Grace E. Lavery: You Already Write How You Write, Just Give In.

“The freedoms on the other side of self-surrender are much more interesting than those that require egoistic management.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

The essay that shifted me from the “promising kid” to “young upstart” category, and almost deposited me prematurely in the “overrated incontinent” bin where I presently dwell, was a scholarly essay about a book collector named Mikimoto Ryuzo. I had become vaguely obsessed with this person, and spent a couple of months tracing his steps around Tokyo, where he lived until the Second World War, and returned home with a sheaf of documents, mostly fairly banal cover sheets, copies of the front matter of some honestly-not-very-rare editions of Ruskin, unconvinced that I had anything to say.

I showed them to my advisor—it was the summer, and he invited me to his house, and sat with me patiently, seemingly honestly impressed (or maybe even moved!) by my haul. To him, it seemed obvious that there were things to say about the documents—things about embodiment, desire, sexuality, history, race, violence—and that there was relatively little to do other than some light annotation, and I was on to a winner. I left his house feeling excited to open up my laptop and start writing.

Twelve months passed, and I had written nothing. Most days I would feel guilty, unsure, clogged. Deadlines given to me for the sole purpose of incentivizing my writing came and went—who, in their heart of hearts can really abide by such a deadline, unless they already want to? At some point, an external deadline reared its head—it was connected to the absolute despair at feeling unrecognized I felt as a grad student—and I planned to get my work done, to write a ten thousand-word dissertation chapter, start to finish, in a weekend.

I planned accordingly: when Thursday came around, I bought two cases of IPA, and saved up a bunch of Klonopin in case I needed brief bursts of sleep. (I am an alcoholic and a drug addict.) I started drinking on Friday morning, and by mid-afternoon was on the Klonopin: the goddess of benzodiazepines blessed me, however, and rather than lull me to a deep and brief sleep, triggered an unexpected hypomanic episode, which carried me through for seventy-two hours without sleep, and left me, bright and early on Monday, with eleven thousand words of prose, and a couple of beers left for later.

I’m aware, of course, of the nightmarish banality of confessions by alcoholic writers. Blokey and brutish, the alcoholic writer seems himself as both glorious and abject, a seer for the ages, yet ensconced within the working man’s bosom, or at least his barroom. There are a few alcoholic writers I love—Guy Debord and B.S. Johnson, e.g.—but the famous ones—Ernest Hemingway and Charles Bukowski—are not my flavor. Nor, really, is the lesbian version of hard-drinking acidity—Patricia Highsmith, Elizabeth Bishop—one that appeals to me. I guess I don’t like American alcoholic writers. I mean, I get it, but…

Some of my very favorite writers—George Eliot, especially—are those who dissect with precision the power and charm of the alcoholic’s delusive self-conception. Still, I’m not immune to such delusions, obviously enough. And if one wants to tell the story of how one writes, which, god knows why one would, one is obligated to surrender the fantasy of having anything new or interesting to say.

I have never killed a darling in my life. Omg, can you imagine? It’s darlings all the way down. If I killed the darlings, there’d be nothing left.

I’m an alcoholic writer. Did I mention that? I wrote an academic essay in a weekend; it was good; it won a prize; it was awful; I can’t read it any more; I was proud of it; I was ashamed of it; I wanted everyone to read it; I wanted it withdrawn from circulation; I felt that I had said something true about the world; I felt that I had shaped some lies in order to make myself sound clever. My advisor was proud of me, and I wanted to thank him, because without his enthusiasm, there wouldn’t have been anything to write.

When I told him about the Klonopin, hypomania, and booze, he told me that it was an interesting story, but I couldn’t ever tell anyone—“at least until after tenure.” I didn’t. I pretended, as we all do, that writing was for me a discipline: write a little every day; don’t let composition run too far ahead of research; kill your darlings; trust your editors. I do none of these things. I have never killed a darling in my life. Omg, can you imagine? It’s darlings all the way down. If I killed the darlings, there’d be nothing left.

At a certain point, I stopped lying about my own writing practice, and about my own drinking. When I took my last drink, my most recent drink, just over seven years ago, I realized I had literally never written sober. As a high school student, I wrote my GCSE and A-Level coursework with a bottle of Smirnoff Black and a thing of Ocean Spray (purely for the purpose of camouflage) on the desk. I’d never had sex sober, either. Hungover, yes. I was very frightened that I’d never be able to write again, a fear I communicated to another alcoholic who didn’t drink, and he said “yeah, probably not. Most people don’t.

In any case, if you are serious about staying sober you can’t assume you will.” After a few months, I told a couple of senior colleagues that I was sober. One of them told me he’d been sober for twenty years, and his writing never came back. This guy was a successful academic who, as so many do, stopped writing after his second book. “My work was just so much worse than it used to be, I couldn’t stand it.” I loved him for that.

I don’t know how my students write. Probably some of them write a little every day, etc. I know some people do, and I envy them. Someone once told me that being around me while I was writing was like watching someone vomiting convulsively. I don’t recommend it, either the writing or the watching. If you can write a bit every day, probably best to continue writing a bit every day. I don’t know, though. Who does? Maybe having a hypomanic episode would help. It seems unlikely, but…

A thing I’ve learned teaching graduate students—literally, some of the smartest people in the world—how to write: writing is, indeed, pathological, but the pathology dwells not in the symptom but in the attempts to treat it. People who write like me try and fail to write like my advisor. I’m sure he wants to write in a different way too. We sit at our laptops and procrastinate—misleading word, the clinical term is “resistance”—and try to push something out that doesn’t want to come. It won’t until it does. We nurture our perfectionism—the clinical term is “anxiety.”

We can’t control our readers and some of them will hate us, and not because they misunderstand but because they understand perfectly. I dislike some perfectly good writers. I mean, who dislikes Elizabeth Bishop? Perhaps this all sounds like romanticism—perhaps it is. But when a student asks me how they should write, I have only one response: you already write how you are going to write. Stop trying to correct yourself.

The freedoms on the other side of that self-surrender are much more interesting than those that require egoistic management. You can pastiche other writers; you can stuff your prose with darlings—who cares, find your bliss! Most importantly of all, you can relinquish the fantasy that there is a form of good writing that is different from having something to say. There isn’t. Have something to say, and say it. That’s it.

When I had post-Covid brain fog, I wrote a book in two weeks, without really getting out of bed. I have almost no memory of that. I read it back the other day, and I kind of liked it. It’s a lovely feeling to be able to treat the writing one has produced as a kind of gift you give yourself—primarily, it’s a gift you give others, but of necessity you’ll never know how it feels to see your work from other eyes.

A few final things: one, just do your work. Most drama associated with people who call themselves “writers” or who are identified as such by others, is a form of procrastination, which is to say, resistance. It doesn’t really matter. If you can’t write, read. If you can’t read, do something else. Don’t force it—it might not come, but that’s fine too. Not everything needs to be written and not everyone needs to write.

Two, once you are professionally secure enough to risk sounding like a dick, be honest about how you write, whenever people ask. There are more of us vomiters out there than you think, and we have a responsibility to make life easier for those who believe that their writing habits will always hamstring them.

Three, editing is good but avoid the “we’ll fix it in post” mindset; it’s at least worth trying to get it right first time. I usually find that when I edit my own work, it gets worse. Other people edit me much better, for probably obvious reasons. Four, don’t let your composition run too far ahead of your research. Yeah, that one’s probably worth trying to keep hold of.

______________________________

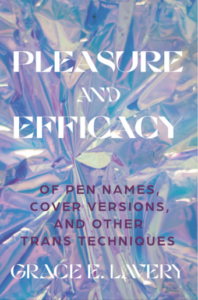

Pleasure and Efficacy: On Pen Names, Cover Versions, and Other Trans Techniques by Grace E. Lavery is available now via Princeton University Press.

Grace Lavery

Grace Lavery is an associate professor of English at University of California, Berkeley. A prominent public intellectual and activist, she has contributed to the Los Angeles Review of Books, Autostraddle, the New Inquiry, Them, the Guardian, Foreign Policy, and Slate. She’s been sober since January 2016 and “full time” as a trans person since March 2018. She lives in Brooklyn, New York. Her latest book is Please Miss.