Hamilton Nolan on How To Write Op-Eds

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

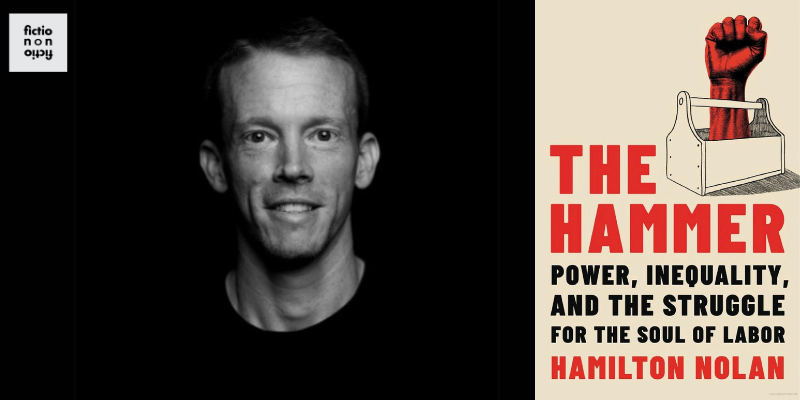

Writer Hamilton Nolan joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V Ganeshananthan to talk about opinion journalism. Nolan, who writes frequently about labor and politics, discusses how and why he entered journalism, the myth of objectivity, and how he views the relationship between activism and journalism. He explains how long it took for him to make money on Substack, reflects on what it means to share an opinion in the current political environment, and considers the importance of unions for writers. Nolan reads from his book, The Hammer: Power, Inequality, and the Struggle for the Soul of Labor.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/. This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Hunter Murray.

*

From the episode:

The Hammer: Power, Inequality, and the Struggle for the Soul of Labor • Your Opinions Can Be Bad But You Still Have to Tell the Truth • Hamilton Nolan | The Guardian • Here’s a New Year’s resolution for Trump’s America: no snitching • Hamilton Nolan – In These Times

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH HAMILTON NOLAN

V.V. Ganeshananthan: I really appreciate all the expertise you’re bringing to bear on this topic today, because I feel like I’ve had a lot of conversations recently with people who are like, ‘I’ve never done this before, I want to get into this,’ and now the environment is really weirder than ever. You’ve just chronicled for us in this great capsule form all of the weirdness of years prior, but now we’re in a moment where opinion journalism has been, in many ways, at the whim of owners and publishers. You mentioned Peter Thiel, and you also wrote about how during the last presidential election cycle, the LA Times didn’t endorse a candidate for the first time in forever, at the direction of the owner. The Washington Post, which also announced it would no longer endorse candidates, recently saw the resignation of longtime opinion editor David Shipley, because Jeff Bezos said that the opinion page would focus on “personal liberties and free markets and would stop publishing pieces opposing those views.” He said that “every day we will be writing about these two pillars.” And I know these are things on which you’re an expert. You spent a year being the public editor at CJR writing about The Washington Post. What is your take on this? And how have you seen opinion journalism, or the space for it, changing over the course of your career?

Hamilton Nolan: Yeah, I would say up front, Jeff Bezos is scum. I mean, anybody who has $100 billion and is a union buster is a scumbag as a baseline, so I think that’s one thing to understand.

Whitney Terrell: I’m glad we got that established.

HN: I think the picture is, I mean, the journalism industry, its economic model has been broken for 50 years plus, 50 to 100 years, journalism minted money. Owning a newspaper was 20 percent plus profit margins every year. And because they made so much money, they had all this stuff that ended up as journalism. They had foreign correspondents, and they had—And one of the things that came with that was an idea of editorial freedom that I think a lot of journalists thought was kind of a state of nature, and ended up to be something that was very much tied to the economic state of the industry. And so as the tech industry and big tech companies have basically broken the economic model of media and have sucked all the money out of media companies that used to go to journalism, everything gets a lot more tenuous, and one of the things that happens is owners start meddling more than they did before. I mean, there’s always been corporate media, a back and forth over what could and could not be said, but to see these billionaire owners just directly sticking their hands into, if not the newsroom, then at least the editorial page and saying what can and cannot be written about, is somewhat unprecedented, at least in my lifetime, for respectable papers like the Washington Post.

So, again, it gets harder when journalism is not making money. So, I mean, one of the core things we need to do, I think, is to move toward public funding of media, which is kind of a big picture answer to this issue, but billionaire owners are going to meddle. And generally, anybody who’s worked for any type of news outlet knows that there’s always an owner who is not a journalist, who has some bright ideas about what he thinks should be written about, and that’s a constant thing that we all deal with in our industry. And you know, Trump is making it worse. He’s making everybody more scared, billionaires are feeling bolder and journalists are feeling weaker, and that’s where we are right now.

VVG: You’re mentioning public media, and Trump just put out an executive order about PBS and NPR… I know Voice of America, where I have some friends who work there—it’s going in the other direction.

HN: No, it’s going fast in the other direction. Yeah, to be clear, everything that needs to be done, we’re going as fast as possible in the opposite direction. So it’s going to get worse before it gets better, no doubt. But I mean, the fundamental problem is the the economic model that supported journalism for the past century is gone now, and nobody’s invented a new one to sustain the kind of journalism that people got used to having when ad money supported our industry.

WT: Now, when you’re talking about journalism, what you mean is the ability to go do reporting, right? To fund a reporter to do a long form story, or several reporters, or a group of reporters, the kind of reporting that The New York Times can do, or the Post can do, but what about—Where I do see money being made, and we talked about this before on the show is—Part of the idea behind the show is to talk about the state of opinion, op-ed journalism, and to talk to readers who want to maybe write their own pieces. How do they do it? What I see, what I listen to, are new entries into the YouTube podcast area that are making money: Meidas Touch Network, I listen to The Bulwark, The Majority Report. These are all YouTube channels in essence, that feel like they aren’t owned. Whatever their model is, I don’t know what their finances look like, but they’re growing in ways that newspapers aren’t. Now, they don’t do reporting, that’s the thing. They have to have the reporting as the baseline stuff that they need to then comment on. I don’t know what you think about that, but the other thing that’s interesting about those networks is that they aren’t trying to divide reporting from opinion, which is the way old newspapers did it, right? Everything they’re doing is opinion, right?

HN: Yeah. I think there’s a couple issues there. I mean, there’s the economic issue that you touched on. You know, I’m somebody who writes a lot of opinion journalism, I’ve done a lot of reporting, I read a lot of opinion but as you said, the reporting is the soil that the opinion grows out of. So we all write opinion stuff, but if nobody’s out there doing the reporting, then that is a civic crisis that is going to affect all of us. So, it’s a lot easier, or it’s a lot less labor intensive, in some ways, to write opinions than to go out and do reporting, and that’s something you find if you’re a freelance journalist, really fast, like you’re incentivized to write opinions more than you are to do reporting, because you’re getting paid the same thing for either one.

But the other issue is, as you said, there was that traditional view of the perspective of God in journalism, where journalists were supposed to pretend as if they were like floating above everything and the voice of neutrality and all that stuff, and there’s been a lot of debates over that stuff in the past 10 years in mainstream journalism and with the rise of online media and a lot of the new voices coming out. There’s definitely a high level of bullshit in the idea that journalists are capable of being neutral, and the idea that you can write about politics, for example, and not have a viewpoint, I think is fundamentally absurd. And so I do think it’s healthy that opinion journalism is established as a thing that exists and is an honorable way to be a journalist.

WT: Yeah, I teach that. I’m like, ‘Look, we’re gonna write opinion journalism here. We’re not gonna try to be neutral.’

HN: Yeah, it always seemed crazy that journalists are supposed to become experts on something and then at the same time have no opinion. I mean, if you become an expert on something, you should be the first one to have an opinion, I always thought.

WT: The interesting thing about this is, in terms of opinion, the old way that you get to write op-eds is you would be a reporter, you would be successful, you would then get kicked up the ladder, maybe into the op-ed room, or if you were a sports reporter, then you would get a column right in that newspaper. Like now you can just say, ‘I have a YouTube channel and here’s my opinion.’ I mean, David Pakman or somebody like that just starts a channel. Or you can have a Substack, which is what you do. I mean, for the past two years, your Substack “How Things Work,” which takes its name from an old Gawker tag for a certain kind of story explaining why the world is the way that it is. I would like you to talk about what that has been like. How successful has that been? I mean, you have an interesting piece on Substack sort of evaluating your two-year anniversary there, but that’s the thing that you can just decide to do. You don’t have to get some editor to decide that you’re good enough to write opinion. You’re writing opinion. You’re taking it directly to an audience.

HN: Yeah, absolutely. It’s very democratic in that way. I should say I think there’s a lot of taste in terms of what kind of writer you want to be, especially if you’re writing journalism, or quasi-journalism, or news, or any type of nonfiction. I personally am inclined to spout off my opinions, I’ve always wanted to write like that. I’ve always preferred to write like that. There are other people who don’t prefer it, and I don’t think there’s a correct answer, but my Substack was really a product, again, partly of the economic collapse of traditional journalism, because I quit my regular job to write my book, and when I came back from writing my book, I was like ‘Time to get another job,’ and there were no jobs, essentially. And so I said, ‘I’m going to start a Substack’. And I had an advantage because I had been in journalism already for 15 years plus, or whatever, and if you already have established a little bit of a name for yourself, it’s obviously easier to launch something independent like that, but my experience has been, over two years, it’s become the equivalent of a full time job for me. I mean, the income is comparable to what I would make as a journalist. I had a friend who had a successful—

WT: That’s kind of amazing. That’s, I mean, that’s cool. Were you surprised?

HN: I really had no idea, you know? It was just, uh, I took a flyer on it and I told myself, when I started it, two things: I said, A, I’m gonna write the same stuff for this that I would write for The Guardian or anywhere else, like, it’s not going to be my musings. A lot of people, you see their Substack is like, musings on blah, blah, blah. Nobody wants to read my musings. I was like, ‘I’m going to write the same essays I would write for a magazine or anything else, and I’m going to do it like a job, and I’m going to do it for a year and see how it goes.’ So, I did it regularly. I didn’t get lazy and stop doing it, and it paid off. I keep it free, anybody can read it, and I just ask people to pay to subscribe if they like it and if they can. That’s a model that’s worked for me. So, I don’t know if it can work for everybody, but for me, it’s working well.

VVG: So how long did it take before it was comparable to what you would have made otherwise?

HN: It took about 18 months. And actually, I had a friend who had a fairly successful Substack, Max Read, and he told me before I started, he’s like, ’18 months is where you should hit, hopefully, salary level, if it’s working.’ And it was almost exactly 18 months, really, when I got to what I felt like was a decent salary. So yeah, that’s what I would say, but you have to kind of have the discipline to do it for those 18 months and not give up.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Vianna O’Hara.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.