Gregory Pardlo on Form, His Father, and Not Writing a Book About Race

The Pulitzer Prize-Winning Poet Talks his New Memoir in Essays, Air Traffic

When Gregory Pardlo won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for poetry for his collection Digest, which the judges lauded for its “clear-voiced poems that bring readers the news from 21st-century America, rich with thought, ideas and histories public and private,” he was still an MFA student—in nonfiction, at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. Pardlo had previously completed an MFA in poetry at New York University, where he was a New York Times fellow; his first book of poetry, Totem, had won the American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize in 2007; he’d taught poetry at George Washington University and Medgar Evers College and was an associate editor at Callaloo; and he was also working on a PhD at the CUNY Graduate Center.

Pardlo had sought out the nonfiction MFA program at Columbia not for another degree—he told me that to him, it was a “piece of paper” that comes along with the work—but for the opportunity to work on a book about his father’s legacy of manhood and his own struggle to escape it. That book would become Air Traffic: A Memoir of Ambition and Manhood in America, out this week from Knopf.

Pardlo’s father, Big Greg, was a man of immense ego, machismo, and charm, an air traffic controller who was, as Pardlo writes, “mechanized, an arrow in the quiver, a rod in the fasces, proscribed to a bureaucratic engagement with data” in the tower while speaking in language that was “dismissive, hostile, and unpredictable; almost baffling“ at home. Air Traffic meditates on Pardlo’s father’s legacy, and the ways in which Pardlo struggled to differentiate himself from both his father and from preconceived notions of masculinity and race. At the heart of the book is Big Greg’s participation in the air traffic controllers’ strike of 1981, which cost him his job and destabilized the family’s rise through middle class stepping stones in Willingboro, New Jersey—a Levittown, and thus the epitome of the suburbs.

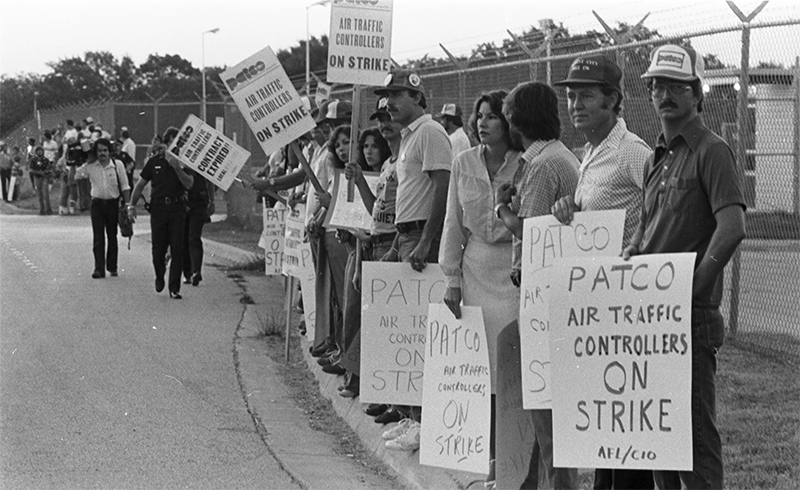

Picketers at the 1981 Air Traffic Controllers Strike. Photo via the Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Library.

Picketers at the 1981 Air Traffic Controllers Strike. Photo via the Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Library.

Though Air Traffic moves more or less chronologically through time, it is not a straightforward memoir—Pardlo considers it a memoir in essays. The pieces that make up the whole refract from the center to circle around and question the influence of class ambitions, inherited alcoholism (Pardlo’s brother Robbie, formerly of the hip-hop group City High, was featured on an episode of Intervention), and racial stereotypes on Pardlo’s life.

It was at Columbia, where we were classmates, that Pardlo began leaning towards essay writing. We met in January at his brownstone in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, to talk about how Air Traffic developed over the course of his time in the MFA and beyond.

Sitting in his living room, with his older daughter’s harp in the corner, a wall lined with bookshelves to his back, and jazz on the radio, Pardlo told me that he originally conceived of the project as “a book about the strike . . . a labor history.” In the title essay of the book, which delves into the strike, Pardlo opens by describing walking the picket line as a 12-year-old with his father, who yells at hecklers.

. . . when he throws up his hands and cries, “What, and leave show business?” he brandishes his placard like a spear. “Figure it out,” he tells me when he mistakes the look on my face for confusion. Of everyone here, I’m the one who has the least trouble deciphering his private meanings. As the world’s leading scholar on Gregory Pardlo, Sr., I know these pronouncements he’s polished, these homemade koans impenetrable to reason, that were once the punch lines of tired jokes. The jokes themselves are vestigial. He no longer needs them, confident his enemies will notice the deft lacerations of his wit in some later moment of quiet reflection.

By the time he entered Columbia, though, Pardlo’s thoughts on the project had shifted: it would be “straight memoir,” a “kind of coming-of-age novel” in nonfiction. He arrived to the MFA with about 300 pages of that memoir written, but after studying with the essayist Phillip Lopate, “everything went out the window.” Pardlo said that he saw “all of the possibilities for a poetic sensibility in the essay.” He found the analytical capacities of the essay appealing: “It allowed me to flex my academic muscles and scholarly muscles, as well as, clearly, the poetic muscles . . . Constructing a plot, that idea of linearity just felt like work to me. That the essay didn’t demand that from me was attractive.”

After working with his agent Rob McQuilken and editor Maria Goldverg, Pardlo said he “started to see the patterns from across the essays, and then [I was] writing towards those patterns . . . highlighting more and more the consistent threads.”

One of these threads deals with Pardlo’s father and his elaborate use of language—and how that became an arena in which Pardlo sought his father’s approval. In an early piece, “Student Union,” Pardlo writes of the start of his father’s career as an extemporaneous speaker, as president of the Black Student Union of Germantown High School. In 1960s Philadelphia, speaking at a school board meeting, Big Greg said: “‘What we have here is a failure to communicate . . . It only takes a cursory perusal to ascertain the disregard this august body has for the well-being of black youth.” Pardlo writes that his father’s speech was “further laced with lines he’d memorized from the St. Crispin’s Day Speech of Henry V, and from the Rudyard Kipling poem ‘If.’ The point here was not merely to persuade, but to dazzle.”

That ability to dazzle was something that had always stunned Pardlo. He told me, “I mean, the reason, not the reason, but one of the major reasons why I’m a poet, which I don’t often talk about, is that I could never speak as extemporaneously and eloquently on the spot, as persuasively as my father could. The only place where I could even approximate that was on the page, because I could come back to it and rethink it.”

Big Greg, though, saw no reward in writing, and while he liked the Kipling poem when spoken, he said he didn’t “get” poetry—Pardlo writes, “Poetry, my dad said, is like a game at a children’s birthday party. What’s the point if everybody wins?” Even at the party Pardlo’s mother threw to celebrate his winning the Pulitzer, which he recounts in Air Traffic’s introduction, his achievement—his winning—had merely created a performance opportunity for Big Greg: “I was the opening act. My father loved me, and was indeed proud of me in his complicated way, but he came for the crowd.”

“I could never speak as extemporaneously and eloquently on the spot, as persuasively as my father could.”

That party was the last time Pardlo saw his father, who died in May 2016, while Pardlo was finishing Air Traffic. Of his father’s death, Pardlo writes, “By some concoction of sugar, nicotine, prescription painkillers, rancor, and cocaine, my father. . . began killing himself after my parents separated in 2007. . . He lived his last years like a child with a handful of tokens at an arcade near closing time.” While writing the book, Pardlo interviewed his father extensively, aware each time that it might be their last conversation. “There was always this kind of over-the-shoulder, ‘take care of the farm,’ [comment],” he said, and laughed.

When I asked Pardlo how he thinks his father felt about Air Traffic, he told me a story about his father’s reaction when he sold the project. “I texted him, I said, ‘did you hear that I sold the book?’ And the only thing he wrote back was ‘Denzel Washington’”—the actor he wanted to be played by in the movie version of the book. “This is classic Big Greg!” Pardlo said. “He goes straight to the end game.” For his father, Pardlo said, life was “spectacle—everything’s a game, a performance.”

Big Greg’s penchant for performing meant that he hated to be seen “trying or developing,” Pardlo said. As he writes in “Student Union,” his father had a “refusal to make himself vulnerable to authority figures.” That ego and machismo complicated their relationship.

Pardlo explores the history of machismo and questions how to be an ethical, sexual person in one of the most fragmented, poetic chapters of the book, “Hurray for Schoelcher!”. The piece takes its title from an anecdote in Franz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks: “‘a coal-black Negro, in a Paris bed with a ‘maddening’ blonde, shouted at the moment of orgasm, ‘Hurrah for Schoelcher!’’ It was Victor Schoelcher, Fanon reminds us, who pressured the French Third Republic to abolish slavery.” The piece, which incorporates “vagal tone”—which Pardlo defines as “the ability to make and hold eye contact, as well as having the ear for subtle fluctuations in attitude”—racial stereotypes, and the Talented Tenth, sifts in aspects of Pardlo’s doctoral research.

While at the Graduate Center, researching what constitutes African-American poetics, Pardlo became interested in visual practices. “If race is constructed primarily visually, and I’m thinking about these prohibitions on black sight: blacks were not allowed to serve as witnesses in any court, they were not allowed to even witness themselves . . . there was a prohibition on looking a white person in the eyes,” Pardlo explained. “I’m thinking about [the philosopher] Emmanuel Levinas, who says the foundation of ethics is in eye-to-eye contact. So then I’m thinking, well, what constitutes an ethical poetics if the eye-to-eye contact is at least traumatized, if not prohibited all together?” These are all live questions in “Hurrah for Schoelcher!”

In that same chapter, Pardlo writes that, “If I was raised black for the most part, it was for economic reasons and apathy. Growing up, my family was not observant, preferring instead to derive our esprit de corps from the community of consumers we’d gather in fellowship with in the tabernacle of Macy’s, the mead hall of IKEA. I am not, in other words, a practicing black.” This line, Pardlo said, gave him “a kind of agita”—he felt a nagging tension about it. “Whenever I feel myself getting antsy or nervous about a particular passage or something that I’m writing, I feel like, ‘Well, it’s absolutely necessary that I write that now,’ ” he said. In this case, the line gave him an “anxiety that I’m playing into this narrative of self-loathing, and that it is a rejection of black people. It is not. It’s a rejection of race, not only as a construct, but as a narrative . . . I felt that at some point in the book I had to do some violence directed toward the story of race, toward the idea of race. And if I didn’t expressly reject race, then it would too easily—all the narratives, the stereotypes would settle like dust on the book.”

It was thus by design that Pardlo left race out of the title of this book. “I absolutely refused to write a book about race,” he said. “I stepped back and started to appraise that tension: why am I so at odds with discussing race? And that became the sort of focal point for me. Not talking about race, but talking about the ways in which I’m at odds with that structure, how I selectively fit into and reject that structure.”

“If I didn’t expressly reject race, then it would too easily—all the narratives, the stereotypes would settle like dust on the book.”

Another structure under Pardlo’s microscope in Air Traffic is that of class, and how his upbringing in Willingboro shaped his sense of ambition. One of the chapters, “Cartography,” traces Willingboro’s history as a Levittown and the invisible borders between its subdivisions. Pardlo said he was interested in that history and in how his hometown has declined from the “ambitious, upwardly mobile, vastly class-stratified” place it once was.

“Growing up, I didn’t know, in my naïveté, that this was a kind of contained Monopoly board of middle-class America,” Pardlo said. “I saw class mobility as these stair steps, and my family moved from Fairmount, to Twin Hills, and the next step would be to Country Club Park . . . which was thrown up and disrupted by the strike, and my family’s, as I call it, flatlining. Which is not entirely true, because my mother got this executive position, and we were for all intents back in business with her success there. But then she hit the glass ceiling.”

Interrogating the story of his family’s “flatlining,” as well as the story Pardlo tells himself about his having “ran screaming out of Willingboro,” has caused him to meditate on his own ambitions and desires. Talking about settling down in brownstone Brooklyn, Pardlo said, “In one of the archaeological levels of Bed Stuy is Willingboro. One of the questions I’m asking myself is about how what I want manifests in various ways, how I may not say outright, I want two kids, a fucking bunny rabbit, a Volvo station wagon, you know.” But that’s what he has—Oliver is the family rabbit, who refused my affections in favor of hiding behind a butcher block in the kitchen.

At heart, Pardlo still sees himself as “a materialistic kid from Willingboro. So all of my idealistic, artistic values are very much intact, but my ambition is still informed by my father’s value system.” When I asked him if he felt like he has achieved what he wanted from his literary career now, he said no, and we burst into laughter. “It’s insane,” he acknowledged. “But—and this is a conversation I had with my therapist—it’s not possible. Because what I want is an impossibility, and I’m healthy enough to understand now that I am motivated by the desire for something that I can never have—something that can never exist. Because, the fantasy of New York literary success—my life, no life looks like that. You’ve gotta put the trash out. The toilet’s going to break. There are drafts in the fucking windows!”

Though Pardlo is still not completely satisfied, it’s that lack of complacency that pushes him to keep working—and that gave us Air Traffic, a restless, probing memoir.

Kristen Martin

Kristen Martin is working on a collection of essays that meditates on grief, death, and life. Her personal and critical essays have been published in The Cut, Hazlitt, Catapult, Real Life, and elsewhere. She received an MFA in nonfiction writing from Columbia University, consults with writers at the Columbia University Writing Center and teaches writing at NYU.