We know life is finite.Why should we believe death lasts forever?

*

The shadow of a bird moved across the hill; he could not see the bird.

*

Certain thoughts comforted him:

Desire permeates everything; nothing human can be cleansed of it.

We can only think about the unknown in terms of the known.

The speed of light cannot reference time. The past exists as a present moment.

Perhaps the most important things we know cannot be proven.

he did not believe that the mystery at the heart of things was amorphous or vague or a discrepancy, but a place in us for something absolutely precise. he did not believe in filling that space with religion or science, but in leaving it intact; like silence, or speechlessness, or duration.

Perhaps death was Lagrangian, perhaps it could be defined by the principle of stationary action.

Asymptotic.

Mist smouldered like cremation fires in the rain.

*

It was possible that the blast had taken his hearing. There were no trees to identify the wind, no wind, he thought, at all. Was it raining? John could see the air glistening, but he couldn’t feel it on his face.

*

The mist erased all it touched.

*

Through the curtain of his breath he saw a flash, a shout of light.

*

It was very cold.

Somewhere out there were his precious boots, his feet. He should get up and look for them.

When had he eaten last?

He was not hungry.

*

Memory seeping.

*

The snow fell, night and day, into the night again. silent streets; impossible to drive. They decided they would walk to each other across the city and meet in the middle.

The sky, even at ten o’clock at night, was porcelain, a pale solid from which the snow detached and fell.The cold was cleansing, a benediction.They would each leave at the same time and keep to their route, they would keep walking until they found each other.

*

In the distance, in the heavy snowfall, John saw fragments of her – elliptic, stroboscopic – Helena’s dark hat, her gloves. it was hard yet to tell how far away she was. he shook the snow from his hat so she might see him too.yes, she lifted her arms above her head to wave. only her hat and gloves and the powdery yellow blur of the street lamps were visible against the whiteness of sky and earth. he could barely feel his feet or his fingers, but the rest of him was warm, almost hot, from walking. he pulsed with the sight of her, the vestige of her. she was everything that mattered to him. he felt inviolable trust. They were close now but could not make their way any faster. somewhere between the library and the bank, they gripped each other as if they were the only two humans left in the world.

*

Her small ways known only to him. That Helena matched her socks to her scarf even when no one could see them in her boots. That she kept beside the bed, superstitiously unfinished, the novel she had been reading in the park the day they understood they would always be together. The paper-thin leather gloves she found in the pocket of the men’s tweed coat she bought from the jumble sale. her mother’s ring that she wore only when she wore a certain blouse. That she left her handbag at home and slipped a five-shilling note in her book when she went to the park to read. The boiled sweets tin she kept her foreign change in.

*

Helena carried the handbag he had bought for her on the hill road, soft brown leather, with a clasp in the shape of a flower. she wore the silk scarf she had found in the market, made hers now by her scent, autumn colours with a dark green border, and her tweed coat with velvet under the collar. how many times had he felt that velvet when he held open her coat for her. A finite number. Every pleasure in a day or a life, numbered. But pleasure was also countless, beyond itself – because it remained, even only in memory; and in your body, even when forgotten. Even the stain of pleasure and its taunting: loss. The finite as unmanageable as the infinite.

*

They walked to his flat and left their wet clothes at the door. no need to turn on the lights. The blinds were up, the room snow-lit. White dusk, impossible light. John was always surprised, he never stopped being astonished, at how little there was of her, she was tiny it seemed to him, and so gentle and fierce he couldn’t breathe. he had bought the scented powder she liked and he filled the tub. he added too much and the foam spilled over the steaming edge.‘A snowbank,’ she said.

*

The young soldier was lying only a few metres away. how long had the boy been staring? John wanted to call out to him, make a joke of it, but couldn’t find his voice.

*

Pinned to the ground, no weight upon him. Who would believe light could fell a man.

*John’s child-hand in his mother’s hand. The paper bag of chestnuts from the vendor with the brazier in front of the shops, too hot to hold without mittens. leaning against his mother’s heavy wool coat. her smooth handbag against his cheek. Peeling the brown paper skins of the chestnuts to the steaming meat. The tram squealing on the track. The edge of his mother’s apron escaping from the edge of her coat, the apron she forgot to take off, the apron she always wore. Trams, queues, the smells of fish and petrol. her softness against his hard childhood. her scent before he succumbed to sleep, the burnished warmth of her necklace as she leaned over to him. The lamp left on.

*

The inn had been built beside the rail tracks, next to the rural station, in a river valley. long ago, the inn and the valley had been a tourist destination, promoted by the train company for its view of the mountains, the wildflower meadows, the aromatic pines and betony. The rail tracks were shadowed by the slow river, like a mother struggling to keep up with her child, silver lines running the length of the vale.

Helena had been heading for the larger town beyond, but had fallen asleep. she could not stop herself from drifting off, succumbing as if drugged by the motion of the train. And when the train stopped at the last station before the town, she had, half asleep, misunderstood the conductor booming out the next stop and had grabbed her satchel and disembarked a station too early.

Beyond the dim lamp by the exit, it was dark – profound country darkness. she felt foolish and slightly afraid; the deserted platform, the locked waiting room. she was about to sit on the single cold bench and wait for daylight, when she heard laughter in the distance. later, she would tell him she heard singing, though John remembered no music at all. she stood at the exit, not wanting to leave the pitiful protection of that single dusty bulb in the station. But, leaning into the darkness, she saw, some distance away, the inviting pool of light of the inn.

Later, she would imbue the short walk in the darkness towards that corona of light – the endless fields of invisible grasses rustling in the dark – with the qualities of a dream; the inevitability of it, the foreknowledge.

Looking into the front window, helena saw a room enclosed in a time of its own. An inn of legend, of folklore – warmth and woodsmoke. Faded upholstered armchairs, scarred wooden tables and benches, stone floors, massive fireplace, with a store of logs to last the coldest winter, stacked from floor to ceiling, the self-perpetuating supply of a fairy tale, each log, she imagined, magically replacing itself over the centuries. John watched as she sat down nearby. it was, to him, an encounter of sudden intimacy in this public place; the angle of her head, her posture, her hands. he watched as a man – soused and staggering, every careful step an acknowledgement of the spinning earth and its axial tilt – fell into the vacant chair opposite her, giving helena a slow, marinated gaze until his head fell, heavy as a curling stone, and slid across the table. John and another onlooker jumped up to help at the same time and, between them, dragged the man to the back of the pub to sleep it off.When John returned, he found his own table taken by a couple who did not look up, already lost to the room around them.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Helena said, quickly gathering her coat and satchel, ‘please, take this table.’

He insisted she stay. With a great effort past shyness, she asked if he would care to sit with her. later she would tell him of the feeling that passed through her, inexplicable, momentary, not even a thought: that if he sat down she would be sharing a table with him for the rest of her life.

*

In the little window in the hallway, from the heat of the bath, they could see the snow falling.

*

The black lines of the trees reminded him of a winter field he’d once seen from the window of a train. And the black sea of evening, and the deep black bonnet and apron of his grandmother climbing up from the harbour, knitting all the while, leading their ancient donkey burdened with heavy baskets of crab. All the women in the village wore their tippie and carried their knitting easy to hand, under their arm or in their apron pocket, sleeves and sweater-fronts, filigree work, growing steadily over the course of the day. Each village with its own stitch; you could name a sailor’s home port by the pattern of his gansey, which contained a further signature – a deliberate error by which each knitter could identify her work. Was an error deliberately made still an error? Coastal knitters cast their stitches like a protective spell to keep their men safe and warm and dry, the oil in the wool repelling the rain and sea spray, armour passed down, father to son. They knitted shorter sleeves that did not need to be pushed out of the way of work. Dense worsted, faded by the salt wind. The ridge and furrow stitch, like the fields in march when they put in the potatoes. The moss stitch, the rope stitch, the honeycomb, the triple sea wave, the anchor; the hailstone stitch, the lightning, diamonds, ladders, chains, cables, squares, fishnets, arrows, flags, rigging. The noordwijk bramble stitch. The black and white socks of Terschelling (two white threads, a single black). The goedereede zigzag. The tree of life.The eye of god over the wearer’s heart. if a sailor lost his life at sea, before his body was committed to the deep, his gansey was removed and returned to his widow. if a fisherman washed ashore, he was carried home to his village, the stitch of his sweater as good as a map. And once restored to home port, his widow could claim his beloved body by a distinctive talisman – the deliberate error in a sleeve, a waistband, a cuff, a shoulder, the broken pattern as definitive as a signature on a document. The error was a message sent into darkness, the stitch of calamity and terror, a signal to the future, from wife to widow. The prayer that, wherever found, a man might be returned to his family and laid to rest. That the dead would not lie alone. The error of love that proved its perfection.

__________________________________

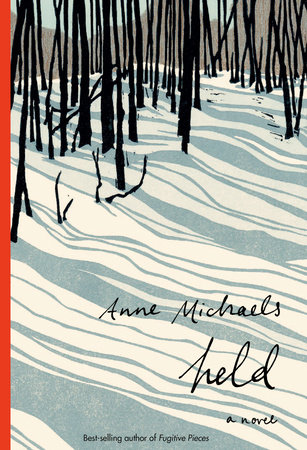

From Held by Anne Michaels. Used with permission of the publisher, Knopf. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Michaels.