Gray Area for Gray Matter: On the Time Einstein’s Brain was Stolen

A Quest for the Biological Basis of Genius

“Einstein was a world-famous genius and people I knew used to remark, ‘You spend a good deal of time with Einstein. He has a perfect brain, doesn’t he?’”

–Physicist Eugene Wigner

*

When Albert Einstein was alive, even people who didn’t think his brain was exactly perfect suspected it was different, better in some way than your average didn’t-come-up-with-relativity-and-never-could kind of brain. But different how? No one knew. After all, it’s a tad difficult to analyze a brain in its original container. Then, on April 18, 1955, at age 76, Einstein died—and an intrepid pathologist seized the opportunity to seize the brain.

Einstein had been in the Princeton Hospital suffering from intense abdominal pain; on the table beside his hospital bed were scribbled notes, thoughts on how to make the theory of relativity jibe with quantum mechanics, part of his work on the so-called theory of everything. But at 1:15 a.m., his body—and his still-active brain—finally stopped. According to the nurse on duty, Einstein took several deep breaths, muttered a few words in German, and died.

Princeton hastily called a press conference announcing that the genius was dead, while the body was whisked to the lab for an autopsy. Pathologist Thomas Harvey performed his straightforward task to officially determine the cause of death. (As suspected, a long-standing aortic aneurysm had ruptured.) But then, instead of sending the body back to the family for cremation as planned, he added an extra step: He removed Einstein’s brain. (In the spirit of collegial sharing, he also removed Einstein’s eyes for Einstein’s ophthalmologist.) Only then was the body sent back to the family, who had it immediately cremated later that day and the ashes scattered without any publicity per Einstein’s wishes.

The family had no idea that they had received only a partial Einstein until the next day when they got their New York Times. There, in a front page article with the compelling headline “Key Sought in Einstein Brain,” they read that “the brain that worked out the theory of relativity” had been removed “for scientific study.” Confused, Einstein’s son Hans Albert and his executor Dr. Otto Nathan went to confront the improvising pathologist who admitted that, when faced with this unique chance to harvest the brain of such a genius, he took matters—and the brain—into his own hands.

But then, instead of sending the body back to the family for cremation as planned, he added an extra step: He removed Einstein’s brain.

Harvey was following in the footsteps of scientists (and “scientists,” for that matter) before him who were gripped by a sort of, well, brain fever—the pressing urge to study brains firsthand, particularly those of the famous or, in some cases, infamous. This zeal for gray matter began millennia ago in the 5th century BCE when Alcmaeon of Croton came up with the idea that the brain was the seat of our consciousness. From that point on, brains were a focal point of research, and dissection of brains became a crucial method of study. But fads come and go, and for a while cutting up human bodies in the name of science (versus acceptable dismembering in the name of war and nationalism, of course) was frowned upon. It wasn’t until the 13th century that scientific human dissection began in earnest again, and it wasn’t until 300 years after that, that brain research made a huge leap with the development of soft tissue preservation methods that allowed researchers to collect organs for study.

Brain collections really hit their stride in the 1800s. All things brain-related were hot—from phrenology, the “scientific” study of bumps on the head, to atavistic classification, linking head shape and size to criminal tendencies, to, well, just brains. The study of brains was in high gear. Scientists collected them, analyzed them, and compared them.

In the late 1800s, one researcher, Burt Green Wilder, divided his brain collection into two main sections: “Brains of Educated and Orderly Persons,” that is, those belonging to (white male only) scholars and notable luminaries, and “Brains of Unknown, Insane, or Criminal Persons,” which included not only the mentally ill and criminals, but also minorities and women. Brain societies or “clubs” formed—scientists and interested laypeople banded together to discuss brains, to promise their own brains (post-death, of course) to the club for eventual study, and to convince the famous to similarly bequeath their brains. At the bottom of all this brain fascination was the belief that surely there was some difference in the brains of the best and the brightest, something that distinguished them from other brains… which brings us back to Harvey and Einstein’s brain.

The family owed the brain to science, Harvey argued. Although no agreement was formally put into writing (one of the reasons Harvey was long dogged by stories about how he “stole” the brain), the family and the executor ultimately accepted Harvey’s action and agreed that the brain could be studied. But there was one major stipulation: In keeping with Einstein’s desire to keep as low a profile as possible, the family wanted the whole process kept quiet; no public relations blitzes.

At the bottom of all this brain fascination was the belief that surely there was some difference in the brains of the best and the brightest.

They got their wish. Nothing Einstein-brain-related appeared in the media; no studies were published. The brain dropped out of sight and mind until 25 years later, when an intrepid reporter for New Jersey Monthly magazine went on a “find Einstein’s brain” quest. Reporter Steven Levy ultimately tracked Harvey down in Wichita, Kansas. There, Harvey showed Levy two jars in a cardboard cider carton filled with crumpled newspaper tucked behind a beer cooler: “Floating inside [a mason] jar … were several pieces of matter. A conch shell-shaped sized chunk of grayish, lined substance, the apparent consistency of sponge …”

And in a second larger jar, with its top held on by masking tape, were “dozens of rectangular translucent blocks, the size of Goldenberg’s Peanut Chews, each with a little sticker reading CEREBRAL CORTEX . . . Encased in every block was a shriveled blob of gray matter.”

Meet Einstein’s brain.

Harvey explained that he had cut the brain into 240 samples and had made microscopic slides that he sent to prominent neuropathologists. While he had kept the rest of the brain for his own research (which he never did), Harvey had hoped and expected that other more prominent scientists would be eager to study Einstein’s brain. But many weren’t very interested, not in the least because there was some controversy about the ethics of the whole brain-removal incident. It wasn’t until decades later that studies were finally published.

So did studying Einstein’s brain shed light on the genesis of genius? It’s difficult to be certain, but researchers think they’ve made some notable findings. A 1999 study done by researchers at McMaster University found that Einstein’s brain was actually smaller than average, but certain parts of his brain, like his parietal lobes, were larger than average and more highly developed.

More than a decade later researchers at the University of California at Berkeley found that he also had a higher ratio of glial cells to neurons and a higher number of connections between all those glial cells. (In layperson’s terms, this means that Einstein may have had enhanced cognitive ability, that he could make creative leaps more easily than most.) But this was—and is—conjecture. We’re still only beginning to understand how brain structure contributes to intelligence.

Harvey never knew his “theft” of the brain was to some degree vindicated. He died at age 84, years before the more interesting studies had been issued, breathing his last in the hospital where Einstein had died and where he had initially taken the brain.

______________________________

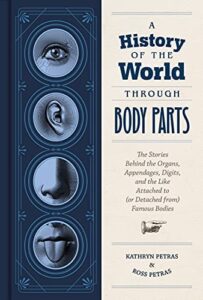

Excerpt from A History of the World Through Body Parts: The Stories Behind the Organs, Appendages, Digits, and the Like Attached to (or Detached from) Famous Bodies by Kathy and Ross Petras, available from Chronicle Books

Kathryn and Ross Petras

Kathryn and Ross Petras are a sister-and-brother writing team and authors of many word-oriented books like the New York Times bestseller You're Saying It Wrong, THAT DOESN'T MEAN WHAT YOU THINK IT MEANS, as well as Very Bad Poetry and Wretched Writing. They've also compiled a series of bestselling quote books like Age Doesn't Matter Unless You're a Cheese and It Always Seems Impossible Until It's Done, as well as the page-a-day calendar The 365 Stupidest Things Ever Said (now in its 24th year – with over 4.8 million copies sold) and its counterpart The 365 Smartest Things Ever Said. They also do a podcast with NPR's KMUW called You're Saying It Wrong.