As days passed, the signatures above the shop entrances and display windows began to form an accompanying text to the colors of cliffs and stone, tiles and roofs, to the grain and texture of things, which shifted with the light and weather. They suited the sounds of the words, with their slurred sibilants and broken-off syllables. There were three cobblers in the village. Two often stared idly over the chest-high partition-wall of their window display featuring shoe creams, brushes, shoetrees, and some old cobblers’ tools. The third worked behind a high shop counter, from a barstool. Customers and acquaintances never failed to appear before him. At times it became lively—the sound carried into the lane. High on the rear wall, practically at the ceiling, hung an old poster on which I thought I recognized, in addition to a warplane with the colors of Italy, the outline of Mussolini.

Every day I encountered the same faces, winter coats, and hats. I became acquainted with several rules of etiquette, such as not to touch the goods before purchasing them, how to politely order from the vegetable woman, and to always follow the recommendations of the cheesemonger, whose ever-smiling, chubby daughter sat on a stool at the register, making a great effort to add small sums. Only at the Arab vegetable shop, which had no name, was one allowed to touch the fruits and vegetables, to pick them up and put them back down again. This liberty must have led to the mass of spoilage behind lock and latch, which was visible only from my veranda.

Coming back from the village I passed by a bar, where even on the coldest days people sat out front on a bench. If the winter sun was shining this bench was especially well-placed, lying for several hours in the light, and so it was a popular meeting point. The people on the bench smoked and talked, some with drinks from the bar, the interior of which was barely visible behind fogged windowpanes. Perched between the smoking men was often a nervous girl, who had a baby carriage with her. If the baby cried she would jiggle the carriage forcefully, while passersby stopped and bent over the crying baby, and the smoking men on the bench laid their hands soothingly onto the blanket and mumbled pleasantly, cigarettes fuming between their fingers. If the baby did not settle down, the girl would stand up and rock the carriage back and forth in front of the bench, all the while talking in a hoarse voice and laughing loudly. She had short hair and dressed like a boy, in a beat-up leather jacket and heavy army boots. She begged the men on the bench for cigarettes. They were generous and complied, and she lit them hastily. Her hands were nearly blue from the cold and chapped, with gnawed nails.

Located across from the bench was a butcher. Meat was delivered in the mornings—almost every day I saw a delivery van parked there, with half-carcasses hanging inside. The delivery man shouldered a pig carcass and moved gingerly, stooped as if carrying a delicate, needy creature. The rear pig’s trotter dangled limp, yellow and rindy on the man’s back. After the pig, he carried a bundle of chickens into the shop hanging headfirst, and occasionally additional cuts of meat, as well. Once he was done with the delivery, in his stained smock he joined the smokers on the bench and lit a cigarette, though always at a certain distance. He bantered with the hoarse girl and seemed to be altogether witty—in his presence there was laughter. All the while the rear door of his delivery van remained open, and anyone could peek at the butchered goods inside. Back at the butcher’s, the delivered parts disappeared into the rear of the shop where, through a small window, positioned behind the meat counter, you could watch the sausage maker at work. The sausages from this butcher were famous and highly sought after, and day after day a vast amount of meat was pumped out of the grinder into long skeins of casing, which at fixed intervals an assistant fastened a few times with twine before twisting. Later these fastened bulges would be sealed with metal rings at the base of the sausage. The long sausage chains were then hung and looped several times around rods, just beneath the ceiling.

On the windows positioned barely above ground next to the butcher’s shop was written, in elegant letters: Onoranze funebri Pizzuti. A few steps led down to a door, which I never saw open. Nor did I ever observe light in these windows; it must have been dark down below, even by day. I imagined that these half-subterranean rooms were also damp and freezing now in winter. But the Pizzuti undertaking business was represented not only in these vaults; it was omnipresent in the village, and the finely lettered windows might have merely advertised the

place where the coffins were stored, conveniently located directly across from San Rocco, the church nearest to the cemetery, whose bells were always first to strike the hours and quarter-hours. There was a Pizzuti wreath and flower shop farther below in the village, where women were invariably occupied with putting together large, colorful floral arrangements, and farther was a large storefront office with catalogues in the display window featuring coffins and grave decorations. There the bereaved were advised on next steps. A glossy gray-black hearse, which had the same inscription as the windows next to the butcher’s, often edged broadly through the narrow village lanes, usually empty, and it always caused a bit of commotion when rounding the particularly sharp and tight curve in front of the Arab greengrocer. Occasionally I saw the hearse, filled with flowers and wreaths, parked next to the church when a burial lay ahead. Funeral services were all held in San Rocco—or at least I never observed the Pizzuti hearse at any other church.

The driver, in livery and a large hat, stood like a watchman beside the vehicle as singing came from the building. On such occasions the square was usually full of men. Women went into the church; I once saw the crowd part for two women in black, forming an honor guard, and as soon as they had disappeared behind the church’s doors the men reconvened into the same group they had formed beforehand, smoking and talking gravely. The Pizzuti driver, who also smoked, always had company, but in contrast to those around him there was something about his posture that was almost soldierly, due perhaps to his heavy peaked cap with a golden P.

I avoided looking at the coffin, which after the service was brought out to the hearse and slid into a sea of flowers. Sometimes after arriving back at my apartment I would lookout the window down to the street, where an unfailingly small funeral procession trickled to the cemetery. The guests had surely already expressed their sympathy at the square, and for many this journey would have been too arduous. I was never witness to a ceremony, never saw a coffin being lowered into a grave or slid into a fornetto. I only came across the accumulated bouquets and flowers, which wilted away and ultimately ended up on one of the trash heaps, evidently later dispersed among small fire pits and burned. Animals also tampered with the trash, and, on stormy days in particular, dogs appeared, having found their way in between the bars of the gate, and descended on the artificial flowers, shredding them and trailing torn petals out into the street.

__________________________________

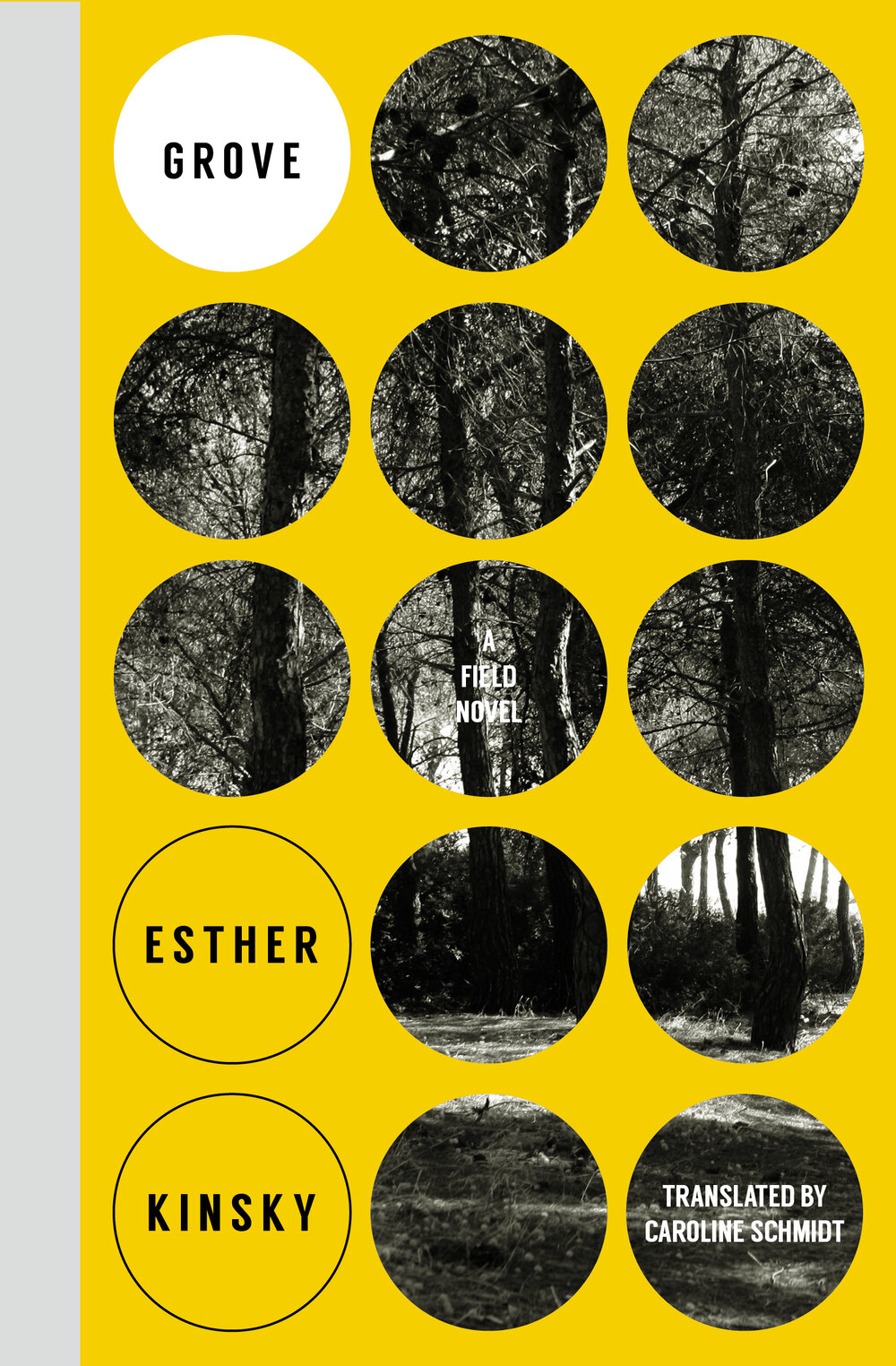

Excerpted from Grove: A Field Novel by Esther Kinsky and translated by Caroline Schmidt. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Transit Books.