Guy Davenport on Ronald Johnson’s Transcendentalist Poetry

“The poet is at the edge of our consciousness of the world.”

“The green gold is the living quality which the alchemists saw not only in man but also in inorganic nature. It is an expression of the life spirit, the anima mundi or filius macrocosmi, the Anthropos who animates the whole cosmos. This spirit has poured himself into everything, even into inorganic matter; he is present in metal and stone.”

–Carl Jung: Memories, Dreams, Reflections

*

The philosopher Wittgenstein, from whose formidable talents came a house, a sewing machine, and an airplane propeller as well as the books for which he is honored, said toward the end of his anguished life that he had always wanted to write a poem but could never think of a poem to write. Nor did Heraclitus write a poem, doubtless for the same reason. Nor Leonardo, that we know of.

The miracle by which we have two poems from R. Buckminster Fuller, the Pythagoras de nos jours, rises from the transparent fact that Mr. Fuller’s Dymaxion prose has twice defied mortal comprehension and has twice been found to be readable when distributed on the page as poetry is, phrase by phrase, or “ventilated,” the texts in each instance being word for word the same. These austere extremes of the poetic imagination are useful if difficult evocations, for Ronald Johnson’s transmutation of the English poem reaches down to the very roots of poetry itself. If a poem has ever occurred to Mr. Johnson, he has never written it. At least he has never published it.

A poem as it is generally understood is a metrical composition either lyric, dramatic, or pensive made by a poet whose spiritual dominion flows through his words like the wind through leaves or the lark’s song through twilight. In the fourth part of “When Men Will Lie Down as Gracefully & as Ripe—,” Mr. Johnson performs for a passage of Emerson’s what Buckminster Fuller did for his own prose. He spaces it out and makes a poem of it, though this bald-faced act scarcely answers to the received notion of how a poem is written. It is not Wordsworth in his blue sunglasses pacing his gravel walk and dictating to Dorothy. Nor Jaufre Rudel tuning his lute among the nightingales at Sarlat.

It is not things which poets give us but the way in which they exist for us.

The lyric poem from Sappho to Voznesensky with all its variants and transmutations has become for us the model of all poems. The credentials of this ideal western poem tend to lurk not in the poem but in the personality of the poet. All that Byron wrote is somehow not as great as Byron. This illusion, fostered by the scandal-mongering of professors and the Grundyism of psychology, is a lazy and essentially indifferent view of poetry. The poet, who writes not for himself but to provide the world with an articulate tongue, longs to be as absent from his finished work as Homer. Objective and subjective are modes in the critic’s mind; the poet scarcely knows what they mean.

If the finely textured geometry of words Ronald Johnson builds on his pages is not what we ordinarily call a poem, it is indisputably poetry. It is poetry written to a difficult music (“a different music,” as the poet himself says). It is a poetry with a passion for exact, even scientific scrutiny. It incorporates in generous measure the words of other men. It does not breathe like most of the poetry we know. It is admirably unselfconscious—the work of a man far too occupied with realities to have given much thought to being a poet.

This objectivity is no doubt first of all a matter of temperament. It is no surprise to learn that the man himself writes cookbooks erudite enough to be published by university presses, seems to be something of a wanderer in a society where every man jack of us is bolted down and labelled, and that if he comes to visit he is apt to forget to go to bed and be up all night reading a book about the symmetry of the universe. It is perhaps unfair to give even so vague a glimpse as this of the poet, since he himself has shown us nothing more than his meticulous connoisseurship of the world as a system of harmonic advantages. “Nature,” says the very first voice of philosophy, “loves to hide.

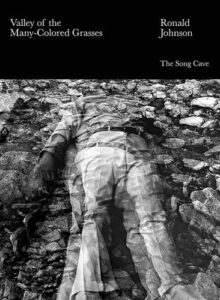

What is hidden in nature is more harmonious than what we can easily see.” The vision by which we discover the hidden in nature is sometimes called science, sometimes art. Mr. Johnson’s books—A Line of Poetry, a Row of Trees (1964), The Book of the Green Man (1967), and Valley of the Many-Colored Grasses (which incorporates a shortened and re-arranged version of the first book)—are about this vision in all its manifestations, from the scientific to the simple but difficult business of seeing the world with eyes cleansed of stupidity and indifference. Hence Mr. Johnson’s special fascination with men who have sharpened their eyesight: explorers, anatomists, botanists, painters, antiquarians, poets, microscopists, mathematicians, physicists.

Poetry from the old age of Browning to the old age of Ezra Pound has had a passion for objectivity. Whitman made a note to himself to invent “a perfectly transparent plate-glass style, artless, with no ornaments.” Mr. Johnson’s immediate patrimony in letters comes from Jonathan Williams, the poet, publisher, and a long-time friend. But Jonathan Williams is himself a kind of polytechnic institute, and at the time Ronald Johnson met him had already distilled from the confusing state of American poetry a clear sense that the masters were Pound, William Carlos Williams, and Louis Zukofsky, and had set about writing (and showing others, Ronald Johnson included, how to write) poems as spare, functional, and alive as a blade of grass. It was a poetry neither meditative nor hortatory but projective. It insisted that the world is interesting enough in itself to be reflected in a poem without rhetorical cosmetics, an arbitrary tune for melodramatic coloring, or stage directions from the literary kit and caboodle.

Art prepares its own possibilities for metaphysical shifts. We are at a point in the history of art when Robert Rauschenberg does not draw his drawings and is nonetheless a brilliant draughtsman. Charles Ives wrote his music and we must quickly add that of course he didn’t; these two statements exist in the realization that Ives is the most imaginative and accomplished of American composers. The quotations in Ronald Johnson’s poems are simply a part of the world, like Wordsworth’s daffodils, which the poet wishes to bring to us. The poet is at the edge of our consciousness of the world, finding beyond the suspected nothingness which we imagine limits our perception another acre or so of being worth our venturing upon.

It is always difficult to know how much of the world the artist has taught us to see; once we see it we are quick to suppose that it was always there. But there were no waterfalls before Turner and Wordsworth, no moonlight before Sappho. The apple has its history. For it is not things which poets give us but the way in which they exist for us. The rich theme of The Green Man has always “been there” in the history of things, in folklore, in architecture, in poems.

Some weeks after I read Mr. Johnson’s Book of the Green Man I was looking at Nelson Glueck’s book about the ancient Nabataeans and was able to say of the strange leafbearded and leaf-haired demons depicted there, “Here’s Ronald Johnson’s Green Man way back in the Biblical Edom.” Two days later the Jolly Green Giant suddenly lost his commercial enamel and stood there on his tin of beans as a household god thoroughly numinous.

“Every force,” said Mother Ann Lee of the Shakers, “evolves a form.” For the poet this is the opposite of supposing that a form can be filled with a force. The sentiments aroused by the moon painted by Ryder can be accommodated by a sonnet, but it is the sonnet in the end which is being accommodated, not the moon. In Ronald Johnson’s poetry form seems to have been compacted into diagrammatic elegance. What has happened is that the force of the subject matter has been allowed to shape the poem. “Eleanora,” the story of Edgar Allan Poe’s from which Mr. Johnson takes the title of this book, has for an epigraph a tag from Lully that is a corollary to Mother Ann Lee’s perception: Sub conservatione formae specificae salva anima.

The natural world is for Mr. Johnson the constant mode of nature; his every poem has been a search to find the intricate and subtle lines of force wherein man can discern the order of his relation to the natural world. These lines, as Heraclitus suspected, are largely invisible. About 2500 years ago poetry detached itself from the rituals of music and dance to go into the business of making the invisible visible to the imagination. This seeing where there is nothing to see, guided by mere words, is still the most astounding achievement of the human mind.

True imagination makes up nothing; it is a way of seeing the world. The imagination for Ronald Johnson is obviously a more complex process than we normally think it. There is the world to be seen, with its hidden harmony, and there is the poet (or painter, or composer) to perform the magic whereby we can possess the artist’s vision. There is more.

Throughout his poetry Mr. Johnson is interested to show us the world from multiple angles of vision, not only what he can show us but what others have seen also, so that we find ourselves not in the company of one poet but of many, and not only poets. All these voices quoted in Ronald Johnson’s poems are other modes of vision which he is allowing to play over the subject along with his own. In the later poems we have to learn to read two poems at once, as in “The Different Musics,” and to see with rapidly refocused vision, as in “The Unfoldings.”

True imagination makes up nothing; it is a way of seeing the world.

There is a wild freshness about these poems that cannot be accounted for entirely by their newness of form and greenness of imagery. In avoiding the traditional forms of the poem, including the super-traditional form of Modern Poetry, Mr. Johnson also escaped the emotional clichés that cling to them like ticks to a dog. Things wholly new are perhaps impossible and a bit frightening; like all things fresh and bright, Mr. Johnson’s newness is a re-seeing of things immemorially old.

In The Book of the Green Man he gives us a new look at Wordsworth, and adds Kilvert to the account; it is the conjunction, not the elements, that creates a new light. Much of Mr. Johnson’s imagery that seems so wonderfully clean and new has been discovered in out-of-the-way places. Invention, we remember, really means finding. The knowledge he likes to teach us is indeed knowledge all but lost. We scarcely think of the poet any longer as a teacher, but Mr. Johnson does; and if we like to think of the poet as our conscience and our political guide and a figure speaking of contemporary and fashionable anxieties, we discover that Mr. Johnson might just as well be writing in any century you might arbitrarily name for all the mention he makes of his times.

There is a brave innocence in this program, and an aptness that may not come readily to mind. It is characteristic of Mr. Johnson’s generation and its immediate predecessors that a mind of one’s own is preferable to tagging along with corporate thought. It was Louis Zukofsky, a friend of Whittaker Chambers and an alumnus of Columbia in its Reddest heyday, who read Gibbon with an eye to seeing what Marx would have done about it all and thus bade farewell to Marx and all his host. Stan Brakhage, the film-maker, once banned the newspaper from his house and substituted Tacitus, which he read to his family daily at breakfast.

He had reached the assassination of Caesar on November 22, 1963. R. Buckminster Fuller, a friend of Mr. Johnson’s, has noted that in nature there is no occasion on which the perimeter of a sphere is passed through its middle and has thus dismissed pi from his mathematics. One can note that we are here looking at an awful lot of Transcendentalism about which one could write quite an original book.

In a preface we can do no more than alert ourselves to Mr. Johnson’s Transcendentalism, note that he came by it honestly, and read him accordingly. Transcendentalism holds that a man must do his perceiving and his thinking for himself, and that he must learn how with much discipline and with constant awareness. Much that is new and rich in Ronald Johnson’s poetry can be traced to his having seen the contents of his poems with his own eyes, out of his own curiosity.

This charming doggedness, which Mr. Johnson shares with our best poets writing today, may have saved American poetry from another dismal return to the academic slush into which it is constantly threatening to sink. Sensitivity serves well for reading poems but not for writing them. The same Transcendentalism which flows from Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman into the best of our poetry is the tradition also whereby it is assumed by ninety-nine out of a hundred practicing poets that sensitivity is the whole apparatus for making a poem. Hélas.

The goodness of Ronald Johnson is in his having got the real Transcendentalism from the very start, the kind that served Ives and Buckminster Fuller, both of whom went back to the beginning of their arts as if time did not exist, and began anew. This is a tough and hazardous way of going about one’s art, especially if there are two thousand years of tradition at one’s back. And it requires enormous resourcefulness, sureness of hand, clarity of vision, and genius. But these Ronald Johnson has.

Read “The Garden” by Ronald Johnson.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Valley of the Many-Colored Grasses by Ronald Johnson, introduction by Guy Davenport. Copyright © 2023. Available from The Song Cave.

Guy Davenport

Guy Davenport (1927–2005) was a writer and painter born in Anderson, South Carolina. He attended Duke, Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar, and Harvard (PhD). He taught at Harvard, Haverford, and the University of Kentucky. His awards included the Morton Dawen Zabel Award for Fiction by the American Academy & Institute of Arts and Letters, and a MacArthur Fellowship.