anti-Western about a nameless “kid” who takes up with a borderlands gang that slaughters Native Americans, for the bounty on their scalps, and anyone else who gets in their way. It’s a merciless book, hard to read for the violence and the vocabulary, but philosophically rewarding in its depiction of a world so full of evil as to trouble the possibility of goodness itself. It’s McCarthy’s greatest work, his genius feeding on the mythos of his new home as it had in his birthplace.

Blood Meridian and Suttree, which I discovered as a Vintage Contemporaries paperback that came out in 1986, a year after I’d graduated, shone a light on my self-delusion, but it was only with 1992’s All the Pretty Horses, the first volume of the Border Trilogy, that things really changed. No amount of denial could convince me that Cormac McCarthy was mine alone, not anymore. I summoned a spirit of generosity and tried to feel glad that the greater reading public had discovered him, I did!

In All the Pretty Horses, set in Mexico and the West, concessions to the reader were still few—much of the dialogue is in Spanish, for example, though through the author’s skill you understand it even if you don’t speak the language. But for the first time now there’s a love story, with both partners unrelated and alive. Now instead of backwoods perverts, cowboys! Publishers Weekly alluded respectfully to the earlier novels but announced All the Pretty Horses as a “singular achievement,” a departure—and they meant this in a good way. Now Cormac McCarthy had a bestseller—and a movie deal.

Betrayal brings disenchanted lovers together. Suddenly people around me were coming out as Cormac McCarthy aficionados—but of his early work, we were all quick to specify. Before he became a Beloved American Writer. It’s an old story, familiar to fans in all genres, but this was my story and I felt it as a loss.

Over the years I’ve wondered why Professor D gave me that copy of Child of God. She was teaching a section of a huge survey course, she couldn’t have had much control over the syllabus of tried-and-true classics; maybe the gift was her way of turning me on to something mind-blowing and, at least at the time, noncanonical, something I would otherwise never have read at a tradition-bound school like Yale. On the other hand, Child of God isn’t so out of place, thematically, on a list that starts with the Iliad and the Oresteia (murder, fate), moves on to Oedipus the King (incest, also murder and fate) and The Book of Job (merciless God), and ends with The Cherry Orchard, which like Child of God begins with auctioning the family land.

We didn’t talk much about the book, my teacher and I, though once during her office hours I reported that I’d read it, and that it seemed to me something exciting and new in literature. I didn’t know I would begin writing fiction myself, soon after, but I remember this gift as somehow connected to my writing, and not just because Child of God was the book that finally moved me to emulation. It was also because of what happened later between Professor D and me.

No amount of denial could convince me that Cormac McCarthy was mine alone.By the time, in my junior year, that I took another class with her, I was no longer that Southern kid straight off the train who’d stepped gloveless, hatless, scarfless, even sockless into his first New England fall. I’d published short stories in the college literary journals and won awards; I was a writer now and that was who I was. The surgical yet bloodless explications de texte I’d learned to do in high school had served me well in introductory classes like the first one I took with Professor D. But I was enrolled now in a high-powered class on literary theory, which was where the action was at Yale back then. It was hard and all I really wanted to do anymore was write stories.

So I missed the boat, wrote so-so papers and absented myself frequently from my first theory course at Yale, and one taught by a woman who had been a mentor since my first days there. Like a chickenshit lover I didn’t even tell her; I simply dropped the class.

Later, we ran into each other on a sidewalk by the library. She was coming from it, I was heading that way, trudging through a wind blowing dead leaves around my feet. I was dressed warmly. I knew now how to get by. But there was no way to avoid her. She seemed in a rush, she always did—my professor was a serious, intense woman, she had papers to grade, books to read and write.

And students to school. She didn’t even stop as she passed, though she half-met my eyes and spoke: “It could really have helped your fiction writing if you’d worked harder.”

And then she was gone, forever.

Maybe it was this jolt of truth that made me feel that when she handed me that copy of Child of God, two years earlier, she was acknowledging me as a writer, before I even considered myself one. To this day, whenever I pick up that spiral-bound pile of raggedy photocopied pages, a tremor of shame passes through me. I’d failed my mentor, and myself, no denying it, and while I’d never get the chance to live up to her expectations again, I would have the chance to live up to my own, or not, every day of my life.

I still have Cormac McCarthy’s address. Once, on a cross-country Trailways trip, I’d planned to visit him. I would profess my admiration, relate the story of how my teacher turned me on to him, maybe apologize for the copyright infringement. Luckily I wised up and stayed on the bus. It’s too late to ambush him now but maybe it always was. I must have suspected, even as a young man, that the last place you’d ever meet your hero is at their front door.

__________________________________

Liberty Street: A Savannah Family, Its Golden Boy, and the Civil War by Jason K. Friedman is available from University of South Carolina Press.