Gorilla Under the Bed: Desire and Death in James Tiptree Jr.’s Her Smoke Rose Up Forever

Elizabeth Costello Considers the Socially Aware Subtext of a Pseudonymous Master of Speculative Fiction

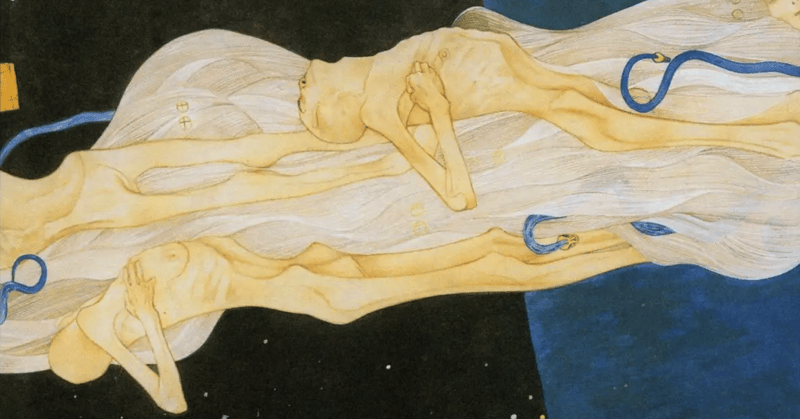

In her biography of James Tiptree Jr., Julie Phillips shares stories of Tiptree’s adventures in Africa as a child. Tiptree was one of the noms de plume employed by Alice Bradley Sheldon, who, in the 1920s, joined her parents on expeditions seeking specimens for the American Museum of Natural History. On her first such trip, the adults killed five gorillas, including a four-year-old. Six-year-old Alice slept with the dead child gorilla, preserved in formaldehyde, under her camp bed.

Presumably this arrangement had to do with available space in the camp, but as I read and admire Tiptree’s stories, I can’t help but return to this image of a child lying awake with another child, who has been hunted, killed, and preserved, under her bed. In many of Tiptree’s award-winning stories, a controlling, technologically advanced society provides thin cover for acts of violence and cruelty.

Beginning in 1967, Sheldon wrote as Tiptree for more than a decade, crafting a mysterious persona as well as award-winning science fiction that many critics and readers believed could not have been written by a woman. Whoever thinks that a woman can’t manifest grit, social anxiety, and technical expertise—both as a wordsmith in general and as a creator of “hard” science fictions—has a lot of reading to do. They could start with the story collection Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, which is jam packed with brilliant works that reveal something that no writer in any genre has ever disproven: the throughline of human experience is hubris.

We see what we want to see and are frequently unaware of how our desires shape our vision. Tiptree’s socially anxious fictions masterfully depict the irrational pull of desire. A Tiptree character might get on the road toward what they want, but they will not survive the trip with their presumed identity intact. In “And I Have Come Upon this Place by Lost Ways” and in another story I’ll discuss here, “A Momentary Sense of Being,” human beings are revealed to be ignorant not only of the planets they visit, but of their own motivations, which are rooted in desires that cannot be reduced to zeroes and ones.

Tiptree’s socially anxious fictions masterfully depict the irrational pull of desire.

In “And I have Come Upon this Place by Lost Ways,” Evan Dilwyn, an “anthrosyke” assigned to a ship that is touring the galaxy to gather data, keeps telling himself that “the computer has freed man’s brain.” The phrase is italicized, it is clearly something he has been told his whole life, a foundational assumption of the society he lives in. But like many of Tiptree’s characters, Evan has doubts about the wisdom he’s been told to receive. He is in an argument with himself—he can’t stop rejecting the tenets of his society, which has been so technologically successful that it no longer needs to be curious. He is wrestling with petty concerns about his position, when through the ship’s portal a mountain calls to him like some Siren drawing ships to their doom:

“On the far side of the bay where the ship had landed a vast presence rose into the sunset clouds. The many-shouldered Clivorn, playing with its unending cloud-veils, oblivious of the alien ship at its feet. An’druinn the Mountain of Leaving, the natives called it.”

The many-shouldered Clivorn! What is this creature, playing with its cloud veils, revealing and obscuring itself like a dancing Scheherazade? With a deft defamiliarization, Tiptree dispenses with postcard scenery, the mountain is first an autonomous being immune to our frames and lenses. There is another shift in perspective in this paragraph—a reader is reminded that Evan and all the scientists he travels with are the aliens here. They do not know what they do not know. They certainly do not know the meaning of the Mountain of Leaving.

Evan wants to touch the mountain, the Clivorn. He wants to use his “feeble human senses,” to feel it with his hands. When he learns that the ship is scheduled to depart the next day, his desire begins to overcome his societal programming. He is also undeniably inspired by Foster, the previous anthrosyke, who left his role under a cloud. At one point he hears a recording of Foster referring to the “Computer of Mankind” to which all the Star Ships send their findings, as “a planetary turd of redundant data.”

At a dinner under soft lights, Evan’s superiors make fun of Foster, while admiring the crystal “soul boxes” he extracted on a previous planetary visit. Foster had bought the boxes from the “newtwomen” who seem, to the sophisticated scientists, not to have understood rudimentary commerce. They joke about the decontamination job that was required after the newtwomen clawed at Foster, trying to get him to take them along as he returned to the ship. But they were their soul boxes, Evan insists, they were fighting for their souls.

The ship is a glamorous place where scientists from different planets dine on delicious foods and amuse themselves with games that are described in terms both light and menacing. In this story and in many others, Tiptree writes abuses of power into the social fabric. Walking through the ship after being chastised by a superior, Evan passes “three scared-looking Recreation youngsters waiting outside the gameroom for their nightly duty. As he passed, Evan could hear the grunting of the senior Scientists in final duel.” Tiptree never says what, exactly, goes on in the gameroom, but gives this reader feeling of uncomfortable complicity in a system that would make young people fear their nightly duty. The grunts salt the point home.

As an “anthrosyke,” Evan is at a bottom rung of the top section of the social ladder. To input his research into the program of the Computer of Mankind, he must use the program’s language, which allows him twenty-six nouns to describe his cultural/linguistic/social/psychological findings on other worlds. His colleagues in the hard sciences, such as the biologist who found the enzyme considered to be the only thing of value on the Clivorn’s planet, have more than five hundred nouns at their disposal. The language of the system that employs Evan is inherently exclusive—there are simply no such things as those outside its parameters.

As in our own society, decisions about language reflect and create systems of social control. People in power aim to stay that way by choosing what is and isn’t named. In Evan’s world, Science suffocates curiosity. As his superior Deputy Pontgreve says, “Science must not, will not betray itself back into phenomenology and impressionistic speculation.”

If Evan wants to learn more about the Clivorn and the mysterious line he sees near its summit, he will have to pay for an additional scan. The society he lives in claims science as its highest value, but its social and economic hierarchies crush creativity. Evan argues with himself, why can’t he be like the others who “never went out of seal, they collected by probes and robots or—very rarely—a trip by sealed bubble sled.” The Clivorn beckons to him through the portal, its clouds revealing and occluding the line that seems to cut across it near the summit. It seems to him to be something built, something, in his understanding, outside the technical capacity of the planet’s indigenous people. He spends the last of his available credit to buy a deeper scan of the area, a risk that he can take at his rank, but one that, if he’s wrong, will ruin his career. It does. The scan returns nothing, but the stakes become clear to him. He wonders if he is “even alive, locked in this sealed ship.”

Before he can be punished for following his “impressionistic speculation,” Evan takes a bubble sled and goes to the planet. When his superior demands that he return, he sends the sled back on autopilot, knowing full well that none of his colleagues will follow him. Walking into the village he meets the members of the local tribe who live at the foot of the mountain, engaging them with the few awkward phrases of their language that he has learned. Unlike him, they are a people tied to a place. As he goes up the mountain, they call after him, and one throws a spear at his leg. Whether they are warning or attacking him remains unclear—Tiptree keeps the action ambiguous. Evan himself does not understand what is happening. The language of the story changes, giving over to lyric and dream logic “There rose in him an infinite joy, carrying on it like a cork his rational conviction that he was delirious.” He comes face to face with a tiny flower, he discovers that the line he saw is real, it is the boundary of an energy field that can be approached by “Only a living man, stupid enough to wonder, to drudge for knowledge on his knees.”

Written in 1972, this story is resonant in our current days of data-enchantment, our delusion that data itself, devoid of context and purpose, can be a portal rather than a mirror. We are living in a many-mirrored age, in which we have so many ways to comfort and confuse ourselves with images. Tiptree and other writers of speculative fiction are well positioned to spool out scenarios that go beyond the personal and peer into the mechanisms of our oblivion. Evan runs towards his not-being but does not regret his choice to give up the cozy comforts, to trade the screen for a window, to open the window and crawl out on a wind-blasted ledge.

Weighing in at roughly eighty pages, “A Momentary Sense of Being” is a long and occasionally messy story that begins and ends with a dream. In the opening sequence a “parsecs long phallus throbs…under intolerable pressure from within…In grief it bulges, seeking relief.” We begin with desire so big it fills parsecs, but Tiptree tells us that grief underlies the great drive to make. The dreamer is Dr. Aaron Kaye, a physician and psychologist on the Centaur, a ship that has been away from Earth for ten years seeking another habitable planet. With characteristic indirection, Tiptree gives us an intermittent flow of detail about what has become of Earth—it’s not good, even for those at the top of the hierarchy. As Aaron presses the button to get himself a cup of “brew,” he wonders “What are they eating there now, each other?”

When the story begins, Aaron’s sister Lory, who is also a scientist, but one who focuses on plants rather than people, is being interviewed by the ship’s leaders regarding her recent return from a planet brimming with plant life. I’ve read that Tiptree/Sheldon was a fan of Star Trek, but her fiction refuses the temptation to simplify barriers such as time and space with the-future-will-solve-it tech such as a transporter beam. Tiptree gives us the mechanical grit—the movement of turbines, the spin of the ship, the direct experience of different levels of gravity, the challenges of growing food in space.

After leaving the other members of the scout ship crew behind on the unnamed planet, Lory had to travel alone for a year to return to the Centaur. The landing crew is unable to communicate directly with the ship. When the Centaur decides to signal to Earth’s inhabitants to pack up and move to the supposed Eden Lory has found, the transmission will take four years. Such impediments serve the plot—the crew of the Centaur can’t see what’s happening on the surface of the planet in real time. They are in the dark about their past, the story of life on Earth that has continued to unfurl without them, and, based on the poor results of ten years of habitable planet searching, their future has seemed nonexistent. The new planet, throbbing with bioluminescent plant life and breathable air, seems a dream come true.

The story is told in a close third person, we see the world of the ship through Dr. Aaron Kaye. “Here we are,” Aaron muses, “Tiny blobs of life millions and millions of miles from the speck that spawned us, hanging out here in the dark wastes, preparing with such complex pains to encounter a different mode of life.”

As Tiptree, Alice Bradley Sheldon calls us out as the animals we are, despite our shiny thin metal skins of rationality and order and belief in our own technological prowess.

Tiptree’s life as Alice Sheldon included earning a Ph.D. in psychology and a stint in the CIA, background that surely informs the clinical authority of Aaron’s descriptions of his fellow crew members’ moods and facial expressions. He seems to be able to see himself and the others on the Centaur with a measure of dispassion, even recalling and admitting to himself his incestuous relationship with Lory when they were adolescents.

Yet he remains attuned to Lory’s presence in a way that seems inextricable from their shared sexual experience. When she is being interrogated by the ship’s leadership he equates their aggressive questioning with rape—a reader learns later that he “ended both their virginities” when she was thirteen and he was fifteen. He is also attuned to the presence of the specimen Lory has brought back from the planet and begins to believe that the “sessile plant-thing. Like a cauliflower, like a big bunch of grapes” is causing him to have nightmares.

As a precaution, the “bunch of grapes” is at first kept in the scout ship, which is tethered outside of, rather than docked in, the Centaur. As he walks through the ship, Aaron feels the presence of the specimen through the metal skin of the ship. He is aware of the specimen in a way that feels menacing but is akin to the way you might be aware of someone you desire—you want to be cool, but you feel them enter the room. Your peripheral awareness catches their movement. He wants to remain aloof, to follow all the protocols.

Throughout the story he will try to maintain this distance from the desire that the specimen will soon unleash in his colleagues, causing them to abandon any semblance of rationality as they become part of a much larger mechanism of reproduction than they previously understood existed. Unlike Evan Dilwyn, Aaron Kaye stays in the struggle until the end of the story, becoming the lonely recorder of what might be humankind’s last ejaculation into the galaxy. In a recording he is making for the potential interest of science, he admits that he no longer dreams.

In “A Momentary Taste of Being” as in “And I Have Come Upon this Place by Lost Ways” desire and death are twins. The former draws us toward unfamiliar places, the latter remains forever under the bed, the unchangeable end of our changing organic bodies. As Tiptree, Alice Bradley Sheldon calls us out as the animals we are, despite our shiny thin metal skins of rationality and order and belief in our own technological prowess. In these stories and others in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, Tiptree offers us a more potent and troubling mirror than the ones we might craft for ourselves. Unless, of course, we want to consider the vastness of space, the relentlessness of nature, and the baroque interplay of our lust and our controlling, problem-solving minds.

__________________________________

The Good War by Elizabeth Costello is available from Regal House Publishing.

Elizabeth Costello

Elizabeth Costello has lived in Turkey, Spain, Mexico, France, and in several American cities. Her previous publications include the poetry chapbook RELIC and her collaborators include dancers, poets, and musicians. The Good War is her first novel. She lives in Portland, Oregon.