She hadn’t cried. She vomited after it was clear that the red-truck kid was not going to come back to life. The vomiting made Andi feel like she herself was a small child. She was surprised by her body’s visceral repulsion to the dead red-truck kid. It was the image of his small, corn-dog-sized thigh that made her vomit. Andi hit Artemis again, this time on Artemis’s shoulder. How long could she get away with hitting Artemis Victor?

*

Bob’s Boxing Palace had been selected for the Daughters of America Cup because of its central location, the fact that it was vaguely in the middle of the American heartland, or was, at least, not near an ocean, and because Bob was the brother of the head of the Women’s Youth Boxing Association, which collected one hundred dollars from each entrant to pay the referees, the judges, and the facility fees and the association officials for their time.

*

Andi had used her lifeguarding money to pay the entry fee, which now seemed like blood money.

*

There was always a qualifying, regional Daughters of America Cup before the national one, so the WYBA collected fees from over one thousand young women, which means that they did make a profit, usually fifty or sixty thousand dollars, and Bob got to take some of that home for having it at his rundown gym.

The difference between Artemis Victor’s and Andi Taylor’s bodies was that Artemis was thicker. The muscles stuck out from her arms and her back like there were ropes under her skin. In Artemis’s forearms there were clear lines of sinew from her wrists to her elbows. Her shoulders were broad, and looked especially large when she crammed them into strapless dresses. During fights she always wore makeup. Artemis wore waterproof mascara and a red stain on her lips.

*

Andi was tall and gangly. She had a cross-country runner’s body. People were always telling her she should try running long distances. She wasn’t interested.

*

Artemis Victor had the archetype of a ponytail. She had so much brown hair it barely fit in one rubber band. When she wasn’t fighting she wore it either on the side or in a big bun on top of her head. Even up, it was still long enough to brush against her shoulders. She always said she was growing it out to cut off and give to a girl with cancer, but she never cut her hair except in small, two-or three-inch trims.

*

The stylists at the salon Artemis goes to never seem to listen. Don’t cut too much, she tells them. I need it long, she says to them. She always leaves the salon feeling like some part of herself has been stolen.

*

Andi Taylor’s hair was so thin that when she braided the whole of it, the braid was as small as her index finger. When her hair got wet it felt slimy. Andi Taylor worried about her hair breaking off when it was really cold out. It had happened once, just with a couple of strands, but she had so little hair that it felt very dramatic, like she had lost something in short supply that she would never get back.

*

The fact of the two girls’ bodies was not lost on Artemis Victor or Andi Taylor or on any of the young women in the Daughters of America tournament. Their bodies were the only tools they had at their disposal. This wasn’t lacrosse or tennis. There were no rackets. They had their arms and their legs and their headgear-clad heads and their glove-covered hands, although the gloves and the headgear were just there as protective measures, to make sure they didn’t kill each other. The gloves and the headgear weren’t something they needed to perform the skill they had practiced, though they did, in their separate states, in their separate gyms, all practice with gloves and headgear. The gloves and the headgear were like clothing. One could box with them, or without them, just as one could, technically, swim naked or in a suit.

*

Andi Taylor and Artemis Victor looked at each other’s bodies under the roof of Bob’s Boxing Palace and tried to figure out how they could make their fists touch each other’s faces. This was the first match of the tournament, the semifinalist round. If you lost, you were out. There was no back door in the Daughters of America.

*

Andi advanced towards Artemis with her right foot out in front, dragging her left leg behind her. It was an inelegant, inefficient strut that got her where she needed to go, just not very prettily. Andi had never been concerned with the brokenness of her form. She didn’t know about the many problems that could come with advancing so off-balance. Andi opened so much of her right side up to her opponent this way. She was walking like a crab. It was a stupid way to box. It was weird. As in, it looked weird to Artemis. None of Artemis’s sisters boxed like this. Andi was tremendously off-balance, so Artemis swung at her. Artemis’s glove touched Andi’s chest. The referee called the hit.

*

The way Andi’s body recovered from the blow was even stranger than her off-kilter advance forward. She had leaned into it, which seemed somewhat impossible. But Andi had, in fact, seen the hit coming, and, though too late to move her whole body, she had been able to move back, slightly, out of the way of the full impact of Artemis’s fist.

*

Andi saw Artemis’s glove hit her chest more than she felt it. She saw the red fabric of the glove move under her eyes and in between her shoulders. It was like she was flying over a red piece of fabric. Andi was on top of the red ocean. She pulled away and started her advance towards Artemis again.

*

The difference between them as fighters was greater than the difference between them as people. Artemis’s form was polished and calculated. Andi hit carelessly. Her hands moved slowly, but in strange directions.

*

There is a glorification, in the world outside of boxing, of desperation and wildness while fighting— his notion that desire and scrappiness can and will conquer experience. No boxing coach has ever asked their athlete to be more desperate. Control and restraint are much more valuable than wild punches.

*

Andi wasn’t sure why the sight of her father’s dead body had upset her so much less than the sight of the dead red-truck kid. It could have been because the boy’s body was evidence of an unlived life. Perhaps it was also because Andi felt she had killed the boy. Had Andi killed the boy? Both bodies had been obvious surprises. Her father had died on the couch watching television. He had lived in an apartment, divorced from Andi’s mother, and lived alone. When Andi found her father it was just her and the dead version of him, her alone with the corpse upon entry. She thought of them there together, her entering the apartment and her father having missed the last hour, his favorite hour, of television, already dead before the episode had even had a chance to begin.

*

The fact that Andi had felt two corpses (Artemis had felt zero) mattered zero while they were trying to hit each other’s bodies. They were both young girls who grew up being treated as young women, which unified their lived experiences more greatly than any family (or witnessed) tragedy. It was not as if women’s boxing was, or ever had, or ever would be something respected enough to put every ounce of your energy into. The practice took its toll on both Artemis’s and Andi’s bodies. The sweat that hung in between Andi’s forehead and her headgear gave her acne that she had to cover up with foundation. She looked terrible in bangs, but she cut her hair with bangs anyway, to hide the way the headgear plastic made her break out into deep, subterranean zits. She’d gotten a staph infection in one of the zits once, from touching her face after touching some of the lifting equipment at the gym where she practiced. The bacteria had rotted a pea-sized hole into her forehead for a full week before her mother insisted she go to the doctor. The doctor had to shoot Andi up with extra-strength penicillin and then the staph infection had scabbed over, leaving what looked like a dead bug on her forehead for nearly six weeks.

And not to mention the broken bones they both have, mostly in their fingers. Both Artemis and Andi have broken their fists loads of times, but Artemis’s fists have been broken a dozen more times than Andi’s, and, though Artemis doesn’t know it now, this additional dozen number of finger breakings has already pushed the fragility that is her human hand over the bridge and into the realm of permanently damaged. When Artemis is sixty she won’t be able to hold a cup of tea.

__________________________________

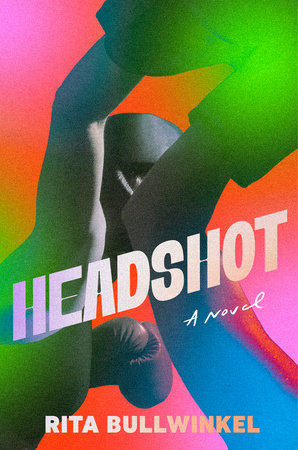

From From Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Rita Bullwinkel.