Haunted by the Question: What It Means To “Become” a Writer

Efrén Ordóñez Garza on Writing as Practice, Lifestyle, and Identity

In “Leopoldo (His Labors),” Augusto Monterroso tells the story of a man seen as a writer by everyone but who never finishes any of the stories he sets out to write. Leopoldo Ralón spends his days in the public library, researching, reading, and writing endless notes for a short story seven years in the making.

His idea is simple: a city dog is moved to a farm and, at some point, meets a porcupine, whom he must fight probably to death. To write a realistic battle, he reads and takes notes on all there is about the behavior of dogs, their smarts—it turns out they are not the brightest—and their physical capabilities, about life on a farm, the dynamic between humans and animals.

However, he is unable to scheme the ideal ending. He thinks that if the dog wins the fight, his not-yet-real readers could see it as a statement on the superiority of the city, of progress and technology, over the quieter and perhaps outmoded rural life. On the other hand, if the porcupine wins the fight, he would probably be seen as a detractor of technological advancement.

The man goes back and forth, distracted in the meantime by ideas for other stories—for which he also takes notes—and by studying, observing, people coming in and out of the building. Of course, he never finishes the story: he is doomed to spend his time doing research and taking notes. Monterroso’s story could go on forever because he condemns his character to perpetually postpone his work, to dally ad infinitum.

*

I first heard about Monterroso and this story from Guillermo, a friend I met working at a call center in Monterrey and who was a few years older than me, a Spanish major at the time, and the only person I knew who read books. Back then, nineteen, almost twenty years old, my life goal was to become a filmmaker, so “Memo” would share some of his books and talk to me about literature to shape me into a more cultured director. I’d listen because he was eloquent, but also because he looked the part: thick black paste glasses and a traced beard running along his jawline. He was a “writer.”

Two years later, after reading everything he recommended—“real books,” he’d call them—I spent a year in Seville, Spain, as a laptopless exchange student, waiting tables to pay rent, watching movies for hours in the dark, empty, university film room, and devouring as many books as I could, guided now by Memo’s emails and everything on the “syllabus” at the school of Roberto Bolaño, whose work had just been introduced to me. I wasn’t going out much. I was reading. It was there where I wrote my first short story, as an experiment, under the influence of the Chilean writer, who has motivated so many young aspiring writers.

When I came back to Mexico, I showed my story to Memo. After a few days, he invited me to his apartment and solemnly lauded my attempt to write fiction, then encouraged me to drop the celluloid dreams and begin to write in prose. “You can direct films as vanity projects after you publish some books, like Paul Auster did.” The joke clearly tells itself, but I believed him and followed his direction.

There is a difference between writing as identity and writing as verb, even as craft.

After the switch in aspirations, Memo and I set out to workshop our stories one on one. That’s when we talked about Leopoldo, as if he were a real person, a ghost rather, always lingering above us, a menace we were trying to avoid or a lesson to be learned, as we sat in front of each other some evenings after school and read out loud in his studio, drinking coffee and highlighting our stories in bright green, pink, and blue, with the grayish undertones of the evening lights in downtown Monterrey coming through the window.

A year after he decided for me, I had finished a few short stories that won some small contests, but my friend found ways to either postpone his writing or avoid sharing it with me, although he did tell me that he was taking notes, reading more, getting ready to put his stories together. I had passed the test of not becoming the doomed character in the Monterroso story.

My stories were far—miles away—from perfect, but I was spitting them out to the world with the confidence boasted only by the naïve. I was writing, reading, and learning what a writer is supposed to be. I saw myself as one and I promised myself and Memo that I would never become a Leopoldo. He was not a writer. The character was a procrastinator, ambivalent, afraid even.

But in a way I did end up becoming a Leopoldo. I have spent years now questioning what the writing life is supposed to be, haunted by the ghost of that character, by the words of the writers who were supposed to teach me the way, but mostly by the fact that maybe I was not—am not—a writer, but rather someone who writes or has been writing for some time and was swept away by the encouragement of others who maybe were not right.

When one decides at a young age to follow in the romantic footsteps of the writers exiled in Europe in their twenties, who walked and lived and read and wrote in absolute precarity, sheltered by the baroque and the gothic, wandering, cigarette tight on their lips, on cobbled streets flanked by inns and taverns and the sound of bull sessions in cafés at dusk, one should also know that the life choices derived from the fantasy will bite back. But no one tells you that.

A couple of years ago I started thinking that maybe I would’ve been happier becoming something else—or nothing at all—and that after all this time, the answer to a question the journalist Mónica Maristain asked Roberto Bolaño in the most famous interview of him out there, published first by Playboy magazine and subsequently in book form, an interview I kept going back to for years, but then kept in various boxes as I moved between Monterrey and Mexico City, finally made sense.

Mónica Maristain: Will Lautaro (Bolaño’s son) become a writer?

Roberto Bolaño: I wish him to be happy. So, I hope he becomes something else. Perhaps an airline pilot, or a plastic surgeon, maybe an editor.

A few months ago, during a phone session with my psychoanalyst, who lives in Mexico while I am now living in New York, he asked me a question he had been asking in different ways for several weeks: Why do you want to be a writer? He didn’t ask why I wanted to keep writing for a living or editing or turning other people’s manuscripts into books, or palpable objects, which is what I do. He asked why I wanted to be a writer.

In the past twenty years I had become a writer—or at least I thought I did—then stopped being one, at least in my head, and recently the topic during our sessions had shifted from my newly discovered and late coming homesickness to the crisis of not being able to finish a book of my own in years. I was browsing inside a Bed, Bath & Beyond on the Upper West Side, the spot I chose to talk with my psychologist because I thought I could save some time—though, to be fair, that store does bring me peace. I didn’t know how to answer. I had several answers that almost came out but was scared to pick one.

In previous sessions we had talked about a change in direction, the possibility of reinventing myself, of starting over here in New York City. I had suggested culinary school (he scorned the idea, which was unprofessional), doing improv (this one he said could help me go back to the child actor in me), or maybe an internship at a network, to start from the bottom, which was okay, but boring. The sometimes stressful, but also comforting and convenient long silences forced by my analyst, gave me a moment to mull it over, between aisles filled with aesthetically pleasing plastic containers. “Maybe I was never supposed to become a writer,” I finally responded two aisles over, while holding a wooden spatula and thinking that I needed one.

*

Leopoldo Ralón didn’t decide he was going to become a writer. He was the victim of circumstance. He grew up in a building where a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer, and a voracious reader of poetry would sit together to talk at the end of the day. That, in a way, made him feel like an intellectual himself. When he was seventeen, he fell in love with film and the landlord’s daughter and was far from seeing himself as creative.

One day, he went out with a book to sell under his arm. He wanted the money to buy a movie ticket. One of his neighbors, don Jacinto, sees him with it and young Leopoldo feels embarrassed because he knows the man is an avid reader, and anticipates a conversation about it. “So, you like literature, little friend?” asks don Jacinto. Leopoldo says he does. “And do you write?” The teenager says “yes,” and keeps saying yes to everything. He even says he writes all the time. “And what is it that you write? Poetry? Short stories?” Stories, he says. “Well, I’d like to read some of them,” don Jacinto says. Leopoldo is prompt to say that they’re all bad, that he’s just starting. “Don’t be modest. I’ve been watching you for some time now, and I knew you were a writer. I am sure you have talent.” Leopoldo feels compromised and tells him he’ll share one as soon as he finishes it. “Tonight, at dinner, I am telling everyone that we have an unknown writer among us!” And thus, don Jacinto sentences him.

After that conversation, Leopoldo feels the pressure of being seen as something he never thought he was or could be, but he also believes him, in a way, so he begins to think about possible stories to write, to read books, and, in other words, to become the writer he was told he already was. The man told him that he had talent “for sure.” But did he? In any case, that’s how Leopoldo’s “calling” was born, writes Monterroso.

*

I also did not decide I was going to become a writer. I was also a victim of circumstance. Before going to college, I wanted to become a filmmaker, so I enrolled in a communications program—there are two main film schools in Mexico, both far from my hometown, and it’s almost impossible to get in—and aimed mainly at the film and media courses in the program.

In my first semester, in a core psychology course, the professor called me aside after class, handed me a graded essay, looked me in the eye, and said: “You’re a very good writer.” She looked confident in what she was saying. I respected her. Before that, I had never thought about writing as craft, as a trade, or even as a means of expression. I was reading literature in small doses, so I was still safe from it, and her sentence was flattering. Comments like this, true or not, can veer someone’s life in a certain direction. People should be very careful when they say things like this. But she was not the only culprit.

A couple of semesters later, while in Seville, when I developed an interest in screenwriting after reading a few books about film theory but was feeling insecure about my path, I emailed another professor back in Mexico, the film expert, with questions about the idea of writing for the screen before jumping into directing. He wrote back:

“Honestly, I think you have what it takes. You have a good sense of rhythm, of conflict management and a good descriptive style. You are very “visual” and that is of essence. Your use of words allows you to visualize what you intend to achieve on screen. I wouldn’t hesitate one bit to tap into screenwriting. You can call yourself a writer.”

He realized then that, to become a writer, it wasn’t enough to put pen to paper and scribble away.

I started reading books about screenwriting, read dozens of scripts, and fell in love with the story of how Sofia Coppola was stuck after page ten when she was writing the script for Lost in Translation, which became one of my favorites and which I have seen maybe a hundred times by now. I was moved by the image of her staring back at the screen, at the scene where Charlotte meets Bob in the bar at the Hyatt and they talk about their respective marriages.

But those screenwriting books sent me back to the page, made me want to write elaborate synopses, which rapidly morphed into an interest in literary fiction and into the experiment I tried that year and later showed Memo, who pushed me into the abyss. Perhaps Leopoldo and I had an itch, true, but I’ve also had others: when I was eighteen, I bought a guitar with a summer’s worth of savings and never learned to play it.

Years before that I tried painting because my grandfather was a painter and my mother wanted me to become one. It didn’t happen. When I was ten, I auditioned to play the protagonist in a professional play. I didn’t get it. Between my professors and Memo’s push, I accepted the idea of what I was supposed to do, but who knows if Leopoldo and I would have decided to become writers if someone hadn’t told us that we were before we had even questioned who we were.

Neither one of us was born to do it, at least not in the way bell hooks describes it in the opening of her book Wounds of Passion, a writing life, when she says that from the age of ten, she dreamed of being a writer, seeing books as ecstasy, imagining writing words that would have the same effect on other people. Perhaps if I had gotten the part when I was also ten, I would’ve been the one sitting with Jimmy Kimmel a few weeks ago and not Diego Luna.

But what does it mean to “become” a writer? If we take the affirmation that whoever writes is a writer as true, I wouldn’t be writing this essay, and probably would’ve never questioned myself. But there is a difference between writing as identity and writing as verb, even as craft. Here’s where the conflict lies. I’ve been punching keys and stringing words together for a living for about fifteen years now, and that is why on social media I identify myself as a “keypuncher,” which is a way for me to undermine, consciously and obnoxiously, what I do for a living, but also because after some time, the approach I took towards writing was that of craft and not of a calling, much less my identity.

My grandfather was a visual artist, a painter, but he painted with the rigor and attitude of the working man: woke up at six, dressed in a denim shirt and jeans, wore thick brown boots, the stamp of a factory worker from the forties with a nine to five shift at the line. Even though he read many books about art, and was deeply committed to painting, there was no bohemian aspect to his life. He decided to take on painting as a full-time job in 1957, with two kids and three more on the way. Art was a way to support his family. There were no late nights, no manifestos, rebellious art, or tumultuous “Europe years.”

He became a painter in the sense that he was a man who painted every day, almost as if his work was a trade. This had to do with his context, which is mine as well, of living in an industrial city whose entire identity is based on work, business, entrepreneurship, and the need to keep going onward and upward, almost despising lateral growth. We are taught that being productive and handling yourself as if you’re always about to start your own business is a way of life. Even his oldest daughter, aunt Silvia, who also became a painter, told me once when I met with her to ask her for advice in the event that I also chose to follow in the family’s line of work, that if that ever happened, the first thing I needed to know was that painting was not a way out of a job, that to make a living I’d have to stand in front of the canvas for eight hours a day, five or even six days a week.

I remember that the first time I published a short review of César Aira’s novel The Proof in a small cultural magazine printed in newspaper and that I still have, when I was in college, my father made a “pay me” gesture with his hand to ask me how much the gig paid after I told him. It didn’t pay. Not that a writer should work for free, but at that time it was not the point. This malady of entrepreneurship has been a problem that shows up in everything I’ve written, the counterweight to the ideal of the iconoclast artist, but it has also been what has kept me afloat, out of debt.

At some point in my life, I became a writer in the sense that I wrote as if I also had to punch a card at the beginning and the end of each day. Mechanical. Fixing a price per page or per word. But that is not how it began. When I first started, I felt that writing was an identity, a way of existing in the world, or at least that is what I learned while I was gradually being infected with literature.

The Spanish writer Enrique Vila-Matas, through his novels and short essays, has reflected extensively on the idea of the literary writer, and it is from him that I learned the concept of “literature sickness” in my early twenties, just after my only writer friend at the time, Memo—who was not a writer—had pushed me into the unknown. Vila-Matas writes literature-sick characters, like Montano, in his novel Montano’s Malady, who stops writing and makes the decision to incarnate Literature, to become Literature, to exist only as Literature. But Vila-Matas also questions his own identity.

In his essay “To Write is to Quit Being a Writer,” he writes that he became a writer because 1) he wanted to be free and not have to go to the office every morning, and 2) because when he was sixteen, he saw and was blown away by the character of Marcello Mastroianni in Antonioni’s La Notte, as a writer dating a woman named Lidia, played by Jeanne Moreau, and he wanted both things. His first approach to the idea of the writer was not through reading, the act of writing, the need to think, or even an infection of literature—although the pull towards the idea based on the movie is extremely literary—but rather over the persona of “the Writer.” The aura. Around that time, when his father asked him what he wanted to do with his life, he said: “I want to be Malraux.” He did not say he wanted to write like André Malraux, or even to be like him, but to be him. His father replied: “Being Malraux is not a career choice. They don’t teach people to be Malraux in any university.” On his own way, even before he started writing, he felt the need to incarnate Literature.

However, later in the essay, he writes that at some point he realized that to be a writer, one must learn how to write well, and in most cases, to write at least “very well.” And that is hard. It also requires an infinite amount of patience. He then goes on to the famous and often tweaked Oscar Wilde quote on the comma to explain why the writer, to write well, must give oneself to the life of the artist, because for him and many others, achieving that requires much more than a manual. But Enrique Vila-Matas understood he had to engage in the act of writing first.

*

After Leopoldo was told that he was or looked like a writer he started taking notes. He would scheme plots for films, plays, for mystery, noir, and even romance novels. He thought about form. He would reflect on dialogue, or stories stripped of dialogue, epistolary novels or those written as a diary. Even though he wrote all these thoughts on paper, Augusto Monterroso writes: “The moment of putting pen to paper kept moving farther away as years went by.”

Notebooks are not here seen as a literary form, even though he was extraordinary at note taking, which could very well be a literary genre. In fact, as I write his, I have Chekhov’s Notebook in front of me, a book I pulled out of my bookshelves after I decided to write an essay around a non-writer who is doomed to write notes forever. But as we know, Anton Chekhov’s notes did become finished works of art. Leopoldo would take all sorts of data in and archive them, he would observe and reflect on the nuances of daily life, but never could get past his notes. He was never satisfied with his ideas, so he’d never say something was finished.

However, later in his twenties, his friends saw him as a writer, there was no doubt about that. Even his wife married him seduced by the idea of being with a writer. She’d never seen anything published, but she had seen the countless boxes filled with note cards, and probably had to listen to his ideas and views on style and recently published books before going to bed.

After some time developing his writing persona, Leopoldo decided to prove himself a writer. One morning he woke up inspired, with the splendid idea of writing a fight between a dog and a porcupine. The first attempts were complicated. He realized that executing his ideas, translating his notes into a literary text, was not as easy. Perhaps if he had access to Wisława Szymborska’s anonymous column in the Polish journal Literary Life, he would’ve gotten cruel but honest advice like that she gave.

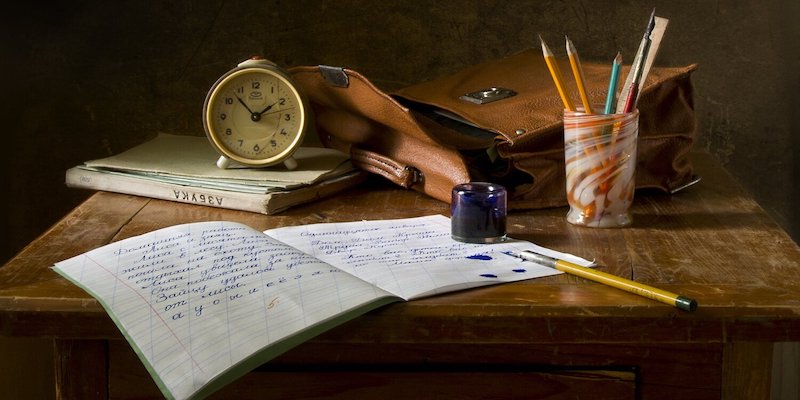

But he didn’t, so he stopped and read books about dogs until he felt ready. When he finally felt apt, he prepared his writing space, his room. He had a desk, enough paper, a fountain pen, even a nineteenth-century green shade to feel comfortable under the artificial light. He demanded silence in his house, looked at the ceiling, sighed, and started writing. He prepared a room of his own, created a space for what he thought was necessary for a writer.

The only problem with being a voracious reader of literature is that the more you read, the more likely you are to catch it as a disease.

What comes after in the story are Leopoldo’s blunders. He wasn’t good and he knew it because he was also a critical reader. He realized then that, to become a writer, it wasn’t enough to put pen to paper and scribble away. He understood that to be a writer one had to not only write, but to write at least “very well.”

*

Augusto Monterroso and Enrique Vila-Matas merged the writer as character and the writing as craft. To learn how to do it one has to read. Not guides or manuals, but great writers. The only problem with being a voracious reader of literature is that the more you read, the more likely you are to catch it as a disease. If you’re young, you want to emulate the lives of people who led romantic, idealized lives for the sake of art, and you could start believing in the self as a literary character, especially if that self flirts with the idea of becoming a writer. You might feel compelled to start acting like one and see yourself in the writers written by writers. If you read certain books, you might think that you need to become a starving flâneur or flâneuse, observing, always carrying a book, and getting lost in labyrinthine cities.

Enrique Vila-Matas, as many others, covers the act of writing with a literary shroud, since he says that to write extraordinarily well, he had to renounce playing the part and to chain himself to a “noble but relentless master.” Writing as an action, a craft, but also as a way of life in service of virtuosity. He probably learned this as Truman Capote did when he said, “Writing stopped being fun when I discovered the difference between good writing and bad and, even more terrifying, the difference between it and true art. And after that, the whip came down.”

Becoming a writer like this could feel like a death sentence. It perpetuates the myth of the artist as a martyr. Marguerite Duras wrote that in her life she was “more of a writer than someone who lives.” I adore Duras, reading her is exhilarating, but this idea of writing in opposition to living can also be suffocating. And yet it is true that for many literary writers there is a separation between those who live and those who write. Franz Kafka wrote to Felice Bauer that he did not have a tendency towards literature, but he was Literature, an idea many writers have taken to heart. There is a problem for some people when they make the connection between the writing self and the mere act of writing. It’s the approach. Why does becoming a writer mean to be Literature as Kafka said? Why does becoming an artist mean suffering at all? Renouncing the self?

The word suffering now brings to mind one of my favorite books, and a huge part in my literary education, Hunger, the first novel by Knut Hamsun, which is based on the life of the author before he became one of Norway’s main literary figures. As I remember the book and take it from the bookshelf to my desk, I open it and read the introduction by Paul Auster, with the title: “The Art of Hunger,” referring both to the title of the novel and to the heroisms perhaps of starving to death while walking the city thinking about writing but not writing. Now I know that if I had the chance to go back in time, I’d never recommend a book of a delusional young writer driven by starvation to my younger self. But this enthusiasm for precarity has survived and exists in our digital era, often making artists accept instability in the name of their calling.

For many years I associated the idea of the writer with that of living as a writer instead of being someone who lives and writes. And although it never fully took over, meaning I never became a poète maudit, even as I read and reread the Savage Detectives by Bolaño and the adventures of his Visceral Realists, I had a soft spot for phrases like this one, which Mario Santiago, Bolaño’s best friend from his Mexico days, said and which the Chilean repeated in an interview: “If I must live, it shall be rudderless and in delirium.” Si he de vivir, que sea sin timón y en el delirio. There was some of that ethos behind my life in my twenties and part of my thirties.

My life choices were marked by the ideas of these writers. I never looked for nor kept an office job (thank you, Vila-Matas), which meant that I had to be creative and find ways to get by. I worked as a freelance translator and spent many years chasing after payments, constantly logging into my bank’s website to see if at least a couple of zeros were added, delaying plans and trips until that happened. I spent the little money I had on books. When I moved to Spain as an exchange student, I thought I might drop out of college and stay there and probably rent a mansard and live my life chain-smoking, drinking coffee, and reading in parks. I was working, and going to and then skipping class, but mostly I was walking, reading, and watching films.

And yes, I did write. Then, a now unimportant romantic outburst made me move back home. I tried it for a second time, two years later, and repeated the performance, now in film school in Madrid, until I had to move back again. I moved to Mexico City and tried to make it there as a writer, not once, but three times. By the third time no one even knew I was trying to be a writer.

But to suffer this sentence, to get lost in the depths of human existence, especially if this happens with the aid of books, one needs time. Becoming a writer is contradictory with this moment in history, or at least the past hundred or so years, when productivity became the norm. And here’s something I couldn’t understand in my early twenties. There are two opposite figures of the writer: the starving artist, like Bolaño, who spent his life being “poor as a rat,” an expression he wrote often and that stuck with me, a condition that took its toll later in his life as he died in his early fifties, then, the wealthy writer who had time to think and write, and here I think of the Argentinian posse of Borges, Bioy, and Victoria and Silvina Ocampo, who either had money to spend time living as writers or were part of that social class.

Or how about Alfonso Reyes, the most important writer from Monterrey? He died over sixty years ago, and was the son of Bernardo Reyes, the state’s governor, a military man, and at some point a presidential candidate, who could afford paying his son’s lifestyle, which included traveling the world and being appointed Mexico’s ambassador to Argentina, where he met Borges, the Jorge Luis Borges, one of the most revered writers in literature and who referred to Alfonso Reyes as “The greatest prose writer in the Spanish language of any age.” I guess you don’t earn that title by working nine to six and paying bills or climbing out of debt.

There were other Latin American writers who were appointed to embassies and consulates in Europe, an opportunity which gave them time to wander, think, and then write the very same literature that infected me. I’ve read that money doesn’t buy you possessions, it buys time. And time and space are what a writer is always after. That is why a good number of writers I know work as freelancers, to compensate the stability they lack with time to think and write.

Becoming a writer means being in a constant search for time. César Aira wrote: “You can’t write a novel the night before dying. Not even one of the very short novels that I write. I could make them shorter, but it still wouldn’t work. The novel requires an accumulation of time, a succession of different days: without that, it isn’t a novel. What has been written one day must be affirmed the next, not by going back to correct it (which is futile) but by pressing on, supplying the sense that was lacking by advancing resolutely.”

*

Leopoldo was living as a Writer. At least he had the time. Since he was seventeen, he gave all his time to literature. His mind was fixated with it. He was sick with literature. He was a relentless reader, a meticulous writer. He had ideas about writing and writers. “To read is to write too,” said Duras. However, there was a problem: he didn’t like to write. He read, took notes, observed the world, attended book events, criticized poor writing in newspapers, surrounded himself with writers, was thinking, speaking, eating, and sleeping as a writer. But he was terrified every time he had pen in hand. Although he wanted to become a famous writer, he couldn’t write, hiding behind the typical excuses: you must live first, you need to read everything, Cervantes wrote Don Quixote at an old age.

Among the many obstacles that Leopoldo set for himself was not just the obsession with detail and truthfulness. After all, there is only so much one can read about dogs. In the years he spends taking notes and reading, he also observes. He sees a lot and almost everything has potential for a story. He says that bars, streets, offices are all spaces where subjects and topics for stories can be found. He is convinced that a writer can write about anything.

Naturally, he would deviate from his dog and porcupine story to scheme a story for the future and write preliminary notes. Whenever he doubted his main story, it was easy for him to hide behind the possibility of other stories. His own writing keeps getting pushed back. But also, his memories: every time he tries to go back and remember something about himself, he gets distracted by something he sees and immediately turns into an idea—and subsequent notes—for a short story.

But Leopoldo manages to write over one hundred pages of the story of the dog and the porcupine, and that is after shredding some fifty pages. He was obsessed with writing a perfect story, so he dwelled on ideas of time and space—he spent around six months reading only about this—and the relationships between humans and animals. His vision became so complex, so deep, that it seemed that this simple topic was expanding beyond his means. But he persisted. He dreamt of writing a story in the same category as Moby Dick, In Search of Lost Time, or The Human Comedy. Two more years went by.

When we “find” him, Monterroso writes, Leopoldo has changed his mind. When this story begins, the character has shifted his views on what a masterpiece should be. He now is an advocate for brevity. This is another trait that makes Leopoldo a writer. We must assume that during these years, he not only reads about dogs, but he keeps reading literature and about literature and at some point, opts for synthesis. It’s like he goes from Charlotte Brontë to Samantha Schweblin.

*

At some point in my writing life, after learning some lessons the hard way, I was cured. I wasn’t sick with literature. Or maybe I grew out of it. It happened gradually, then suddenly. I knew that it meant that the problems of everyday life had collided with idea of the literary life, that my entrepreneurial upbringing and the influence of my childhood friends had finally clashed with my literary education and the writer friends I had. It started after my first novel came out.

The whole process, from conception to heartbreak, was quite literary: it started with a recurring dream, a single terrifying image of a garbage truck under a leaden sky, ashes falling over its headlights, a decaying cadaver in front. After a few weeks, or maybe months, I turned the scene into a few pages for what I assumed was going straight to short story form. I had twenty-three pages with no ending, already too long. I remember meeting with Memo at a diner to drink watery refill coffee and he gave me his feedback. I don’t remember what he told me, but after that afternoon we agreed that I had a novel in my hands and that it was best to try to find it.

Sometime after that, I submitted it as a proposal for a grant, got it, and spent the next eighteen months writing from five to eight in the morning, before going to my part-time job as a high school teacher. I was thirty years old, and it felt like the culmination of the process of becoming a writer as I understood it, an ending to a decade of maturation. The book was not going to be my best, I knew that much. That is why, not expecting a lot, I submitted it to the state’s literary prize on the very last day. It won, which meant someone saw me as a writer, and that validated the positive reinforcement from my college professors, but also of my life choices: working as a freelance translator to find time to read, teaching literature part time, moving to Mexico City to try to insert myself in the literary world, to become, but then coming back to Monterrey in defeat with plenty of miles walked, many more pages read, but nothing else. In short, every single decision made to live a life devoted to an idea that someone sold me.

We can reduce the writer to a verb, to a set of physical traits, but I know it goes beyond that.

But the novel never found its readers. In the start of his essay about letting go of the idea of the Writer, Vila-Matas wrote that whenever people asked him why he wrote, his first answer was always: “To be read.” We write to be read, a concept that changes with time and is different for everyone. To be read is to be seen and to be seen, to exist. I had realistic expectations and never assumed I’d find thousands of readers, but all the years carrying the disease, working on not just trying to write well, but to write “very well,” were met with indifference.

Not that I had managed to write well or thought I was close to one of my literary teachers, but I was trying. Hard. The book couldn’t find the press—I think I did one interview. It had no mysterious aura, there were no critics celebrating nor destroying the novel. Even daring writers who are more concerned with the form, and experimentation, like Kate Zambreno, whom I have been reading furiously, obsessively, worry about visibility, as she writes in her “Appendix C: Translations of the Uncanny,” when she talks about the topics she complains about in her correspondence with her friend, the writer Sofia Samatar: “…the invisibility of our new books, or the nature of their visibility, the alienating or non-event publishing can feel like.” I felt the same. It was nothingness. And then I stopped. There was silence. This is when the real “Leopoldization” began.

The concept of not writing is not always linked to the typical writer’s block. A person suffering from the latter wants to write, suffers from not doing it, or at least struggles with this. But what about those who choose not to do it? To go silent. That reminds me again of Vila-Matas and his book Bartleby & Co., part memoir, part essay, and novel. The book takes its title from Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street,” about a clerk who always refuses to do any task with the famous words: “I would prefer not to.” In Vila-Matas’s book, he reflects on the lives of writers who were sick with literature, like Robert Walser, Robert Musil, Arthur Rimbaud, Marcel Duchamp, Herman Melville, and J. D. Salinger, but nonetheless decided to stop writing.

My beloved Kate Zambreno says that recently she realized that there are more important things for her than to write, and she finds herself questioning the necessity of writing more books. I have thought about that too. We need to read; hence, we need writers, but sometimes I wish I’d spent more time reading and less time writing. It is clear to me that reading is one of those more important things.

But there are many reasons why someone would choose not to make art. Someone could stop because they just lose interest in the craft, or maybe it is not a choice, but life gets in the way, something that historically happened to women and has been a recurring theme in their writing, as Virginia Woolf describes in A Room of One’s Own, where she writes about the need for time and space and the injustice of women not getting it. I think about this, and I have a hard time entertaining the idea of these men having the privilege of choosing not to write.

The last time I was able to finish a book penned by me was in 2014. My first novel came out in 2015 and then again in 2017; albeit with some editing, it was basically the same book. Back then, I thought that it would be the first of several to come, at what rate I did not know, but it came out just when I received another grant to write my second one, a book that I did not finish, instead handing in a bulk of pages filled with an incoherent, fractured, mimicry of a novel.

I was living in Mexico City for a third time by then. I had started a publishing house and moved there to try to make it work. The non-event of my first book had led me to think that perhaps I was not a writer after all, not a good one, that I never learned how to write at least “very well.” I found myself too deep into the writing life, the book life, to get out, start over. I wasn’t even sure if I liked it anymore. There’s a line that I read from my aunt Silvia in an interview many years ago and that keeps coming back to me: “Painting is the only thing I like to do, and sometimes I don’t really like it. But then again, it’s the only thing I know how to do.” That’s how I felt back then.

Leopoldo had his notes to excuse himself from being a writer. Perhaps he was such a good, critical reader, a smart observer of the world, that he knew deep down that he had no talent. He was smart. He could’ve been something else, maybe a book critic, a publisher, a businessman with a sensitive, artistic side. But he persisted. Someone had told him he was a writer, he bought it, and after many years he could not get out of it. He had to keep going, taking notes, observing the world, reading about dogs, about life, other authors.

I also had my notes. I too felt as if I couldn’t turn back and, faithful to my context, had to keep going forward. Perhaps I was not a very good writer, one that would be sitting at the table with Enrique Vila-Matas and Marguerite Duras in Paris, but I could punch keys for a living, use the character I had created and at least make something out of it. I stopped writing for myself and started writing for other people.

The first two books were easy: first a user’s guide to dating, “authored” by a celebrated YouTuber in Mexico with almost six million followers, in which I managed to sneak in some of my teenage experiences, some internal jokes I had with a few friends, and find some solace in that. The second one was a humorous history book that was supposed to tell the story of Mexico, this one “authored” by another social media star.

I have always been amazed by the wit of comedians and see myself as one of those people who secretly dreams of joining the cast or at least the writer’s room in Saturday Night Live. But here I had to spend hours absorbing somebody else’s sense of humor. I wrote jokes pretending to be another person, with my name nowhere to be found. At least the experiences gave me the right to call myself a ghostwriter.

At some point during those years, while having coffee at a Gandhi bookstore in the Coyoacán neighborhood with one of my writer friends, Mark Haber, we were complaining about our day jobs and how they interfered with our writing lives, as understood from the romantic ideas that had infected our minds. He told me that I was “living the life” because I was a writer for pay, and I was making a living out of writing books. I said he was the one who had it made because he worked at a bookstore and had access to books and presentations. The truth is that we both were miserable.

Over the past six years I have written twenty books and even the script for a concert based on the life of a popular rockstar. Whenever I spend months writing a book or half-writing a book I think about Leopoldo. I remember how he would deviate from the dog and porcupine story to write extensive notes on a story about a doctor, plotting it almost in its entirety but never writing it, even after congratulating himself and thinking that it would make a wonderful story. Why is it that in all these years, I haven’t been able to write a single short story?

After years of thinking about my conversation with Mark, I wonder if I have been writing as a Writer or as a person who writes professionally, a scribe, a copyist. I don’t know if a writer is just someone who writes. The word writer carries a lot of meaning and can’t be taken lightly. Once, Guillermo Arriaga, an author of a few books who is best known for the screenplays of Babel or 21 Grams, was asked about the adage “A picture is worth a thousand words.” He was categorical in his answer: “I hate clichés. Tell me, how many images would you need to show me the meaning of love?” We can reduce the writer to a verb, to a set of physical traits, but I know it goes beyond that.

Quite possibly I too will forever be trying to discover what I would write about if I decided to write.

There was no joy in taking the lives, ideas, and knowledge of others, even if sometimes I managed to sneak in some of my own experiences. There is a difference between a writer and a scribe, and I was—or have been—a scribe. Perhaps this is what Mark did not understand when we had that conversation. In the end, we always want what the other has.

*

The truth is that I have been a Leopoldo for some years now. I have been a Leopoldo who defers his own writing by writing the books of others and taking solace by slipping an idea or social comment here or there on someone else’s pages. During these years I’ve thought a lot about my own fictitious books, I even “write” them in my head: I conceive them, think plot, form, style, language, and how the thing would be read it I ever wrote it.

You could say that the entire book is there, I have it, so is it worth writing? Alfred Hitchcock said in his ten-year-long interview with Francois Truffaut, which was also published as a book, that the most boring part of the filmmaking process for him was the actual making of the movie. When asked why, he said that he already had the entire movie played infinite times in his head, including dialogue, frame by frame, mise en scène. He knew exactly what he wanted and left no room for on set improvisation. He still made the movies. But I am not writing the books.

In Augusto Monterroso’s story, even though Leopoldo had never shown anyone at least a draft or a single page of his writing, one day he reads in a local newspaper the headline: “The Writer Lepoldo Ralón to Publish a Book of Short Stories.” Even this doesn’t move him into action. Monterroso writes that Leopoldo had such a disdain for glory and fame that he did not care about finishing his stories, what’s more, sometimes he doesn’t even start to write them. I don’t share his disdain at all. I’d love to have my picture taken, to talk about my stories or how I see the world. This too has been an ongoing conversation in therapy.

But is there something wrong with being a Leopoldo? In my twenties I was sure I needed to be published to be a writer. I wanted to have a book out by thirty, and I did. Then no one read the book. Should we write to be read or should we write for ourselves? Publication means different things to different people. Borges and Bioy used to say that the only reason they ever published a book was because if they didn’t, they’d be stuck writing the same book over and over until the day they died.

Now I believe that there is nothing wrong with Leopoldo, with the idea of spending one’s life writing in our heads, preparing a masterpiece, observing, like Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet, the copyists—of course they were—who had the time to move to the countryside to talk about everything: arts, science, politics, people. The novel, which was supposed to be the author’s masterpiece, was never finished, and Flaubert claims to have read over one thousand books to write it. To me they were both Writers. They read, were immersed in thought, they had the time, and had probably the necessary observations to have written a few books of their own.

Or how about Tristram Shandy, Vila-Matas’s literary hero who’s a classic antihero, whose life events and opinions (as the title goes) come from his own observing of the world. Perhaps writing is not the act of typing. Perhaps writing is a mere categorization of thought. And if writing is not the act of stringing words together, but to find the time to observe, think, and give some sense to the world, then these eccentrics could very well be writers and Leopoldo would be a minimalistic, hyperabbreviated version of these classic, comedic, literary characters.

Vila-Matas wrote a novel about the process of becoming a writer, Never Any End to Paris, in which he tells the story of the time when he lived in Paris, in a mansard rented to him by Marguerite Duras, who taught him a great deal about writing. After reading Duras’s essays on writing, it is easy to see where Vila-Matas comes from. And speaking of Duras, she did say that “Writing is discovering what we would write about if we decided to write.” Maybe that is what Leopoldo is perpetually doing with his notes. Quite possibly I too will forever be trying to discover what I would write about if I decided to write.

__________________________________

“Was Leopoldo Ralón Supposed to Become a Writer?” by Efrén Ordóñez Garza appears in the latest issue of New England Review.

Efrén Ordóñez Garza

Efrén Ordóñez Garza is a writer from Monterrey, Mexico, living in New York City. He is the author of the novel Humo (NitroPress, 2017), the short story collection Gris infierno (Editorial An.alfa.beta, 2014), and the forthcoming novel Productos desechables (Textofilia, 2023), all written and published in Spanish. He is currently pursuing an MFA in creative writing at The City College of New York.