Ghostly Taboos: Superstitious Rules and Gendered Restrictions

How Researching the Forbidden Shaped The Themes of My Novel

When researching a setting, one of the best ways for a fiction writer to understand the cultural mores of a time and place is to research taboos. This is especially true of ghostly taboos, whose threats about crossing boundaries derive from communal judgement rooted in assumptions about gender, politeness, morality, and the body.

Historically, taboo was related to superstition and religion. Terror associated with taboo behavior kept people in line, especially women, children, and the poor. Common historically taboo behavior included walking under ladders, allowing a black cat to cross one’s path, and spilling salt. These behaviors related to fears about safety, resources, and gender and were connected to the personal identity of the individual in society.

For instance, long ago salt was very expensive, so spilling salt was taboo to the point that if one spilt salt even on accident, one had to seek protection or forgiveness, especially if poor. Ladders were dangerous to walk under, so making them a symbol of the gallows reminded people how deathly walking under a ladder could be. Black cats were a reminder of witches, so it was taboo (or bad luck) to see a black cat, especially for women. As witches’ “familiars,” black cats were a frightening reminder that witches were everywhere. Even more terrifying, black cats were a reminder that anyone, especially women, could be accused of being a witch. In times when society watched women with an eye toward any behavior that might mark them as possible witches, a black cat was a reminder that a woman had to be careful of how she was perceived. The taboo of the black cat reminded women: don’t be seen by a witch and don’t be seen as a witch.

When writing contemporary fiction, the question of taboo becomes even more complex; although most contemporary readers don’t believe that taboo behaviors might be punished by a supernatural force, they are still fearful of taboo behavior, which is often code for gendered behavior (such as a woman exposing her body in public). On the surface, taboo often appears illogical or nonsensical. Beneath the surface, it is sinister. It is the cultural nerve of psychological fiction, a deep dive toward the heart of character identity, and a way for writers to reveal truths about society.

What punishment does the violation of taboo risk, and how does the invisible hand enforce society’s taboos? And who benefits?

Today, taboo no longer typically takes the form of the supernatural. Instead, it appears as retribution from the invisible hand of society through shunning, excommunication, rejection, and judgmental labeling, keeping behavior and identity in check. In all societies, there are the “good people” and the “bad people,” the good side of the tracks and the bad side of the tracks, the safe and the unsafe, the good girl and the bad girl, the clean and the unclean, the virgin and the whore. These dichotomies are connected to taboo.

For a writer, revealing and researching taboo is akin to a narrative deep dive on behavioral psychology in a particular setting. Analyzing taboo, in addition to providing a sort of forensic accounting of a character’s fears, gives context for deep characterization because taboo has always been about control: controlling the self and the individual being controlled by society. A writer who understands this tension can use it as subtext to build on two classic categories of conflict: character vs. society and character vs. self.

One of the ways for a writer to uncover themes related to deep characterization is to ask: What are the unspoken rules society imposes upon its people? Which people do these unspoken rules apply to and in what circumstances? What punishment does the violation of taboo risk, and how does the invisible hand enforce society’s taboos? And who benefits from a society’s ideas about taboo? The invisible hand of societal judgment always affects our relationships to others, creating boundaries between acceptance and ostracism.

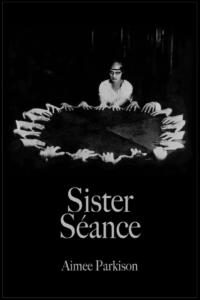

In writing my historical novel, Sister Séance, I researched taboo topics of the Civil War Era. My research, funded by an American Antiquarian Creative Artist Fellowship, included the study of historical newspapers, illustrations, and diaries. I encountered gendered taboos such as women who engaged in public speaking, women who remained unwed, women who grew pregnant out of wedlock, women who enjoyed sex, and women who engaged in interracial romance, especially in the case of a white woman and a male slave.

In general, women who transgressed by having sex outside of marriage, or enjoying sex, were seen as “fallen women.” Any role that wasn’t submissive, motherly, or virginal was questioned by society. Even public speaking for women was taboo. Women who engaged in public speaking were labeled “sluts.” There were few career pathways for women desiring authority, until Spiritualism opened a pathway to free women from gendered taboos through séance.

Séance negotiated gendered taboos by allowing women to speak publicly in the voices of dead men and by allowing unwed women to “birth” celebrated materializations. These materializations were thought to be spirits in physical form, though my research exposed unsafe ways that female mediums used their bodies to hide and “birth” materializations, including mediums inserting photographs or cotton “ectoplasm” in noses and other orifices.

Taboo is at the heart of communities and their social hierarchies.

However, women who transgressed gender taboos outside of Spiritualism were not so lucky, since they didn’t have the spirits to excuse their transgressions. For instance, the taboo of interracial sex, slavery, and pregnancy between a white woman and a Black man was so intense that one of my characters, Viv Hayden, attempts to hide her pregnancy to protect herself from becoming a “fallen woman.” As Viv’s character changes through taboo-driven conflict, her former identity is taken over by a new identity, the fallen women or dreaded other, and her former identity becomes ghostly.

As in the case of Viv, any character’s fear of taboo is a way to preserve the self, to protect the self from becoming the dreaded other. Each character has more than one self when it comes to taboo—the current self and the ghostly self that threatens to take over if the character transgresses into taboo.

As subtext, taboos generate tension in characters’ lives and complex motivations in what must remain forbidden or unspoken. Sociologically, avoiding taboos is about protecting the individual from society’s judgment. Psychologically, the avoidance of taboos is less about protecting the self from the other than about protecting the self from becoming the other.

*

To create and know a character, a writer must know and create the character’s world. Whether that world is contemporary or historical, real or irreal, taboo is at the heart of communities and their social hierarchies, and locating taboo requires research into the forbidden in a story’s world. For characters wealthy or powerful enough to be lured by the seduction of transgression without fear of consequences, taboo becomes haloed with desire. Repressed sexuality creates the desire for forbidden sex. Laws against drug use create illegal drug trade just as prohibition creates speakeasies. Those with privilege are most able and willing to transgress taboo for pleasure and novelty of experience while rarely paying the price, because the invisible hand only touches certain characters in certain ways (depending on the setting and context).

My historical research led me to understand that in times of war during the time period of my novel, death taboos affected people of all genders, races, and ages with a morbid desire to approach the grave. This was especially true in the Civil War since the Victorian American society had a notion of good death vs. bad death. Bad death was taboo but often unavoidable for families, especially because so many men fought in the war and died bad deaths, suffering far from home on battlefields, their bodies unrecovered while so many children died of disease and so many women died in agony in childbirth away from their solider husbands. A good death—at peace, painless, and at home with loved ones—was much desired, as opposed to a bad death of suffering.

In researching Sister Séance and building its world, I discovered that working as a medium allowed women to free grieving mourners of death taboos by speaking publicly in the voices of dead men, dead women, and dead children. Mediumship was a job where a woman could be respected, in charge, and be her own boss while providing hope and relief. The writing process taught me that researching the forbidden could shine a light on my characters’ world, whenever the ghostly construction of identity was threatened by taboo.

My novel became about saying goodbye when guilt and grief wouldn’t let go. Spiritualism became a pathway, allowing communication with the dead, helping to overcome the taboo of bad death. It allowed loved ones to say goodbye to soldiers who died away from home in battlegrounds or hospitals, and it allowed grieving mothers to communicate with dead children in a time when some women were so sick with grief that they wanted to dig bodies from graves to say goodbye.

___________________________________________________

Aimee Parkison’s SISTER SÉANCE will be available from Kernpunkt Press on October 31st, 2021.

Aimee Parkison

Aimee Parkison’s collection of stories about girls in confinement, Girl Zoo, was published by FC2 and co-authored by Carol Guess. Her other books of fiction are Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman, Woman with Dark Horses, The Innocent Party, and The Petals of Your Eyes. She teaches in the creative writing program at Oklahoma State University. More information about Parkison and her writing can be found at www.aimeeparkison.com