Good Ghosts and Bad Fathers:

The Story of a Haunting, a Kidnapping, and an International Incident

Helen Vogelsong-Donahue Finally Escapes Her Bogeyman

1.

I was being hunted.

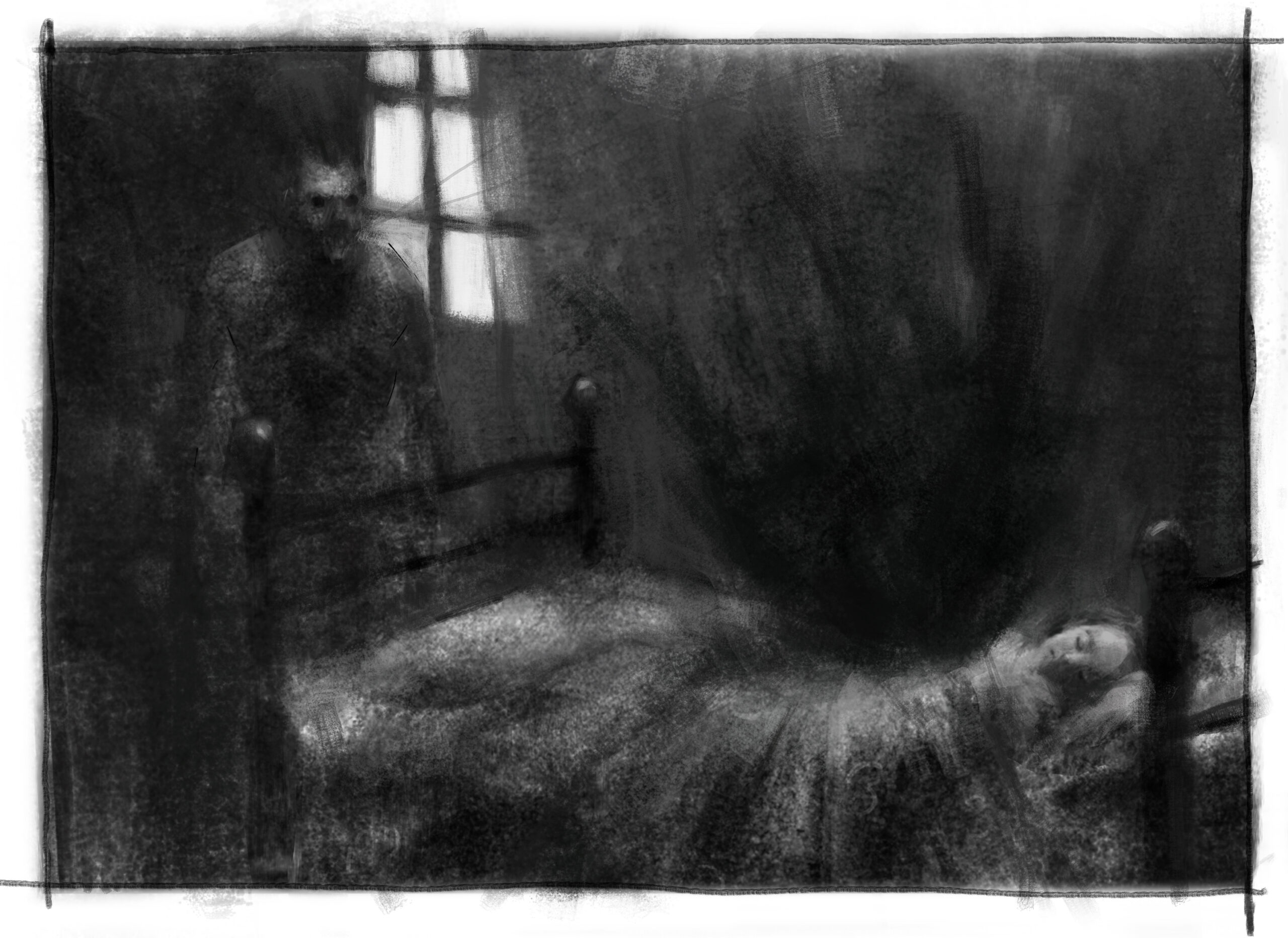

Each night, Mom locked our doors and windows like she was closing a restaurant in a bad part of town. Every lock checked twice, every night a gamble. While other five-year-olds were asleep, calmed by cassette tapes and their mothers’ voices, I was awake. What if tonight was the night he’d finally break down the door and kill me? Kill us all?

I imagined myself as the last to go, powerless to help Mom and my brother, Simon, as he hacked them into bloody bits before turning the axe on me. An axe, of course, was the most powerful murder weapon, and a necessary one: how else would he get inside the house?

Insomnia followed. I’d wait until everybody was asleep, then creep from my bed through the dark to the second-story window overlooking the road and—more importantly—the county jail on the other side. It was a grim, beige building—an austere and functional structure where decades previously—before a fire burned it to the ground in the 1950s—there stood a fortress-style prison studded with decorative turrets and watchtower battlements, the location of countless 19th-century executions, where criminals were hung from gallows in the courtyard and buried in unmarked graves, just a few steps away from the cemetery that stretched into the dark.

Sometimes, the blinds would be up at the jail, allowing me a glimpse into the strange world of corrections. The cops were usually eating donuts and, if I was lucky, watching television: Beavis and Butthead, The Simpsons—late-night cartoons too adult for me to watch. I tried to make sense of it: The police, the criminals, the fear on Mom’s face, the fear that he would find us.

Why were these men locked up, I wondered, while he was allowed to roam free? “They’re in there because they’ve done something bad,” Mom had explained once, studying my puzzled face as the inmates helped shovel snow from our sidewalks. Worse than him? How bad could they be?

I took some solace in knowing the police were only 30 feet away. Not that they’d ever been helpful—they hadn’t managed to stop him before—but I figured if he showed up here, the cops across the street would hear the heavy footsteps, the jiggling of doorknobs, the thwack of the axeblade in the night.

When I did manage to sleep, I had night terrors; my body would launch upright from bed and my throat would release a cry loud and terrible enough to wake Mom and Simon. She’d tell me my eyes were open during these parasomniac events, though I was otherwise unresponsive. I never remembered anything, though I wondered if I was witnessing something in that sleep state; that the screams were a warning that he was back.

Please keep us safe, I’d say, imagining them as invisible defenders, rising through the swirling mist like my own personal army.

I later discovered this was why we lived next to the jail. “I hope you’re enjoying the house,” I heard Grandma tell Mom: “I know it isn’t much, but it was the safest place we could find.”

When Mom was at work, Simon and I stayed with our grandparents on the family farm, a few miles outside of town. Grandpa would take me out for strawberry ice cream, to the lake, or on agriculture-related errands, often to check on the rabbits in the barn he’d built, or on farm-to-farm deliveries. I was terrified of any man who wasn’t Grandpa, cowering behind his legs as ancient farmers introduced themselves with calloused hands. Even when they were tender, I felt uneasy. But Grandpa kept me safe, with my little hand clasped in his, on walks through town, or through the woods behind the farm.

On the farm—where the occasional crack of a bullet in the distance was commonplace, especially during hunting season—Mom had the freedom to practice firing her gun, a 10-inch .357 Blackhawk revolver so long she’d bought a big purse in which to carry it. We never saw her shoot it, but she told us she sometimes used watermelons the size of human heads as targets. “In case he comes back,” she’d say, “I need to know how not to miss.”

At home, we did arts and crafts with empty cans that once held cheap nonperishables like chicken noodle soup, mixed veggies, and Vienna sausages. Strung together by twine, tin hugging tin, like metal hands across America, we’d attach the braided ends to the lifts of the first-story windows. If the Bogeyman were to enter, the cans would dance and clap their steel hands loud enough to wake us. Mom would then reach into her nightstand, where Grandpa had built a secret compartment for her revolver.

We tried not to talk about him. I didn’t know his name, just that we were in danger, and maybe always would be. To me, he was just the Bogeyman. And I’d spend the next two decades looking over my shoulder, waiting for him to return.

*

I was also being haunted.

When it rained, the boy in the basement came out to play. Simon and I called him Thomas. He didn’t like the rain the same way we didn’t like the basement: a damp, dark cellar that jerked cats and dogs into a frenzy at the top of the stairs, hissing and howling at the unseen below. Thomas often let his presence be known, but he was particularly demonstrative on rainy nights. Lights flickered, doors creaked and slammed, and I wondered if Thomas thought that if he shook the house enough, God would spare us the deluge of Pennsylvania thunderstorms.

When the clouds gathered, and the first drops started to speckle the brick in the backyard, I’d wait for Thomas to arrive. Sometimes the TV would turn on, flipping through channels, or a kitchen cabinet would fling itself open, or the faucet would run. I liked seeing Thomas display his powers. Maybe those powers would protect me.

The cops next door were supposed to make me feel safe, but they didn’t. I saw ghosts everywhere, and to me, they were our guardians. In addition to Thomas were the spirits from the cemetery across the street. There, spread across twenty acres, were thousands of Bellefonte’s deceased: Civil War soldiers, wrapped in a ring of graves called the Soldier’s Circle; three notable Pennsylvania governors; nearly one hundred unmarked infant graves referred to as “Babyland”; and a gorgeous inventor, suffragist, and WWI special agent named Anna Wagner Keichline, who was also Pennsylvania’s first woman architect.

Even those who are frightened by the idea of ghosts like hearing about them. They exist in every culture, pervade every language.

Mom, brother, and I would take long walks through the graves, and occasionally, Mom would point to one and have us try to read the epitaphs, sounding them out the best we could. I felt a kinship with the dead. I learned words and names and spoke to the buried soldiers. Under my breath, I’d request their help. Please keep us safe, I’d say, imagining them as invisible defenders, rising through the swirling mist like my own personal army. I decided if the Bogeyman ever showed up, they’d put the cops to shame.

It must have been one of these soldiers I’d seen standing watch over the house, garrisoned in front of our backyard’s converted carriage house with his hands clasped over the pommel of a long cavalry saber. I’d watch him from the kitchen, looking out the big glass door that opened into the backyard. I told Mom about him, reporting on his sentry duty. Nobody besides me could see him and I didn’t know if he could see me.

Kids see ghosts, they say. Or they have imaginary friends. When we’re young, our beliefs aren’t yet limited, distinctions not yet made. Even those who are frightened by the idea of ghosts like hearing about them. They exist in every culture, pervade every language. The idea of an afterlife allows us to bypass the existential dread of living, to imagine our deceased loved ones in pastures among the clouds, silently but diligently guiding us along our individual journeys. Tall tales keep the dead alive, because nobody wants to feel alone in the universe: human beings need ghost stories to survive, and every story is, in some sense, a ghost story.

Here’s mine.

2.

The Bogeyman was sitting in front of us.

I was four. And there he was, seated on a gray couch right in front of me, arms wide open. The Bogeyman. Would he disappear if I closed my eyes tight enough, as he often had in my dreams? Not this time. How did he find us? He was confident—arrogant even—and collected, smiling down at me, always so certain that he could trick me this time. Why was he smiling if he was there to kill me? His eyes seemed black and empty. He offered me toys stuffed in plastic shopping bags. I declined, although I badly wanted them. Mom could not afford many toys, and these were nice ones—baby dolls that cried real tears and an Easy Bake Oven that promised perfect brownies in 15 minutes.

The bogeyman looked like a malevolent marionette, his mouth tugged into a grin by an unseen puppeteer. It was a forced expression with no emotion masking a desperation to control. I knew he believed that if he could deceive me, he’d win. So, I hid with Simon under the table, gazing down at the floor. If I met his eyes, I would turn to stone like in my Greek mythology books, or worse, start to believe him. I kept my eyes down, staring—down, down, down—until the stiff, tufted carpet became just an orange blur.

When I finally looked up, he was gone.

That wasn’t the only time I saw the bogeyman. Every so often he’d come to this place, calm, devious, waiting for the moment to strike at us all. Again, I’d look down until he disappeared. This was how gazing at the ground became a habit, one that annoyed Mom and teachers, who yelled at me to watch where I was walking. “You’re gonna get hit by a car, Helen!” But my eyes fixated on my shoes, the sidewalk, the wooden floors. Down was safe. What if I look up and there he is again?

When Mom remarried, we left Thomas behind. Only a few streets over, our new home was much bigger, and for me it felt like a fairytale castle. A three-story Victorian with a big, tiered backyard and the ruins of an old carriage house in the back lot where sunflowers bloomed every summer.

The voice we heard was always friendly, and sounded close but far away, like he was speaking underwater.

The ghosts found me first. I’d smell perfume on the landing of the stairs, or smoke, strong and pungent as though blown through a pipe in the old drawing- turned-computer room. Late at night, when the rest of the house was asleep, I’d hear parties downstairs. Glasses clinking, music, and muffled laughter. I’d jump from bed to investigate, thinking it rude my parents would have a secret, late-night soiree without inviting me. But when I got to the banister, I saw only darkness. Once, I heard a woman crying downstairs, howling so much I thought it was the family cat being eaten alive—until I saw the cat run right past my doorway as the weeping continued.

The adults never seemed too afraid of the cabinets slamming or lights flickering. So, neither were me and Simon. Naturally, we feared what our mother feared: that the Bogeyman would find us, despite having moved; that he was out there right now, in the dark, looking in; that we were marked; that we were in danger.

I dreamed of a balding man with a graying beard standing in our drawing-room, puffing a pipe in a double-breasted jacket and gazing out the bay windows that overlooked the front yard. I dreamed of him so often I suspected he was there in the house with us and wanted something. I wondered if the affluent gentleman of my dreams wasn’t the same person who started speaking to me and Simon a few months later. The voice we heard was always friendly, and sounded close but far away, like he was speaking underwater. The volume varied, but he always asked the same thing: Where’s the book?

“Did you hear that?” Simon whispered. It was the first time we heard him. We were frozen in place, too afraid to drop the Beanie Babies we were leading into battle on his bedroom floor. Tom was on a business trip and our mom was outside doing yardwork.

Where’s the book? the voice repeated.

Simon and I exchanged a look. He was the big brother, and knew that came with check-the-house-for-ghosts duties. He tip-toed around the house in his bare feet, peered down the staircase, called “Hello?” from the foyer.

“Nope, no one here.”

“Maybe it was one of our Beanie Babies,” I suggested. We howled with laughter, imagining General Patti the Platypus talking to us.

When our mother came in through the back door, we ran downstairs to tell her the news.

“He just wanted a book,” Simon explained, trying to clarify that the Bogeyman was not in the house, just a harmless ethereal bookworm.

We called him the Book Man. Mom always listened intently to my ghost sightings and made sure I never felt disbelieved—but sometimes she couldn’t help but find it funny when her five-year-old daughter would charge in and declare yet another spectral visit. Once, when I was convinced I’d heard a baby crying in the night, I came downstairs the next day and accused Mom of secretly giving birth to a new sibling—the only semi-logical explanation I could think of—and she doubled over laughing. This time, she listened to our story with a smile. Most families moving into a century-old house, only to find it full of ghosts, would flee. But for us, ghosts were not the problem. Nothing haunting the corridors inside the house could be as dangerous as what Mom said was outside.

“Well, as long as he’s not back,” she said. “I don’t care who hangs out in this place.”

3.

The spirits of the house were interacting with me, they wanted my recognition. And while it was clear to me the ghosts knew I could hear them, it wasn’t enough: I wanted to see them, too. My power was growing, I was sure, because I was the only one experiencing most of our new home’s activities. What visual proof I could garner would solidify my status as Helen, Communicator with the Dead, through which I’d help protect myself and my family from the danger lurking just outside.

We weren’t living across from the county jail anymore, a fact I became more and more aware of as I lay awake at night listening to the walls and pipes expand and contract around me. The thing about old houses is they breathe, their walls alive with energy. I imagined the ghosts in our home as part of the energy, clicking and whirring around us like parts of a machine as we slept. They were the hands on the grandfather clock at the foot of the stairs, the engine of the house. The ghosts were necessary.

One such night, when I couldn’t sleep again—this time, not for the usual reasons, but because I’d accidentally swallowed a marble—something miraculous happened: The ghosts finally showed themselves to me. Always the catastrophizer, I was lying in bed paralyzed with fear over the marble, when suddenly, a night light illuminated the lavender wall opposite my bed.

Flush against the paint was a hand shadow, the kind I imagined kids might make at sleepovers. It began with simple shapes: a dog, a sheep, a rabbit. Then the shadows multiplied, transforming my room into a wondrous menagerie. I watched in awe as elephants, camels, and men in cowboy hats paraded across the room. They grew more elaborate, shifting into dragons, unicorns, and phoenixes rising from the ashes. It was so stupendous—such a marvel—that it took far too long for me to notice no arms were attached to the hands.

Socially, I was a strange case, with a house as my best friend. I was barely school-age, and already a goth in spirit.

Still, I was suspicious. I got up, mid-performance, to investigate the window beside my bed. Though not quite a skeptic in my youth, I figured what was happening was one of two things: the ghosts in my house were finally interacting with me, a sign perhaps of mutual respect, or someone was playing a trick on me at two in the morning. Expecting an “aha!” moment, instead, when I peered out the window to the house next door, the entire place was dark, and all the blinds were drawn.

The dance of the shadow puppets continued, whirring around the spotlight and morphing into creatures I thought impossible to replicate with one’s hands. It felt like it went on for hours. I was unafraid. The event was an adventure, a profound comfort—and, as I drifted off to sleep, a lullaby.

*

In my head, I was in constant negotiation. You protect me, and I’ll never let anything terrible befall this house. If neither of us could do anything about our current circumstances, the ghosts and I may as well have each other’s backs. The house was my safe haven, a sanctuary that, by fate, I’d stumbled into as its caretaker. My being there was kismet. I was just a living visitor. I respected the house. So much so that I’d often remove the small, gilded mirror from the downstairs bathroom wall and walk around just admiring the ceiling, the architecture of the home that’s taken for granted when you’re not looking up. Which, of course, I never was.

“Ghosts are just people who are dead,” I told my pre-kindergarten class as we sat cross-legged on the carpeted green floor of the casket room at the Victorian Crematory. Our daycare instructor had left something behind at her apartment—something she apparently desperately needed—and dragged us along with her in an attempt to find it. The caveat was she lived at the borough’s only funeral home. She led us up the street from the YMCA to the crematory in buddy-system, attempting to make the trip educational once we arrived by giving us a tour of the cremation room, in it a big, silver machine that charred dead bodies to such a crisp the funeral director could scoop up the chalky ashes and return them to their families in a decorative urn.

I was scared—the air in the funeral home reeked of chemicals and all-purpose cleaner, which only confirmed the amount of death around us—but I was also intrigued. I’d only lived with ghosts; I’d never seen a dead person before. I was realizing fear is fun when you feel safe: I loved hearing the wood creaking and pipes clanking in our house in the dead of night, listening to Mom read Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark to Simon and me, watching The Nightmare Before Christmas every Halloween, and, now, taking field trips to spooky locations.

In the casket room, Miss Kristy asked us if we had any stories we wanted to share about death. I did not, but every other kid seemed eager.

“My uncle died skiing,” a kid called Joel said excitedly, explaining how his uncle had run head-first into a tree and BAM, lights out! Miss Kristy looked stricken. She tried to change the subject. The well-varnished caskets gleamed under the lights.

We left the Wetzler funeral home, but it did not leave me. An obsession with death—and the dead—was growing.

At school, they called me Ghost Girl because of my constant testimonials about the supernatural. I regaled everyone with vivid accounts of what I’d seen floating down the stairs, or what I’d heard going bump in the night. I didn’t care if anyone believed me: I felt special. No one else could see the ghosts.

In the dead of night, with the proverbial chains rattling in the attic, I became more relaxed and at ease. My comfort with what frightened others released some of the anxiety about what really frightened me. Fear is fun when you’re safe, but we were still not safe. The Bogeyman kept coming back. He was a constant dread, a low hum that came in through the walls, a chill in the floors.

But the big Victorian house, whose ghosts frightened the neighborhood kids, welcomed me as the ultimate refuge.

I declared to myself that I would live there for the rest of my life. I was a spooky little child making promises. I’d never let the red paint on the front door chip, or the ornate white gingerbread trim rot off the gabled roof. I’d stand like an apparition in the dormer windows. I’d water the poisonous foxgloves, pick the weeds from the carriage house ruins, and leave food out for the stray cats. I’d reupholster the tapestry cushions and dust the walnut fixtures, which I’d polish with olive oil and white vinegar twice a month. This house would never fall into disarray like the one down the street, the one that Simon and I would dare one another to approach—the abandoned one with the peeled pink exterior and broken windows.

I whispered to the house, alone but content, watching life come and go through the neighborhood. Socially, I was a strange case, with a house as my best friend. I was barely school-age, and already a goth in spirit. I longed to be feared. I was still living by the cemetery when I decided I wanted tattoos and piercings after seeing a girl with jet-black, box-dyed hair and eyebrow rings dressed in black walking through the graves. Her fingernails were long and streaked. Her steel toe boots sat on a four-inch wedge. Her delicate fingers, shining with silver rings, ran along the headstones. She wore a dog collar, a leather strip viciously spiked. She looked like someone no one would like. I’d never seen anyone so beautiful in my life.

At school, my reputation as Ghost Girl grew. Classmates were intrigued. They’d see me drawing goth girls and spooky cryptids—three-headed beasts, ghouls, and vampires—in my notebooks all day, and sometimes I’d hear them talking about me.

One day, a kid at recess approached me nervously, like he’d been dared to. I thought he’d want to know about the ghosts, or make fun of my unibrow, or stand there frozen and then run away.

Instead, he asked me a question:

“Aren’t you the girl who was kidnapped?” I didn’t want to admit it. But I did.

“Yes.”

He had a smile on his face, the glee of having discovered something taboo, unfamiliar, and, most incredibly, true. Then he added:

“By your father?”

I really did not want to admit this. But I did.

I was used to this question. Because it was true.

4.

I didn’t know his first name, or where he lived, or where he’d lived with Mom, or why she’d loved him, or how she could. I didn’t know if I was a mistake, if she’d wanted me, or if she’d only wanted Simon and I’d been an unfortunate accident. I always felt like one. I didn’t know if I reminded Mom of him or if she saw his face in mine when she looked at me. I barely knew his face myself.

Mom grew up bookish and carefree, an artistic child who, like me, didn’t know her biological father. By her tweens, she was well-read in Shakespeare and Chaucer, which she preferred to boys and clothes, hair or makeup. She majored in English at Penn State and backpacked across Europe before deciding to pursue graphic design.

She was in her mid twenties when she met my father. They both lived in the same apartment complex. She worked in advertising, illustrating campaigns for airlines and fast-food chains, and he was a cabinet maker on a student visa from Iran for dentistry. He was only a few years out of compulsory military service.

It was 1987 and the Ayatollah Khomeini’s grim scowl was often on the 6 o’clock news. But my father was handsome and disarming. And persistent. He brought her flowers and called up to her on the second floor whenever he walked by. He had a nice smile and spoke broken English. He was handsome and well-liked. Until they knew him.

By the time my father arrived, he was greeted by a phalanx of farmers, shotguns in hand. While Mom huddled inside, my father growled and fumed and was eventually told by police to leave.

It’s hard to imagine now, but theirs was a swift romance. Mom, who hadn’t dated much in her twenties, was naive to his charms. They were engaged within a year, and he conceded to a marriage at an Episcopal church rather than a mosque. The reception was, by all accounts, awkward—on one side, rough and tumble Pennsylvania-Dutch and on the other, Tehran natives, many of whom could not speak English. She gave birth to Simon in 1989, then became pregnant again with me less than a year later.

The marriage quickly turned abusive. My father isolated Mom, for control. He refused to let her talk to her parents and intercepted mail from friends. Outsiders were a threat. He became physically abusive. Mom would call the police, but he would charm them too, warding off the authorities, always with a story about a hysterical and jealous wife who kept bothering the poor police, who surely had better things to do. But his abuse of Simon eventually brought Simon to the pediatrician, where he was diagnosed with “failure to thrive.” There, the doctor issued a stern warning to Mom and said he’d call Child Protective Services himself if she didn’t leave my father for good. She’d been plotting an escape in her mind for some time, but this pushed her into motion.

It was in the middle of the night when she quietly gathered up Simon and me, slipped out the door, got us into her gold Toyota Camry, and fled. She stopped at a gas station around the Mason-Dixon line and dialed home to tell her parents we were on the way. When Mom arrived, my grandmother later reported, she barely recognized her.

My grandfather was out of town when we arrived, so Grandma called the neighboring farmers to put them on alert. She thought my father was likely to follow. She was right. Later that night, one of the farmers called with the news that he’d spotted the bright lights of a car penetrating the elemental darkness of the Pennsylvania countryside. By the time my father arrived, he was greeted by a phalanx of farmers, shotguns in hand. While Mom huddled inside, my father growled and fumed and was eventually told by police to leave. He took the car, and we remained safe in Grandpa’s study, among the toys and books and trinkets that smelled like home.

*

Mom filed for divorce, and in the midst of the custody battle that had her driving back and forth from Bellefonte to Fairfax, Virginia for weekend visits, my father entered the Iranian Embassy in DC—cute baby photos in hand—asking that Simon and I be added to his passport. They obliged. Mom realized something was wrong when she called his house for three days and no one answered.

She knew where we’d gone—he’d threatened to take us to Iran many times before. She’d told the police about his threats to no avail. My father had instead convinced the judge to allow unsupervised visits, a testament to his charisma. And then, we were gone. It was August 12, 1991, my first birthday.

After months, our kidnapping had become an international incident. There were negotiations with lawyers and government officials. Switzerland got involved.

Mom—32 and penniless—began a letter-writing campaign, and placed posters she’d assembled by hand in local businesses urging people to call their representatives. They did. Mom petitioned her senators. Local news covered her plight. Somehow, she convinced the FBI—though she doesn’t remember how she got through the door of their Fairfax office—to create a case for us and assign an investigator. Sometimes my father called from Iran, offering to let her speak to us. Sometimes he asked for money. The FBI tapped Mom’s phones, but the calls couldn’t be traced.

After months, our kidnapping had become an international incident. There were negotiations with lawyers and government officials. Switzerland got involved. That’s how you know you have an international incident on your hands. My father actually despised Iran and probably didn’t really want to be a real parent, so he negotiated, using us as bargaining chips. Eventually, an agreement was reached, and we were returned on November 18, 1991. It was Thanksgiving Day. This is why my family always celebrates two Thanksgivings—the one on everyone else’s calendar, and another on the date of our return.

Astonishingly, the Iranian government granted the United States permission to extradite my father, as long as he was exempt from prosecution. An immunity deal. He returned to Virginia, where, after the six months he’d spent on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, my father’s record was cleared, and he walked free—and straight into a new custody battle with Mom.

He had no interest in winning. It was a battle of spite. En route to our heavily supervised visitations at the Centre County Children & Youth facility, we had a police escort. Our mother was not allowed to be present, so a social worker would accompany us as we were forced into a windowless room for our monthly, court-mandated hour with Mr. Z.

*

I didn’t know any of this, of course. Simon’s first memories are in Iran, but I was too little. I don’t remember my father from that time at all. All I knew was the mysterious entity Mom called Mr. Z., who I thought of as the Bogeyman. He was an intimidating, lingering presence in our lives, the thing that kept me awake at night, hiding under the covers. In his physical presence, I trembled, trapped in dread, turned in on myself. In his absence, I had nightmares about him.

Once, I’d had a string of dreams for months where I’d been buried alive, unable to speak, move, or see. I sensed darkness, muck, the writhing of earthworms. Like so many graves I’d walked above in the cemetery, I was in the ground. And I could hear him laughing. I woke to skulls dancing around my room. And the Bogeyman was there, amid them, dripping with wet mud and crawling bugs. And then he vanished, and everything was calm.

Sometimes, he would send us birthday cards, which Mom intercepted. During our visits, he always plied us with toys and sweets, which we knew to reject, because our mother made sure to remind us before going in that the Bogeyman was a liar.

It was during one of those strange moments, trapped with him, that I recognized my first lie. I was trying not to look at him and not eat the candy strewn about the floor, when Simon broke the silence, and looked up at him angrily. “You kidnapped us,” he said. I didn’t quite understand, but felt protected by Simon’s uncharacteristic display of fierceness, the most confrontational I’d ever seen him, before or since. The Bogeyman looked back at his children, incensed. “I did not kidnap you,” he said, forcing a smile and through gritted teeth.

“Your mother did.”

5.

After the kidnapping, Mom was destitute. She’d left behind everything she had, and that wasn’t much to begin with. She took on substitute teaching, but that wasn’t enough. We had no furniture, and ate all our meals on the floor, a perpetual grim picnic. Our clothes were all donated. Our gifts were wrapped in newspaper, and our Halloween costumes were made of cardboard.

Eventually, Mom got sole custody of us. After the fact, Mom learned my father tried to hire someone to kidnap us again; a cousin of my father had called Grandpa to warn him, and he informed the judge. This is why our meetings were reduced to hourly supervised visits. For years, my father clung to some rough semblance of fatherhood, aware if he slipped up and failed to contact us for six months, Mom could petition to overturn his parental rights. He sent Simon and I birthday cards in the mail every year—though Mom intercepted them—and checked in for visitations occasionally, until the meet-ups grew further and further apart. Eventually, he stopped visiting and sending cards altogether, at which point Mom argued in court that his parental rights should finally be revoked. She won.

When I felt unsteady, I would sit quietly in my room and listen for my ghosts. They were always there for me.

Though life became relatively normal Mom’s revolver was always nearby. And every time me or Simon moved schools, she’d turn up with a dossier on my father, a collection of clippings, court documents, and photos, explaining that a man named Naseem Z. may appear and claim custody of us, and if he did they were to act fast.

Sometimes Mom tried to pretend not to be scared by Mr. Z. anymore, but then I would wander over to the neighbor’s house to play with her Airedale terrier and eat freshly baked scones, and stroll back a half hour later to find Mom and Simon screaming my name from the porch. On this occasion, she was crying, and Mom does not cry. I hurried inside, shaken. As I went upstairs to my room, I felt the ancient, sturdy banister and admired the domed newels of the staircase. The sun scattered shapes on the stairs.

When I felt unsteady, I would sit quietly in my room and listen for my ghosts. They were always there for me. And I for them. I loved their murmurs, whispers in solidarity. After all, the true threat was the real world out there, not the spectral bustle inside. Downstairs, as Mom recovered, I pressed my ear to the walls, calming myself in the hush of my beloved haunted house.

6.

Eventually, we moved. Mom’s new husband Tom got a better paying job in Texas, and so we left our Victorian house. It had been years since Simon and I had our murky encounters with Mr. Z. And we’d long since known that he was the Bogeyman, and the Bogeyman was our father. But now, any rustling we heard outside in the night was just the stray cats we fed on the back porch. No axes came through the door. The Bogeyman never made it inside the house. I mourned the loss of the Victorian house, and its vigilant ghosts, the only thing that made me feel safe, and special. The day we left Bellefonte, I put my hand to the house’s old damask wallpaper and promised one day I’d be back.

In our new life, I felt uprooted, unnerved. We landed in a new and decidedly un-haunted home in the Dallas suburbs. The place I’d grown up was a tiny, beguiling town, with history, rimmed with stone architecture and mossy mountains. We moved into a flat, sterile landscape, the fastest growing municipality in the country, an array of prefabricated chain stores dropped into the dusty plains. I’d been frolicking through a century-old house filled with friendly ghosts, and our new house in Dallas was a charmless box. We were no longer a short drive to Grandparents; they were now a plane ride away. I mourned the place we’d left behind. I was 10 and it felt like I had gone to another planet.

Not long after that, my grandfather was diagnosed with stage four cancer. He was just 60. I felt like we were being punished for leaving the Victorian house behind; no longer safeguarded, we were exposed.

Among the kids, I was popular. I didn’t fit in anywhere exactly, which allowed me to sort of fit in everywhere.

By the time we flew back to Pennsylvania to see my grandfather, he was withered and frail. He looked so small and bony in his new body, his skin jaundiced to such a yellow that I was afraid he might stain the white hospital linens. He was cursing a lot, and it was kind of fun to hear a pastor curse. Shit, fuck, damn! Grandma didn’t want to leave his side. She always smelled wonderful, like her handmade soaps of lavender and lye, but now she looked exhausted, her thick, gray hair pulled up in a lazy ponytail. Mom kept pushing her out of the hospital and into the car, back to the farm: “You need to eat, mom.” Grandpa wants to eat, but can’t. Solid foods were off the menu. “All this jello,” he scoffed. “So much fucking jello.”

*

By this point, I didn’t even know what my father looked like. This was part of the fear. I was at new schools, where no one knew our small-town lore. Would I recognize him if he approached me? Would I be an easy mark? Would I not see him coming? Or worse, would I see him at last and realize that he looked just like me?

I quickly re-established my Ghost Girl reputation in middle school. I hadn’t seen a ghost in a while, which was distressing—I was worried I’d lost my power—but I thought about them all the time. I wanted to seek them out, so I decided my career goal was to be a paranormal investigator. For a school project, I presented an enormous research report on the supernatural—intelligent hauntings, residual hauntings, ghost photos, orbs, wisps, spiritualism of the late 1800s, infamous debunkings—and explained my professional aspirations to bemused classmates. I carried around a camera, hoping to glimpse unearthly beings in my photos.

Among the kids, I was popular. I didn’t fit in anywhere exactly, which allowed me to sort of fit in everywhere. I floated between the popular kids, was the only student staffed at both the school paper and yearbook, hung out with a group of mostly skaters outside of school, and had a permanent seat at the alt-kid lunch table, where corpse-painted goths, spikey punks, furries, scene kids, and fluorescent ravers coalesced at the only outdoor picnic bench.

In each group, I was the weird one. I was accepted, but still felt like an outsider. I wasn’t white, for starters. I didn’t look like the other kids. But I dressed like them. My goth style was still unrealized; I couldn’t buy my own clothes, so I dressed in whatever Mom bought, and she bought what the other kids had, so I wore high Y2k tween style: hoop earrings, miniskirts, tiny necklaces adorned with silver bows. Besides, you couldn’t quite go full goth anymore, because even in the alt world it wasn’t quite cool. The skater boys wouldn’t go for it—a key consideration for me. I looked like everyone else, but talked nonstop about my macabre interests, which they all thought were cute.

They didn’t understand how deep it ran. I became obsessed with death, the grotesque, black magic rituals, and cults. I scoured the Internet for tattoos I’d get someday, and shoplifted books about serial killers. I’d visit websites with infinite scrolls of crime scene photos, or step-by-step instructions on how to conjure—or exorcize—demons. I got my hands on a Ouija board so I could communicate with the dead. In particular, I wanted to talk to River Phoenix, my dearly departed crush, for whom I had built a shrine in my bedroom.

*

Growing up with a theologian for a grandpa presented challenges. I believed in ghosts, but I couldn’t wrap my brain around a man in the sky demanding to be worshiped. Even for me, a believer in leprechauns, the concept of God felt so silly.

One night three months later, I felt a hug from above and an affectionate whisper, “I love you, sweetie.” It was indisputably Grandpa’s voice.

When my grandfather got sick, that spiritual confusion turned to anger. My grandfather was my first real father, the man who raised me and showed me that men could be kind and good-hearted, and here he was in a hospital bed, fading away, his eyes receding into their sockets, his body wilted to half its size. Meanwhile, my actual father was free to roam the earth, tormenting women and children for fun.

I will never understand how a presence so big could be taken so quickly. Grandpa was the adhesive that held our family together, the central dependable force. He was a farmer, a carpenter, a musician, a theologian, a doctor of psychology, and an ordained Lutheran minister. And then one night, Mom brought me and Simon into the family room to tell us he was gone.

At my grandfather’s funeral, I tried to hold it together. Images of us flashed through my mind: the sound of his voice reading bedtime stories, and scripture; eating strawberry ice cream holding hands; his hands full of tadpoles in the farm’s stream; his honking sneeze, and the hanky in his back pocket; the sound of his piano echoing through the house.

After the funeral, I told Mom I didn’t believe in God. She said, “Well, then you can’t believe in ghosts either.” A conundrum. Maybe so, I thought.

One night three months later, I felt a hug from above and an affectionate whisper, “I love you, sweetie.” It was indisputably Grandpa’s voice. I was wide awake, laying in bed listening to music. The moment the words entered my ears and I felt him, he was gone. Startled but unafraid, I lay almost paralyzed by surprise, then ran to wake up my parents, who sleepily shared in my delight. It felt like a kindness from beyond the grave and a reminder that maybe my powers hadn’t disappeared—but for the first time ever, I doubted myself. Wrecked with grief, I lacked my previous confidence as Ghost Girl. I flirted with nihilism. Maybe there’s nothing to believe in. With my grandfather gone, I thought, it was easy to think that we’re all just alone.

That’s when the sleep paralysis started.

7.

It happened every night as I was falling asleep: I couldn’t move. I’d try to wiggle a toe, any toe, move a finger, try to break free. But I was trapped. My eyes were closed but I could see the room and myself, as if viewing my own body. I’d see the bed levitate. I’d hear someone whispering: Helen. Shadows danced around me in the darkness, claws gripped my comforter and yanked it from me. I’d see myself escape the clutches of these claws, gasping for breath, checking my pulse to make sure I wasn’t dead. Gathering my comforter back around me, I’d lay in the dark, praying it would cease. But it would go on like this, until my body collapsed from exhaustion. I’d wake up shocked that I’d slept at all.

“I think I need an exorcism,” I told Mom one morning. She was amused. I was serious.

Sleep terror is a physiological phenomenon, and always harrowing, but mine was chronic and hallucinatory. It felt paranormal. I rarely slept. I saw people hanging from the ceiling fan, mutilated bodies on the floor. I told my parents—by now, Tom was easing into “Dad,” and they were together becoming my “parents”—and they took me to a series of baffled doctors.

I was so afraid of going to sleep I’d try to stay up all night on the phone with friends, like the kids in Nightmare on Elm Street. The doctors evaluated me for conditions like schizophrenia and narcolepsy, all negative. I was prescribed antidepressants, benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and muscle relaxers. Nothing worked.

The doctors either believed I had some mystery disorder immune to medication or thought I was making it up for attention, something they’d hint at once Mom left the exam room. I read later that the reason victims of sleep paralysis see shadow people, hear screams, and feel pain is the flood of serotonin, which creates hallucinations by activating panic in the brain. But I figured I was possessed. Maybe it was all my dabbling with spells or the time I spent browsing demon conjuring tutorials in online paranormal forums.

“I think I need an exorcism,” I told Mom one morning. She was amused. I was serious. For a year, I’d repeat Hail Marys to myself in the dark. We weren’t catholic, but I’d read that demons were afraid of Hail Marys. The prayers never worked. If God was real, he wasn’t listening. More proof.

8.

My parents were at the top of the stairs, discussing something serious. Simon and I quietly listened, always wondering if we were in danger. My parents believed someone was trying to find us and were considering hiring a private investigator. Even after moving across the country, and then several times more, the fear followed us.

By now, Simon had his driver’s license, and when he drove us to school, he was always looking in the rearview window, suspicious that we were being followed. Every car that got too close must be tailing us. Simon drove as if in evasive maneuvers. When he ran a red light accidentally, it felt strangely exciting, like we were bank robbers.

I was now a teenager, and embracing my full fashion destiny: a mullet of black, box-dyed hair with streaks of pink and purple, a Trainspotting t-shirt, Union Jack Doc Martens, FCUK skinny jeans I’d bought overseas. As with many teenage aesthetics, mine was composed of various finely graded sub-specialties: ’77 punk, post-punk, hardcore, with a touch of scene. Even still, I couldn’t shake the preppies. In my junior year, my outré style got me voted Best Dressed Senior. I remained popular.

“He probably hired someone to find us,” Simon said. I thought of my father marauding out there, hunting methodically, closing in.

I rebelled. I detested authority, turning into a smartass who harassed teachers, stole and destroyed school property with abandon, and spent a lot of time in ISS. I developed a new persona as a boy-crazy shock jock with abrasive style and a vulgar personality. It drove Mom crazy.

*

The envelope came in the mail, addressed to Simon. Inside was a check, signed by the same hand, for $1,000. “For your birthday,” the card read. He’d found us.

It had been years. The shadow fell over us again. As we’d feared. Maybe it was inevitable. “It means he has our address,” Mom said. At first, my teenage instinct was glib. “Just cash it!” I said. “Free money!” Simon giggled. I mean, neither of us had ever seen that amount of money before. “No!” Mom hissed. “If you accept anything from someone like him, you will never, ever be free.”

Simon tore up the check.

Simon and I were less than a year apart, but we were not close. Once we outgrew our Beanie Babies, and playing video games together, we rarely spoke. At school, we were grouped together as the “kidnapped children,” and we resented it. We knew things about each other we couldn’t speak of, and the result was that we never talked at all. But now our father had reared his head. We were reunited in our fear and hatred of him.

“He probably hired someone to find us,” Simon said. I thought of my father marauding out there, hunting methodically, closing in. After the check showed up, my parents got a new alarm system, bought more guns, and alerted the police. When Simon would drive us to school, we were both skittish, turning our heads at any sounds, and talking about what we’d do if our car was suddenly boxed in by a Bogeyman ambush. Would he shoot us? Seemed unlikely. Would he try to abduct us again? We were too big. “One thing’s for sure,” Simon said. “It would be a really stupid reason to drive all the way to Texas.”

*

A few weeks later, I was on MySpace, seeking out fellow serial killer enthusiasts and coveting the tattoos of Suicide Girls with long, racoon-tailed hair whose profiles were full of animated flames and skulls, when there was a surprise message in my inbox. “Dear Helen, my beautiful child,” it began. My heart sank. I tried not to read it, as if the words were a dark spell to avoid. It was long. The sender’s name was Naseem Z.

We eavesdropped on more consternation from my parents at the top of the stairs. Whispers about lawyers, more courtroom appearances.

No longer confined to my parents’ computer room for online exploits, Simon and I both had our own desktops, situated across from each other. Simon was behind me, puppeteering a Level 70 Paladin in World of Warcraft, his chief interest in life. I flicked the back of his skull. “I can’t talk,” he said. “Check MySpace,” I said. It was an odd request. We weren’t even friends on MySpace. He paused WoW, and logged in, and there it was, a message from Naseem Z. to “my beautiful child.” Simon froze. “Don’t tell Mom and Dad,” Simon said. “Just delete it.”

This was typical in our family, where we were taught to cope with feelings on our own, even the everlasting dread of our father. Maybe this was meant as protection, to act like that was all in the past in the hopes that it was. But it wasn’t. Emotionally, I was left to my own devices, which were my aesthetic armor, ghoulish obsessions, and sarcastic wit. But these were defense mechanisms, not therapy. And it felt like a shocking incursion, a deep strike at our hearts, to find his name there, in our inboxes, in our computers, in our bedrooms, alongside our adolescent explorations and chatter with friends. We deleted the messages without reading them and hoped that would be the end of it.

There were no new messages on MySpace, but some time later, my parents received a summons. “He’s suing them for ‘hiding us,’” Simon explained, incredulous. “As if they are blocking him from knowing us.” We eavesdropped on more consternation from my parents at the top of the stairs. Whispers about lawyers, more courtroom appearances. Would we ever be rid of him? One day, at dinner, Mom handed Simon and I each a document.

“What is this?” I asked.

“It says we are not hiding you from your father. It says that you don’t want to see him.”

“Is this because of the lawsuit?”

“Yes,” she said. “It’s a testimony to the court. Read it and sign if you agree.”

We didn’t need to read it. Simon started rummaging through the junk drawer for a pen. I held the document. There had already been many proceedings, custody awards, successful adjudications in Mom’s legal battles with him. But that was in her name and these documents were meant to be our own testaments, our first opportunity to put up a fight ourselves.

Not long before this, I’d found a folded piece of paper in an old recipe collection Grandma sent Mom. It was a family tree, dated back to the 19th century, and the first name I recognized on it was my great grandmother’s: Helen Vogelsong. I’d always thought that this was also my name. But what I saw instead was Simon and Helen Z., Children of Laura and Naseem. My stomach dropped at the strange discovery.

Growing up, I had loved calling myself Helen Vogelsong the Second—the fanciful sound of it, the delightful generational echo—but there, on the yellowing paper, was my real birthname, and within that name was inscribed the horror of our lives in black and white. Now, I was holding a new document. And my own pen. I could correct the error in that old family tree. Around the dinner table was my new family, Simon and me, the children of Laura and Tom, whose legal name I’d been given years before. “I’m sorry,” Mom said, looking at us with a distress that implied she always would be. There was nothing to be sorry for.

Simon handed me the pen, and I signed: HELEN DONAHUE.

9.

I was 22 and had finally transformed completely into the girl I’d seen in the graveyard all those years ago, down to the leather o-ring choker. The latest ink scrawl on my ribcage read Fuck Forever. There had been no word from Mr. Z. for years, not since he’d sued my parents back in 2006.

Until he found my Facebook and saw my appearance: the tattoos, the black hair, that choker strapped around my neck like a dog collar. “You have let our daughter become a whore,” he wrote in a vicious letter to Mom. He attacked her for letting me run around Brooklyn covered in tattoos: “How could you let this happen?” He said I would burn in hell, compared my life to the perversions that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah.

Now we could talk about it, three generations of women all protected by the same ghost.

At first, his reappearance after a half decade sent me into a tailspin: What if he has my address and shows up? After all, I was on my own. My parents couldn’t protect me every day; Simon couldn’t sweep my apartment for bogeymen. But the vitriol in that letter was in fact the last time we heard from my father directly. He was apparently so repelled he never contacted me again. Ironically, the tattoos I wore like armor fulfilled their purpose. They scared off the Bogeyman for good.

*

That Christmas, at a family reunion, I told my grandmother how after Grandpa died, I used to poke around the Pennsylvania farm house, hoping to sneak up on his spirit playing piano or chopping wood. Whenever we talked about Grandpa, she listened like she was hearing a sermon. “He visited me once,” she said, her hands gently folded. “I wanted to go with him, desperately. But he wouldn’t let me.” I told her I had never found Grandpa at the farm, but he had come to me once in my bedroom. It was a few months after he died. Grandma got misty-eyed. “He was your first father,” she said. “I know,” I said. And then I was crying. “There’s no guidebook for how to raise kidnapped kids.”

Mom had also encountered Grandpa, in her case in a dream. I was 15, and he told her that I would experience several years of suffering—which I did —but that I would be ok. And now we could talk about it, three generations of women all protected by the same ghost.

On a trip back to Pennsylvania, Simon and I visited our old houses. We drove Grandma’s car to our first house, the one across from the jail, the one where our mother locked up every night against the Bogeyman and Thomas came out in the rain. We checked out the cemetery where we used to take walks. I imagined the scene narrated by David Attenborough: see the adult siblings as they now walk across the graves they once pirouetted over with abandon. Children no longer, they are forced at this moment to reconcile with their traumatic past. I couldn’t believe we used to live here.

We went to the Victorian house, where on the porch there was a multi-colored chalk sign in child-like chicken scratch that said: STAY HOME! STAY SAFE! The paint was chipped; the pond we’d dug as kids was filled in. The yard was overrun with weeds. Easter decorations adorned the door. It was autumn. Here I was, visiting the house as an old friend… In the end, it turned out OK to be old friends.

I had done some research and discovered that the Victorian was once called the Hayes-Hicks House. It was purchased in 1875 by a prominent Irish doctor who lived and worked there. He had written a book, a medical reference he used in his downstairs practice. Simon and I figured this must have been the book our ghostly gentleman was asking for. Where’s the book?

The gingerbread trim was gone from the dormers. I peered inside. I could see doilies, antiques, and ceramics, the kind elderly people collect. We knocked. No one, dead or alive, was home.

*

The last thing any of us heard about my father was in 2016, when I got a frantic message from a woman on Facebook. She wanted to know why Mom had left my father. She’d been told he was rejected because he was Iranian, that we had mistreated him. She said she had less than 12 hours to get the truth: he was in jail overnight for beating up her teenage daughter and would be released in the morning. Wary of any contact relating to my father, I asked her for proof. She sent over the police records from earlier that day. She also said he’d been threatening to kidnap their two children: two twin boys, not much older than Simon and I when we were taken. I told her the truth. I told her to run.

I realized then why we hadn’t heard from Mr. Z in years. The Bogeyman had moved on to another family. He was haunting someone else.

I used to wonder about the nature of ghosts—spiritual remnant or self-deception?—now I think more about the nature of ghost stories. Whether the supernatural is real or not, ghost stories have always been with us. They clearly serve a purpose. Ghosts float through folklore, and rattle chains throughout literature. There are spirits in the bible, Torah, and Quran. From Gilgamesh to Goosebumps, ghosts make their appearances. Sometimes they carry a message. Sometimes they are the message. But the ghost story is always meant to tell us something about ourselves.

These stories have many tropes. Mine starts with one: troubled family moves into new house which turns out to be full of ghosts. That usually means the family, terrorized, either fights the evil forces, or flees, led by the heroic patriarch. But for me, the ghosts were a comfort, and the evil was my father.

Everyone has a ghost story of some kind. Real or metaphorical. If you’re not haunted by ghosts, you’re haunted by lost family, lost love, broken friendships, tragedy, disaster, regret. For me, it’s all of the above. In my ghost story, the material world was the scene of my dread, and the paranormal world offered protection. I learned that the Bogeyman is real. And yet, I survived.

Who are your ghosts?

You are someone’s ghost too, you know.

Boo.

_____________________________

This essay was originally commissioned by Epic Magazine; with editing contributions from Joshuah Bearman and Gina Mei.

Helen Vogelsong-Donahue

Helen Donohue is a writer and ceramicist based in Los Angeles. She’s held columns at Vice and Playboy, and has written op-eds, features, and profiles for publications like Art in America, Billboard, Notion Magazine, InStyle, Cultural Fan Fiction, Inverse, Breakdown Mag, The Conversationalist, Quartz, and BBC America.