Grand Stories in Grand Hotels: A Reading List

From Boarding Houses to Pensiones Peter Cameron

Recommends His Favorites

Two of my books are set in grand hotels: the Hotel Excelsior in Andorra (1997) and the Borgarfjaroasysla Grand Imperial Hotel in What Happens at Night (2020). I like checking my characters into hotels because it removes them from the familiar trappings of their home environment, and exposes them in a strange, more revealing light. And hotels are, almost by definition, transitional spaces, places where people have experiences that often send them subtly (or markedly) altered back into their quotidian lives. I think my predilection for grand hotels is simply a matter of scale, for the bigger the hotel, the more operatic the effect. Entering the lobby of a glamorous hotel is a performative act: we may only be an extra, but we undoubtedly are on stage. And so we play the role of ourselves, rather than being ourselves, and this often leads to trouble.

I think for this reason there are many novels set in hotels. Thinking about all of this prompted me to peruse my book shelves in order to locate and remember some of the books I own and love that are set partially or completely in hotels:

*

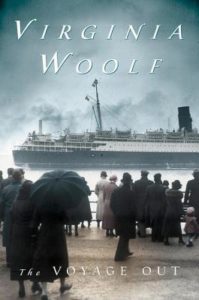

Virginia Woolf, The Voyage Out

The Voyage Out, Virginia Woolf’s first novel, published in 1915, is set in an unnamed South American country. A group of charmingly eccentric English people have crossed the ocean to spend a season at the only hotel in the coastal city, a former monastery that has been genteelly converted to comfortably host secular inhabitants. In a time-honored tradition, Woolf uses the hotel to gather together a large cast of characters and force them, by proximity, to interact. They dine and dance and even make a group excursion to a mountaintop. At the center of all these people and activities are Rachel Vinrace and Terrence Hewet, and the tender story of their first love. The Voyage Out is a unique fever-dream of a novel, sunny and languid until, in its final pages, a dark shadow falls upon Woolf’s conjured South American paradise. (Woolf enthusiasts will be interested by the cameo appearance of Richard and Clarissa Dalloway among this book’s hotel guests. They are nascent, not fully formed characters who will wait ten years—until 1925—to inhabit a book of their own.)

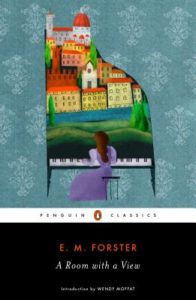

E. M. Forster, A Room With a View

In A Room With a View, E. M. Forster’s second novel, published in 1908, he similarly uses a hotel to assemble his characters, in this case English people visiting Italy. The room in question is in the Pensione Bertolini in Florence, and the view is of the Arno River. Somewhat miraculously, in one of the most delightful coincidences in English literature, most of the characters land within a few square miles of one another when they return to England. In tone and plot, A Room With a View inhabits a similar fictional world as The Voyage Out—both books revolve around young women muddling through their first experience of love, and explore the effect of foreign cultures on English sensibilities. Yet the geographical worlds of the books could not be more different: Forster’s evocation of Florence is beautifully detailed (he had obviously spent some time there), while Woolf’s South America is wholly invented. She had obviously never been there, as Forster noted by observing: “[A Voyage Out] is a strange, tragic, inspired book whose scene is a South America not found on any map and reached by a boat which would not float on any sea.”

Elizabeth Taylor, Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont

Mrs Palfrey, a genteel English widow who is running short of financial resources, sells her home in the countryside and checks into the Claremont Hotel in the first sentence of Elizabeth Taylor’s penultimate novel, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, published in 1971. The Claremont, a second-rate London hotel, is mostly inhabited by monthly tenants, all people who, like Mrs Palfrey, are maintaining stiff upper lips while teetering on the abyss. In this beautifully dark story of life’s final chapters, the hotel functions not as a place of temporary residence but as a place of last and final resort. Taylor’s description of the Claremont—the dowdy furnishings, the “dry, scorched smell” of the air, the unpalatable food—is scathingly precise, and her empathetic yet honest portrayal of Mrs Claremont is heart-rending.

Paul Bailey, At the Jerusalem

At the Jerusalem, a first novel published by Paul Bailey in 1967 (four years before Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont) covers much the same ground as Taylor’s better and better-known novel. In this case our heroine, Mrs Gadny, resides not in a hotel but in a hotel-like old-age home, where she has been shunted by her step-son (children do not redeem themselves in either of these books). At the Jerusalem unfolds mostly through Bailey’s brilliant use of unadorned dialogue. Mrs Gadny is less sympathetic than Mrs Palfrey, but her sad story is told with the same amount of empathy, especially remarkable given that Bailey was only thirty years old when his first book was published.

Denton Welch, In Youth is Pleasure

The idiosyncratically brilliant Denton Welch’s second novel, In Youth Is Pleasure, published in 1945, begins this way: “One summer, several years before the war began, a young boy of fifteen was staying with his father and two elder brothers at a hotel near the Thames in Surrey.” That boy is called Orvil Pym, but the character is really Welch himself, as in all of his autobiographically-based novels. The hotel is a classy place surrounded by a parkland with fountains and grottos, and, disturbingly, a pet cemetery. Orvil’s mother (like Welch’s) has died, abandoning her sensitive and artistic (and homosexual) son to the benign neglect of his cluelessly masculine father and brothers. In this case the setting of the hotel emphasizes the character’s displacement—as luxurious as it might be, it is not a home, and provides none of the comfort or warmth of a home. Orvil vainly tries to connect with other hotel guests and a disturbingly lecherous boy-scout leader who is escorting a troop of boys on an expedition along the river, but remains feeling alone and ostracized. At the summer’s end, he returns to his boarding school, another grand edifice where he does not belong and is not wanted.

Helene Hanff, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street, published in 1973, is a sequel to Helene Hanff’s earlier memoir, the best-selling 84, Charing Cross Road (1970), which chronicled the 20-year epistolary relationship (beginning in 1949) between Hanff, a brassy but erudite New Yorker, and Frank Doel, a refined London bookseller. A sort of platonic romance develops between the two book lovers, and in this book, set in 1971, shortly after Frank has died, Hanff journeys to London to meet his colleagues, widow, and daughter. Hanff stays at the “shabby-genteel” Kenilworth Hotel in Bloomsbury (“it’s going to suit me”), and the book is a charming account of the several summer weeks she spends in London. In this case the hotel becomes a temporary home-away-from-home, and the staff respond to Hanff’s unedited American friendliness by becoming part of her adopted English family. It’s interesting to note that, unlike fictional hotels, that never change, the actual Kenilworth is now a luxury 4-star Radisson hotel, and the casual shabby charm that so suited the down-to-earth Hanff has undoubtedly been replaced by a frigid hauteur.

Brian Moore, The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne

·

Patrick Hamilton, The Slaves of Solitude

Rooming houses are a poor relation to hotels, yet novels set in rooming houses are often more dramatic than those set in hotels, simply because the stakes are higher. Mrs Palfrey may feel somewhat humiliated by moving into a residential hotel, but she can still maintain her dignity by assuring herself that the carpet in her bedroom is “worn” rather than “threadbare.” But for characters who are forced by necessity into renting rooms in other people’s houses the situation is more dire and the challenges far greater. Miss Hearne, in Brian Moore’s The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1955) and (the unfortunately named) Miss Roach in Patrick Hamilton’s The Slaves of Solitude (1947) both live in boarding houses where their dignity and privacy are constantly undermined by the obnoxious behavior of landladies and fellow tenants. Unlike the affluent tourists in Woolf’s and Forster’s novels, Miss Hearn and Miss Roach arrive seeking not pleasure but succor and rescue, and are both undone by failed and final attempts to find romance.

J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

·

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

Two of mid-century American literature’s most indelible young characters found themselves checking into hotels and freaking out. In J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951), Holden Caulfield spends a harrowing night in his “very crumby” room in the Edmont Hotel surrounded by perverts, morons, and screwballs. And Esther Greenwood spends a “queer, sultry” July in the Amazon Hotel (a stand-in, I think, for the famous women-only Barbizon Hotel) in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963). On her last night at the Amazon, a defeated Esther climbs to the hotel’s roof and casts her wardrobe, piece by piece, over the parapet, watching as the “gray scraps were ferried off, to settle here, there, exactly where I would never know, in the dark heart of New York.”

__________________________________

What Happens At Night by Peter Cameron is available now from Catapult.

Peter Cameron

Peter Cameron is the author of eight novels (including Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You and Coral Glynn) and three collections of stories. His short fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Rolling Stone, and many other literary journals. He lives in New York City and Sandgate, Vermont.