1983

Audrey McGuigan is in front of the wire fence that marks the end of their garden, where newly planted lawn gives way to tufts of roseroot and marram grass. Behind her, Ben Bulben is under cloud, only the west side visible, curving into the sea. The tide is out, an acrid slime covering the seabed. A dog has left the carcass of a sewage-fattened mullet in the low dunes and the smell repulses her; she is seven months pregnant. Marty hasn’t figured out how to use his new camera, and Audrey has been stock-still for five minutes. He’s just noticed how huge she is, at least as big as when she was at full term with Rory, who is out of the picture, climbing over the Gibraltar Rocks to get away from his parents’ bickering. After a clutch of car sales, Marty goes to auctions. He has bought a scrap of waste ground, a terraced house on Harmony Hill, a derelict shop near the docks. He also bought the field that borders Gibraltar. Half an hour ago, he put a sign on one of the gates that reads keep off these lands. Where is he going with his lands, Audrey wanted to know, and him reared in Belubah bloody Terrace. Their Queen Anne–style house is a bespoke pine kitchen away from finished. Rockview Lodge, they’ll call it; there will be a row about that too.

1990

This one was taken by a photographer. The parish priest is between Marty and Audrey, delighted to pose with the man who gave him 5 percent off a new Mondeo and threw in alloy wheels for nothing. Audrey’s mouth is smiling. Her left hand is buried in the cloud of Shona’s veil to stop it from blowing away. The Communion dress is cut from Audrey’s wedding gown. Shona would have preferred a dress from a shop, but her mother had been so keen to take scissors to the lace and tulle she hadn’t said so. Her palms are touching, as if in prayer, a white satin handbag swinging from her wrist that’s already bulging with cards and cash and Nanny Lynch’s rosary beads. The more you have the more you get, Marty thinks. The day of his own Communion his father poured him a whiskey in the scullery and went out to the pub to celebrate by himself. There’s a meal booked in the hotel, where he’ll have to buy drinks for everyone in the bar, because that’s what is expected when you own half the town and employ the other half. At least it’ll give him something to do while Audrey and the children are at the long table, flanked by the Lynches. Rory is in a brown blouson jacket, his right foot raised an inch off the ground, as if he’s about to bolt. Audrey would bolt too, given half a chance.

2001

Shona is wearing a one-shouldered purple dress, her long hair straightened, eyebrows thin and arched. She is smiling over at her mother while Marty takes the picture. The boy beside her is called Keith and has a blond ponytail and a bar through his eyebrow. His handshake is limp and Marty thinks Shona should think more of herself and find someone else. Not that he will say so. He and Shona aren’t that close. Keith has been making a particular contribution to Shona’s low self-esteem. A couple of shoves, what the counselor will later call verbal abuse, and the previous night a smack that cut through the fug of hash in her bedroom.

2011

The florist has erected a bower of pink peonies and unripe wheat and white rhododendrons at the end of the garden, on the exact spot where Marty photographed Audrey with Shona in her belly. The family are in front of it, Marty and Audrey on either side of the bride and groom, Rory and the English girl he lives with in New Zealand (South Island, as far away from Rockview as you can get) beside Audrey, yet slightly apart. Shona’s hair is set in loose waves. She has just married Lorcan, an eejity fella, in Marty’s opinion, but an improvement on that weasel Keith. They have been blessed with the weather. Not that it matters, because there’s thirty grand’s worth of a marquee with a merbau floor and chandeliers and vintage china teapots filled with cornflowers and anemones. Audrey is wearing oyster-colored georgette. Her wig is a toffee shade that almost suits her, although it feels like a bathing hat she had as a child, a pink rubber abomination with flaccid flowers. Marty is preoccupied. He’s not a man for speeches. He’ll talk about how beautiful Shona looks. He’ll say how happy he is to welcome Lorcan to the family, that he had better be good to Shona or he’ll have him to answer to, and everyone will laugh. (He isn’t joking on this front, as Keith with the bar in his eyebrow would attest.) The rest he’ll keep to himself. That he would not have believed you could love a child that wasn’t yours until Shona’s arms were reaching up at him, demanding to be carried. How hard it was to give the love in the first place. How very much harder not to give it.

1980

Audrey’s hair is cut in a pageboy style, her fringe full and bouncy. She is wearing a light blouse with shoulder pads, and a Black Watch kilt over leather boots. There’s a pair of scissors in her hand. The tape she has just cut hasn’t yet touched the ground and looks as though it’s swirling about her, like the ribbons gymnasts dance with. Behind them are two brand-new Ford Sierras, all curvy windows and bubbly lines. They will be recalled in a few months because of a fault with the carburetor, and Marty will almost lose the business for the first time. His suit is loose at the waist, the creases in his trousers sharp.

The photograph was a centerfold in the local paper, other businesses placing an advert around it to congratulate them on the new showroom. The one on the bottom right is for the legal practice where Audrey works part time. “Wishing Audrey and Marty all the very best,” it read, the Mullen & Kilcoyne logo bent over a drawing of the scales of justice.

1983

Treasa Callaghan is holding the camera and has already appointed herself godmother.

Audrey is propped against pillows holding Shona Bridget McGuigan, who arrived at 11:04 a.m. while Marty was in the Innisfree Cafeteria beside the hospital chapel, moving pieces of currant scone around a plate. Shona is a fine child, nine pounds four ounces. A remarkable weight for a baby who arrived five weeks early. Bridie Lynch has swung one ample bum cheek onto the bed and is regarding the pair suspiciously. She may have left school at fourteen, but she knows when her daughter is trying to hide something. Audrey is watching Marty, who is out of the frame. He’s sitting on the windowsill, looking down over the town. To the west the sky is almost black, a cold blue to the east. Three watery rainbows are arching over the town, over the fairy fort in front of his mother’s council house, over the crow’s nest on the old Polloxfen building, over the mock-Gothic tower of the courthouse. Unless you counted the night of the Chamber of Commerce Annual General Meeting, he hasn’t been near Audrey in over a year, and even then he hardly put a hand on her. He had come in quietly and sat up against the headboard until an antacid tablet started to work on the reflux caused by his hiatus hernia. She had climbed onto him without a word and by some trick of her thumb and finger taken him in, rocking in his lap until he filled her. It was like having sex with someone else. Not that he has ever had sex with anyone else. Audrey wishes they’d all just go, so she can figure out where the pay phone is and try calling Matt Kilcoyne again.

1976

There’s a heat wave. A wedding car is parked to the right of the cathedral. The rear passenger door is open and Audrey is waiting, fishtail train spread across the melting tarmac, lace almost blue in the implausible sunlight. Treasa Callaghan is meant to be holding the train, but the head bridesmaid is eleven feet away, up on her toes, her mouth to Marty’s ear. Marty is looking at the wedding car. Treasa Callaghan has just told him Audrey is wearing a baby-blue garter under her dress. Later in the hotel in Westport, when he puts his trembling hand up her satin nightgown, he’ll feel a ruched rash on Audrey’s thigh, where the elastic has eaten into her skin in the heat. She’ll flinch, but he’ll be so nervous about finding the right hole he won’t ask if she’s all right or think about the garter again until forty years later when he sees this photograph.

1986

In homage to Jungle Book, Shona is naked except for a fat nappy and a banana skin that is opened on her bobbed hair. She is lying across Marty’s chest, her cheek against his. Marty knows the exact date on which this photograph was taken. June 22, 1986, the Sunday of the Connaught final. Galway beat Roscommon 1–8 to 1–5. He missed the first half to let Shona finish watching her video; Shona is a daddy’s girl. Only three people know Marty isn’t her daddy. He is fairly confident about that, because he called out to Matt Kilcoyne’s house in the Lower Rosses the day Shona was born. It didn’t take much to warn him off, which had annoyed Marty; the wee rat could at least have fought for them. On the way back up to the hospital, though, he fretted briefly that he might have just kicked Matt Kilcoyne’s bollocks into his mouth.

The photograph is an instant Polaroid. Audrey takes it and waves it in the air, watching them, watching her child pressing against a man who isn’t her father, trying to mesmerize him with a rendition of “Trust in Me.” Audrey gave up her job in Mullen & Kilcoyne Solicitors after Shona was born. She was only working to get her out of the house, she told anyone who asked. Matt Kilcoyne Bachelor of Law is engaged to a twenty-four-year-old emergency nurse from Longford. It has been almost three years, yet some days the loss of him weighs so heavy on her she can scarcely breathe.

2016

Audrey is holding up a glass of champagne. Her navy cashmere cardigan is flattering to the jaundiced tint of her skin, the white hair that has begun to fur her scalp since they stopped her treatment. Shona says she looks like Jamie Lee Curtis, who Marty has never heard of. Lorcan is holding Amber Mae, who is two, dark-haired and earnest like her mother. Shona looks tired, her pregnant belly only a little fuller than her mother’s distended abdomen. Marty is beside Audrey, his arm stretched out behind her, close but not touching. Rory left for New Zealand three days ago. He has split up from the English girl, who won’t give him access to their son.

This photo is Shona’s favorite. She is going to put it in the Mass leaflet. She wants the funeral to be a celebration of her mother’s life. Shona has planned a party for afterward, a buffet with tables in the garden and large prints of family photos around the house. Marty would settle for a meal in the hotel, but doesn’t say so. The last few years at Rockview have been almost happy. Like visiting some other couple, Shona has told Lorcan. They’ll send Audrey off from here.

1973

Audrey is behind her mother, on a slab of rock. She is wearing a white halter-neck dress and has tied a navy-and-white-striped scarf around her hair. She is holding sunglasses in her right hand and looking at the camera. Not smiling, just looking. Marty is out of the frame to the right. He goes to Gibraltar at high tide twice a week to bathe in the tidal pool the council constructed in 1951; the houses on his street were built without bathrooms. He has taken off his shirt and is aware of the ruddy skin that rings his neck and forearms, the startling pale of his torso. He is close enough to see that Audrey has a black bubbly mole just under her left shoulder blade, raised and horny, like a wood louse. He wonders what would happen if he ran his finger across it, if it would yield to his touch or stay raised. The color in the photo has both faded and brightened to give everything a tint you never saw then or since. Marty can confirm that the mole stayed hard when you pressed it, though. And that, in the early days, Audrey Lynch had quite liked the feel of his fingers on her back.

__________________________________

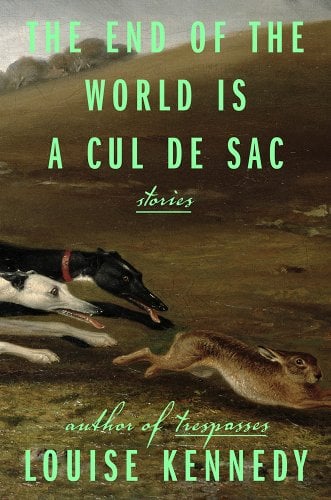

From The End of the World Is a Cul de Sac by Louise Kennedy, published by Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Louise Kennedy