Well, I had taken my Chinese ear-cleaning service to the West, because my mother had told me that tourists to the East liked to be fondled around the eardrum.

Back in the New Territories, she had started a healing business near Lai Chi Kok. She kept a leather case of various-sized ear scoops and rods and found a space where she would perform the ritual, welcoming both traditionalists and tourists. The manner of her business relied on creating an accessible space for both.

“The marketing,” she explained, “is the blueprint. The way you approach it varies according to the location, particularly in a city like Hong Kong.” If the studio was in, say, Central, the aesthetic would deviate from the way she would present it if it were located in an isolated little borough in Lai Chi Kok. Often she would send me email links to playlists she’s made to soundtrack the excavation of sebum from the ears of curious strangers and monthly regulars.

When I was a child, she would lay my head in the enclosure of her lap and shine a light into the hole on either side. Take me at the cheek with one hand, then take me by the ear. It was similar to a sort of tickling, only more euphoric. As if the feeling of constriction from being tickled

had been replaced with a feeling of gentle, spacious inquiry. The delirium felt its way between each hair as the scoop shrank its way in. Like the curved tip of a fingernail patiently chiseling a sculpture. Like a fly soaring around inside.

At age eleven I developed a brief obsession with this feeling. I would ask my mother every night to perform the ritual, anxious about the mud that might have clotted there, in the caverns, during the day.

Addictive. What you can’t see, you trust someone else to be able to somehow.

And so, I’ll be owning my own healing studio in the outer suburb of Par Mars, fitted into a storefront at the Topic Heights shopping complex. In with the lime and pale rouge diamond-shaped tiles of the food court, the off-white square tiles everywhere else. In with the big arches of skylight, the second-level balconies, rusted gold banisters like those in motels, the phone-repair stall in the center of the corridors. Every corridor organized by its genre of lifestyle, encouraging you to see and consider everything you might need.

*

The suburb has little sectors. The sun sets orange on the Home store, a bold stripe intruding upon its signage. The suburb sits just off a major highway, a McDonald’s planted at its entrance. There are never any children in the PlayPlace there. This McDonald’s establishment only seems to appeal to the morning commuters, the truck drivers. The streets behind the Home store and the McDonald’s are where the residential neighborhoods begin to germinate, a healthy mixture of young families and parents with older children, an area with a fairly even ratio of recent immigrants and long-time settlers. The wealthier have migrated out here for the estates, pools of carefully thought-out architecture, often following a thematic scheme design. Surrounding the estates are leftover swaths of suburb. The only way to tell the status of a household is by the state of its garden and how awkwardly it is distinguished from the rest of the street.

If you drive down this highway at the coil before sunset, the reflection of the sunlight on the road bounces up to pierce your eyes, preventing you from seeing the cluster of traffic lights ahead.

Traffic is allowed between forty and sixty miles per hour, varying according to how many concrete warehouses are established on either side. The scatter of palm trees every so often keeps the grayness subsided, keeps the grid-like formations from looking too much like an abandoned military site.

If you have the windows down you can smell summer even if it happens to be winter.

And as you make a right turn down Brandt Boulevard, the sun peeling itself through the trees in the front yard of somebody’s home.

The first house on the corner still has its Christmas lights up, you’ll notice. Red ones, which match the sign reading NO PARKING AT ANY TIME. Regardless, a few feet up, someone has hoisted a Volkswagen up onto the curb the way cops do.

Gradually down Brandt Boulevard the street begins to widen and an extra lane of gravel forms. Here at the corner there is a swift turn and a group of units on the left. They are not currently inhabited, and even after three years, the local council has still not decided what to do with them. The unoccupied units have been such a regular topic of community discourse that asking about them has become a pleasantry, as mundane as asking about the weather.

One house has a purple tree in front. Next to it starts to form another industrial area: empty parking lots, wire fences; you can see folds of mountains from this parking lot. One of the Office Mart storage sites is here. A youth group I’d attended rents one of these on Friday nights.

Drive further and you will come to an intersection with a coin laundry and a liquor shop.

Past this intersection the roads open up into lakes lined with short white metal pole fencing as if to imitate white picket.

The left side is certainly prettier than the right.

We live on the left side. A flat, open lawn between two concrete houses. Steep driveways on either side that lead to four more condominiums in the back. Overgrown garden and children’s toys. Three tall palm trees, some succulents, and orange roses. In the back, a pool sits in resin-bound gravel, fenced off with aluminum.

Dominique owns the second-to-last condominium in this arrangement of units. Where she lets Vic and me live too.

If you were to keep driving from our house and head east for another ten minutes or so, you’d arrive at some of the estates. These are the real treasures of Par Mars. Where the roads narrow into quaint rivers. Within these lush networks of houses, each property is larger, with more effort put into the transplantation, the foliage; imported, rare flowers. There is the Beverley Estate, where palms fan over the peculiar, box-shaped models wearing timber awnings. It takes after the organic beauty of a kind of woodland; a labyrinth highlighting the precious fabrics of a forest. A few minutes’ drive over, you arrive at the most recently erected community—two hundred southwestern-style homes, appropriated from the style of Native American villages during the sixteenth century. This is another common discussion between locals: which aesthetic will be adopted for the next land package investment.

The Topic Heights shopping complex is at the heart of all these clusters, a perfect centrum, the exact summation of every need and personality of the people residing in its hem. It’s where we get our clothes, where we find things to eat, where we determine what the inside of our houses will look like.

The Topic Heights shopping complex sits on the same highway as the Galleria shopping complex, ten minutes down. Only, the Galleria, with its domed white body and spiraling roundabout roads that spill into the different parking lot sections, is spectacular to look at.

Hilly roads lead off to State Route 96, directing you out to other zip codes and, if you wish, eventually to the coast.

When I get inside, Doms is sucking a splinter out of her hand.

She’d been making soaps when I left for my final shift at the public school a few hours ago. She plays the Leslie Cheung I showed her last week, lets incense run through. Doms has a habit of stopping halfway through the soap-making process to walk around our condo village. She stares at the flowers by the fencing of the pool and checks the fruit and marijuana trees she and Vic planted two summers ago.

“Vic still at work?” I ask.

“I think so.” Doms blinks at me, then looks at the television, which is playing a K-drama. Her cheeks have a hot boredom about them; she tells me to come sit beside her. Our couch is situated against the window, where she is able to tan easily; often she will be there, her legs stretched out. Peeling fruit or organizing dried flowers, barely looking at what she’s doing. Her white skin, drowning in evening sun.

The drama is in Korean, which she understands a little of and is learning as a way to connect to her maternal grandmother, who she otherwise knows very little about. She doesn’t usually keep the English subtitles on because she is looking to improve her speaking of it as quickly as possible. She can be selfish like that, and often dreamily involved with the idea of domestic possessorship. She enjoys making the point very clear that these are her floorboards, her walls that we rotate within.

I stare outside, which is looking nice. A warm breeze blows and the palm trees gesture. A Lord Jagannath smile sticker is stuck on the window. It blocks the sun from piercing the side of my eyes if I’m sitting on the couch in this position, watching television at exactly this time.

“So where’d you go?” Doms stands up from the couch, pausing the television from her connected laptop.

I tell her I finished my last day at the after-school program. Doms raises her eyebrows.

*

It’s felt like the same day repeating itself for some time now. I come home around five, Vic gets home around seven. The excitement of our workdays ending merges with Doms’ restlessness, finding us in the same position by nine.

Our internal chemical environments mirror our external natural environment. Lethargy reflected in the dry leaves sitting atop my fold-out bed in the corner of the living room, the laptop still attached to the television with a taut cable, the once-novelty, boxed almond milk on the bench.

The rhythm of our schedule of emotions is dictated by the free and almost stylistic disorganization of this condo.

Our bodies may appear to be yeet hay, a term my mother uses to describe the disruption in one’s equilibrium caused by hotness, the acidic boiling of blood or hot air present in the body from subtle stressors that cause subconscious anxiety. Depending on the body, these stressors can be spawned from different elements: processed sugar in sauces, the energy of excessive peanuts, the constancy of television, not the smoking of cannabis itself but perhaps the lingering of its cold resin.

This rhythm of living felt exciting and uncontrived at first, like how it feels to be raw. It was our attempt to draw closer to our own skin. But it’s been a year now since Doms won the lottery on the cusp of finishing her degree in chemistry and we keep falling into this rhythm. We make up our days as we go, letting our habitat speak for our moods and anxieties. We suppose this must be happiness.

Sometimes Doms and I will walk around the poolside, circling a few times before jumping in. Feet are more sensitive to temperature variations because they’re at the ends of us: thresholds for our bodies’ heating and cooling. We let our soles start to burn, then jump in, the adrenaline bloating us, the impact collapsing us. It’s exciting every time.

*

This evening, Doms and I are sitting in the living room watching a TV Western when we sense that Vic is back from work. Broad headlights are riding across the ceiling, then back down the wall again, scouring. A car door slams out front. The place smells like cinnamon and hemp.

“You’re not eating that, are you?” Doms points to the cheesecake on a napkin.

I shake my head and she takes it.

We hear a cough, then a knock, keys jangling, then watch as Vic comes reluctantly through the door. A slight barbecue wind wisps through the air along with him. As his body becomes visible in the light from the television, we notice blood on his white pharmacy coat, dried up and molasses-like in his facial hair.

“They saw me,” he says quietly. “I just was walking home and they cornered me.”

“Who?” Doms stands to hold him, hanging her arms around his neck, patting his body as if to feel that it’s there. She hurries to the kitchen and runs the tap.

“No, I’m fine, it’s just—” Vic looks down at his combat boots, still on. Licks his bottom lip. Shakes his head and exhales.

Doms returns and wipes him.

At the dinner table, sitting a few feet from the couch. We’ve just finished a joint, now taking turns to rip a baguette, dipping the bits into leftover jarred chipotle mixed with Greek yogurt, conserving the flavor of the more expensive product.

Then, without considering the rhythm of the moment, Vic says, “I thought I was going to die, but everything seems ridiculous now.”

After I’ve showered, I find it’s half past two in the morning. I come out and see Vic and Doms wrapped in each other’s arms, talking softly, smoking cigarettes on the couch. Doms has her arm around Vic’s head, her fingers playing through his hair. His face has been cleaned up. My fold-out bed is beside the couch. Doms offers me a cigarette when she sees me in the archway. I shake my head and go stand in the kitchen.

*

I follow the news like it’s a series. It’s the way they run network television in the suburbs, the way it plays nicely, as if for its citizens. As if everything was always meant to happen.

Back in the Territories, they program the television as if it’s a time machine. My mother watches a kung fu period soap in a frosted-blueglass apartment, seated at the dining table drying clear plastic cups. Laundry hanging out a small window and the city lights hovering across the harbor.

For a few days, we turn the television up while eating prepackaged dinners. In recent news, they’ve been trying to catch a brunette dadlooking man who is described as a local basketball team manager, a retired cop, and now a member of his local neighborhood watch council. According to the first presenter, his behavior has been self-serving, strangely cultlike, and “religiously” driven. The other presenter remarks, Doesn’t sound very religious to me. They show surveillance footage of him walking around the shopping complexes, wearing a father’s camping-gear fleece and New Balances. He’s the antihero inside every suburban house.

Vic is sitting on the floor between Doms’s legs, painting his fingernails with the white polish he took from the pharmacy.

“That was the guy,” he says softly.

Doms says, “Which?”

“That was him, the guy who attacked me.”

Doms stares miserably. She doesn’t seem to know what to say and Vic is avoiding eye contact.

“Religious?” says Doms.

Vic flashes his eyes at me briefly, his tongue seated on the inside of his cheek, nodding from side to side. Doms is shaking her head, watching intently on the edge of the couch.

The program shows the man browsing through clothes in the Target. Once or twice I think I catch him skimming his translucent eyes over the camera’s lens.

*

On Thursday night’s program they finally decide to catch the man and wrap up the segment. Some of his close accomplices from the ex-cop club too. He and the line of police that march him out are looking straight into the pupil of the camera. There is hot rain tonight. We change to the TVB Korea Channel and arrive on a game show. Doms seems to understand a lot of it and is laughing loudly. Vic gets up to continue scrubbing at his pharmacy coat, blood still stained in the collar.

I return to the video I’d been watching earlier in the afternoon: an analysis of the first scene in Blue Velvet when a lovely man suffers a heart attack on the front lawn.

It seems as if the violence will be over for a little while.

__________________________________

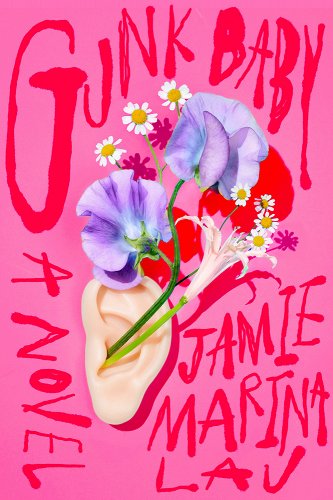

Excerpted from Gunk Baby by Jamie Marina Lau. Published by Astra House. Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved.