Lee was in the Hall Three booth trying to decide whether this Suicide album belonged in the “Electronic Pioneers (~60s/early 70s)” section next to Silver Apples or before Television in the “First Wave Punk— NYC” section—the album came out in ’77 but the band played its first shows as early as ’71, nearly a half decade removed from punk’s watershed year—when the countergirl Ellie emerged Spicoli-style from the restroom in a cloud of pot smoke. She slowed as she passed, staring at him with dilated pupils, her brow a question mark punctuating the do I know you? expression on her face.

But no, she didn’t know him, not as anything but one of the new dealers. He had a familiar look, that was all—not a famous or handsome or notable one—just familiar. He seemed to fit in anywhere, even when he tried not to. Unfamiliar hands constantly grasped his shoulder. Wives marveled that he looked just like their husbands. At airports, strangers trusted him to watch their bags while they used the bathroom. He was distinct enough to attract attention, but somehow also bland enough to be as quickly forgotten, like a character actor cast in different roles in separate episodes of Law & Order.

Anyway, the girl was just stoned. Not as if she’d know him from his photo on the inner sleeve of the debut (and only) album by his punk band Tears in the Birthday Cake, which went out of print and into remainder bins almost immediately upon its limited 1987 release. And she was far too young to recognize him from his brief and embarrassing stint in the Sodashoppe Teens, a long-forgotten group of Bay City Rollers wannabes thrown together by producer Don “Lollipop” Llewellyn in the mid-70s, just a bunch of dumb kids who’d responded to an ad in the back of an issue of Teen World and didn’t look at the contract too closely, whose single “Handclaps in My Heart” scraped the bottom of the Top 100 in a handful of regional markets for a week or two. The band broke up after Llewellyn was arrested on child pornography charges, something related to a casting call for Sodashoppe Teenyboppers that the record company never authorized and the band knew nothing about. Today, they were trivia, only known—if at all—as an inauspicious early vehicle for then-17-year-old bass player Mickey “Street” Gordy, the Teens’ sole African American member, whom Robert Christgau once called “the Zelig of the American Avant-Garde,” now known for a diverse and critically adored post-Sodashoppe oeuvre that held a towering influence on the post-punk, no wave, indie rock, anti-folk, and nu-funk movements. Meanwhile, no one remembered or cared about Lee’s punk era, more than a decade spent in a series of bands that imploded after a handful of shows. Maybe everything would have been different if he’d moved to New York instead of Boston, but he’d wanted to keep his distance from Mickey, who Lee did not think had ever actually known his name.

So no, Lee wanted to say now that Ellie had drifted into his booth and began to finger listlessly through the crate labeled “Resort Lounge & Calypso.” You don’t know me, nothing to see here. Just a burned- out, bankrupt scenester, pushing 60 (Jesus!), who last night lay in his childhood bedroom pretending to sleep while his boyfriend jerked off to a Shaun Cassidy spread in an old issue of Tiger Beat.

Now here came Seymour out of the women’s restroom in his own weed haze. “That rich Kansas farmland grows it strong, I guess,” he said, offering Ellie a conspiratorial wink.

“I thought you were headed home,” Lee said, annoyed that he didn’t sound annoyed. There was still so much unpacking to do, and Seymour had always hated pot. He’d been weird since they’d moved—maybe since well before then, but it was especially noticeable lately.

“I’m in no state to drive. Ha, is that a pun? Is it ironic?”

“It’s bullshit is what it is,” Lee said under his breath. Now he’d have to go get the stuff from the garage himself—he needed it out yesterday, it was psychically oppressing him, all this junk left over from their shop— and risk being late for their first Dealer Association meeting.

Seymour turned to Ellie, who was staring at a Martin Denny album like it held the secrets of the universe. “Don’t tell me you’d buy that just for the cover art.”

“I own a record player,” she said defensively.

“Oh god, I hope not some 80-dollar Crosley from Urban Outfitters. Shit, I don’t think Wichita even has an Urban Outfitters. Anyway, Arthur Lyman’s better.”

“You buy things for the cover art all the time.” Lee was picking a fight, he couldn’t help it. “You’ll choose a breakfast cereal because the box color matches the kitchen.”

“Quisp is really hard to find.” Seymour eyed the Suicide record in Lee’s hand. “File it with the early electronic.”

Lee could think of nothing else to say, so he flipped past Silver Apples in the “Electronic Pioneers” crate and came upon the Sodashoppe Teens album, with its tawdry cover image of four clean-cut youths lying belly-down-feet-up on a purple heart-shaped shag rug and sipping milkshakes through curlicue plastic straws.

“Now, that is one I would buy just for the cover. Tambourine player’s a real hunk.” It was a prank Seymour had been playing for decades, hiding copies in Lee’s personal stacks to interfere with his anally hyper-meticulous organization system. Artist and genre dividers were fine for those with small collections, but Lee would never be able to find anything without dividers dedicated to era and movement and sub-movement, e.g., “Xian Acid Folk 1966–69,” “Private Press Folk Weirdos,” and “Surf Rock Instro (Cosmic).” That was just common sense. (“You might as well front-load with ELP and Steely Dan,” Seymour had said when they started to set up in Hall Three. “No one in Wichita could possibly have taste.”)

“Ha ha,” Lee said humorlessly. He replaced the Teens LP with Suicide and then tossed it into the dollar bin on the floor where it belonged.

“There is a Moog on one of those tracks.”

Seymour didn’t get the appeal of a private joke, of private anything. They’d just started doing business at the Heart of America. Lee would prefer to go at least a few weeks before word about his ignoble bubblegum pop past got out. “I think your parents were looking for you, Ellie.”

She ignored him. So did Seymour. “Hey, Ellie. Top five desert island LPs.”

“Ugh. That’s a lame guys’ game.” Ellie was still immersed in their booth’s exotica department, gazing at cover after cover like they were Magic Eye posters.

“Okay, I’ll go first.” Seymour licked his lips. “This isn’t in order.” He took a deep breath. “Pre-ranking, here are the five. Pet Sounds, obviously. You gotta have Pet Sounds. Golden Hits of the Shangri-Las. Which one goes higher? Well, it’s an issue of content versus form. We’ll get to that later. Next up—in no particular order—Mondo Deco by the Quick. Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers. And finally, well, we can’t forget Lou: 1969 Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed.”

Lee had so many records that he could listen to ten a day and die without having heard them all.“That’s six, actually,” Lee said. “The 1969 Live with Lou Reed is a double LP.”

“All right, White Light/White Heat, if you’re going to be pedantic.”

“You don’t even have that on vinyl,” Lee said.

“Sure we do.”

“I do. I’ve owned that East Coast pressing since before I knew you.”

“Pardon me for assuming we shared a love and a life. I’m only with you for your record collection, you know.”

It was almost the truth, and in that moment they both knew it. Seymour changed the subject—or rather, changed interlocutors. “So, Ellie. Top five?”

“I don’t wanna,” she said. “It’s his turn.”

“Fine. Lee? Top five?”

“It’s a lame guys’ game,” Lee said.

“So you’re a lame guy.”

Again, it was almost the truth. “I know you too well to be impressed, but you’ve got a prime opportunity to blow a young and impressionable mind here. Compared to you, my tastes are tragically conventional.”

Taste: Nothing mattered more to Seymour. Personality was a superfluous concept. Why get to know someone through conversation or confession or sex when you could just as easily scrutinize the spines on their shelves, the tags on their clothes, the pictures on their walls? If Seymour had a secret online dating profile, it wasn’t for flings; it was to indulge his favorite hobby: judgment. (This was normal, right? To feel this way about your partner of 20-some years? To so casually think things that you know, spoken aloud, would eviscerate him?)

Seymour went on: “All this categorization—art rock, math rock, proto-psych-punk-rock—but how to sum up my beloved’s aesthetic, his most special of specialties? Is there even a word for it?”

“Headphones music,” Lee murmured.

“Whatever that means,” Ellie said.

Lee couldn’t stop himself from expounding, even if the sound of his own voice sickened him. “In the milieu of Dead C or Cecil Taylor or early Amon Düül, whatever.” For the past few years it had been what he focused his collection on: weird jazz, avant rock ’n’ roll, mental asylum music, obscure noise, static dirges, art brut, field recordings of crazed inbred Appalachian folk dances, dance-funk remixes of primal scream therapy, musique concrete, monk chants played backward and layered over swirling psychedelic instrumentals, music to take drugs by, music for theorists and professors and aging rock journalists, music to be impressed by more than enjoyed. It was the music Lee was known for—more than the Sodashoppe Teens, more than Tears in the Birthday Cake. That is, this was the music he was known for as a collector, the dealers at the swap meets and conventions always setting aside their “oddball” stuff for him. He bought it all, practically sight unseen, no matter the cost. In a way, he was trying to keep up with Mickey Gordy. As if there were some sort of competition going between the two; Lee’s entire career was Mickey’s footnote.

In truth, it was music he wasn’t sure he actually liked, but at least it demanded attention. The more abrasive, the better. The more obscure, the more worthwhile. Listening to it was edifying, productive. It increased his knowledge even when it didn’t speak to his soul. Enjoyment was frivolous. Lee had so many records that he could listen to ten a day and die without having heard them all. Once upon a time his true love had been the two-and-a-half-minute pop song: verse chorus verse bridge chorus chorus fade-out. He had an unparalleled collection of 60s and 70s pop LPs and singles with special attention paid to the lesser-known also-rans of the British Invasion as well as American regional garage rock. But he couldn’t bring himself to listen to it anymore. One night a couple years ago, alone in the basement record room of their house in Massachusetts, he got up to select an album and his heart began to pound, he felt like he couldn’t breathe, his head spun. He thought, with a little bit of relief, he was dying. But it was just that he couldn’t decide. There were too many options, he could only hear one thing at a time, how could he decide where to start? He ended up on the floor playing side A of The Ventures Play Tel-Star, the Lonely Bull over and over, trying not to have a panic attack. Since then, he’d taken up his regimen, plotting out in a leather-bound daily planner just what he would listen to each day. He had scheduled his listening sessions into the next year but always wrote in pencil so that he could make last-minute substitutions for intriguing recent acquisitions.

Seymour hooked his arm around him. “The first time I let him take me home, the sex was all right, but what I really wanted was to fiddle with his Sansui 9090.”

Lee wondered if there was a phrase in French to describe the way the cheap weed scent made him nostalgic for the time in his life he’d been the most severely depressed.

Ellie had worked her way through the exotica crate and was re-admiring the Denny album that had first captured her attention. “How much?” she asked.

Lee was about to say that a green sticker meant five dollars, but Seymour cut in: “If you’re going to stare at it like you’re in love with it, just take it.”

“Really?” Ellie tucked the record under her arm. Seymour nodded.

“That was generous,” Lee said, pleased to finally muster up some sarcasm. Since returning to his hometown, midwestern pleasantness had slipped onto him like a straitjacket. “We can definitely afford to just give stuff away.”

“Who cares?” Seymour said. “It’ll play fine but it’s in crummy condition. Should’ve been in the dollar bin, anyway.”

“The dollar bin still costs a dollar,” Lee said in a melody of passive aggression he was mortified to recognize he’d inherited from his mother. An argument, a fight, or at least a bit of bickering was forthcoming, a welcome reprieve from the silent tension that had followed them from Boston to Wichita, though Lee wished he could reschedule it for a more private venue.

Ellie lingered, perhaps as drawn to histrionics as Seymour, perhaps simply too stoned to tell her feet to beat.

“Here, it’s on me.” Seymour produced a crumpled dollar bill and dropped it in Lee’s shirt pocket. “But we should make it two for a dollar.” He grabbed the Sodashoppe Teens album from out of the bin on the floor and presented it to Ellie. “Dealer recommends,” he said and hummed a bit of the melody to “Handclaps in My Heart.”

“Don’t,” Lee said.

Seymour pointed at the Teens’ feather-banged visages. “You know who that is, don’t you?”

Ellie narrowed her near-black eyes.

“Stop, Seymour. Not now.” The last time Lee punched Seymour was in the mosh pit of a Hüsker Dü show in 1985; his restraint since then was perhaps overzealous.

“Well, don’t you recognize him?” Ellie shrugged.

“Kids these days”—Seymour gave Lee some side-eye—“need to familiarize themselves with the canon. See this guy right here? That’s—”

“Seymour.”

“This guy right here is actually—”

“Seymour!”

“Mickey Gordy,” Seymour said. “This is where he got his start.” “Never heard of him,” Ellie said.

“From the Spastics? Cultkill? Babylon Dreamers?”

Lee grabbed a bunch from the dollar bin and shuffled through until he found a copy of Taboo, a classic of easy listening Orientalism, the phony Polynesian birdcalls performed as virtuosically as the vibraphone. “Here.” He put it in Ellie’s hand, trading it for the Sodashoppe Teens, which he deposited in a box of broken stuff headed for disposal. “Arthur Lyman. Right up your alley.”

Ellie studied the volcanic image on the cover for a long moment. “Forget it.” She set both it and Quiet Village on top of a crate. “I only liked this for its look. The fact that you’re trying to get rid of it makes me not want it anymore,” she said.

It took Lee a moment to understand she was referring to the record, not Seymour.

__________________________________

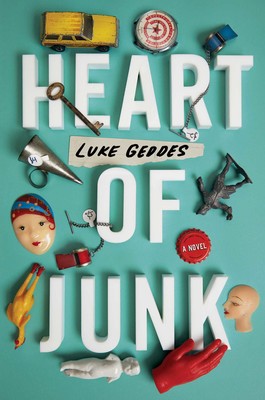

From Heart of Junk by Luke Geddes. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.