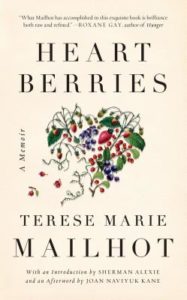

Getting Through School Let Me Talk About Pain

Terese Marie Mailhot on Motherhood, Ghosts, and Inherited Sorrow

My education was a renaissance, and I know what comes after discovery. I graduated in a woven cedar cap and blue shawl. I was given a sovereign land to write every transgression.

When I walked across the stage, I remembered, some years ago, when Isaiah had lice. Doctors couldn’t see the nits and told me I was just imagining things. I put two rooted teardrop eggs that were attached to my son’s hair into a sandwich bag. The nurses looked at it closely and told me it could be nothing.

Only when I started to pick his scalp with my fingers, on the plane to America, did people seem to care or see. The entire flight, my hands worked and found each clinging thing. Isaiah was happy to be still, and happy to have my fingers acknowledge each exposed space—his follicles too. Every child deserves a type of servitude. He fell asleep and dreamed. I know because he salivated and murmured against my chest. When every tiny seed and itch was stripped, we landed, and he woke up.

I remember how well my work on his head was timed, and that America would be the beginning of our new life. I remember being ashamed to have groomed my baby like an animal on a flight filled with white people. I remember that motherhood is mostly bearing shame to dress my children, to feed them, and to spare them the things I wasn’t spared.

I came to America because I lost my baby and had one in my care—to feed. I came because I didn’t have my GED. I came because I was done with ghosts. It was all too ugly to say, until I received an education and walked across the stage.

Sherman Alexie read my work and said, “It’s no wonder that this narrator is crazy. She’s Indian, and she’s smart. Who could survive that?”

*

If the Institute of American Indian Arts was a renaissance, then this is what comes after discovery.

I became an editor. They pay me for my work. I became a fellow. Words I never knew to be—I am.

More than a drunken father or monster, and more than the bright of my iris, or the hope I was given from my grandmother. I’ve exceeded every hope I gave to myself.

I still hold my coffee, and remember until it runs cold.

When I hear empty bottles, I remember. Empties are a cliché—the sound of them is so familiar. The collective sound of glass against glass, muffled by brown paper bags and collapsing tin. Empties are my father and Larry.

Sometimes I hide my empties because I don’t want to be a drunk Indian. I do get drunk, and I am Indian, but not both.

My mother took pictures of my father when he was passed out drunk to remind him that he was a drunk. Those pictures, at a time, were all I had of him.

I wonder if he ever felt this ugly, trying to exact the truth of me. A little ghost he lost. I hear empties, and I hear him. I learned to hide my bottles like him and sometimes take from the world like him. I don’t think he was wrong for demanding love—it was the manner in which he asked, and whom he asked that was unforgivable.

“I didn’t expect the best things, and I have turned loss into a fortune—a personal pleasure. It’s not a sustainable joy, I know.”

It’s strange that his ghost won’t abandon me. It is the type of strange that compels me to take each bottle from my trash and consider the volume of my stomach. I want to consider what I poured into myself and how my father made a life of not remembering. I know the limit of what I can contain in each day. Each child, woman, and man should know a limit of containment. Nobody should be asked to hold more.

*

When I walked across the stage, I thought of you.

I believe you want my sorrow, and now that it is more sophisticated, it’s less contrite—less of a beggar. I’m less of a squaw. I can’t entreat as well.

This story is yours, culprit of my pain. Which one of us is asking for mercy?

What do you even want with my sorrow? You are so inefficient with pain—I realized you never had to cultivate it the way I did. The way Indian women do.

You think weakness is a problem. I want to be torn apart by everything.

My people cultivated pain. In the way that god cultivated his garden with the foresight that he could not contain or protect the life within it. Humanity was born out of pain.

I learned how to abstain from good things. I didn’t expect the best things, and I have turned loss into a fortune—a personal pleasure. It’s not a sustainable joy, I know. I’ve seen you happy. Being close to your joy has been a measured success. I’ve somehow retained myself, after all of this with you—retained the ability to revel in loss. This loss has spun and twisted itself into silk my sons will hold to their faces.

I almost killed myself, trying to match your potential joy. It was taking my misery. The thing I am most familiar with. The thing I rove into love. I realized that I could have you and the pain.

Pain expanded my heart. Pain brought me to you, and our children have blood memories of sorrow and your joy, too. They inherited their share, to cultivate their own children, whose humanity and gentleness will remind them of you and me.

Our boys, their compassion to will away inherited sorrow, it’s what makes them good and mine and Indian. Had I not been born and cultivated in this history, I wonder how dim and dumb my life would be. I feel fortunate with this education, and all these horrors, and you.

*

Today, in front of a slew of white authors, during a fellowship, with a drink in my hand, I said that I was untouchable. There was a gasp, and maybe it was a hundred years of work for my name to arrive here, where I can name my pain so well that people are afraid of the consequences and power.

__________________________________

From Heart Berries. Used with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2018 by Terese Marie Mailhot.