Gay, Muslim, Refugee: On Making a Life in Trump's America

Aleksandar Hemon Tells the Story of Kemalemir Frashto

The world is full of people who left the place where they were born just to stay alive, and then to die in a place where they never expected to live. The world is sown with human beings who did not make it here, wherever that may be, though they might be on their way. Many Bosnians, and I am one of them, made it here.

In my case, the here I call my own is Chicago, where I ended up in 1992, at the beginning of the war that would make Bosnia known for all the wrong and terrible reasons. I’ve written books featuring that experience, and they were published, so I followed them around the world, where I ran into other Bosnians: Miami, Tokyo, London, Stockholm, Toronto, Paris, You Name It. I also have family in Canada, the UK, France, Italy, Sweden, Australia, etc. Bosnians are one of the many refugee nations: roughly one quarter of the country’s pre-war population is now displaced, scattered all over the globe. There is no Bosnian without a family member living elsewhere, which is to say that displacement would be essential to the national character if such a thing actually existed.

Each time I meet a Bosnian, I ask: “How did you get here?” The stories they tell me are often long, fraught with elisions, edited by the presence of the many new-life-in-the-new-land modalities. People get overwhelmed while telling them, remember things they didn’t know they could or would want to remember, insist on details that are both extremely telling and irrelevant, soaked with not always apparent meanings. Entire histories are inscribed in each story, whole networks of human lives and destinies outlined. Migration generates narratives; each displacement is a tale; each tale unlike any other. The journeys are long and eventful, experiences accumulated, lives reevaluated and reconfigured, worlds torn down and recreated. Each getting here is a narrative entanglement of memory and history and emotions and pain and joy and guilt and ideas undone and reborn. Each story contains everything I’ve ever cared about in literature and life, mine or anyone else’s. Each story complements all the other ones—the world of refugees is a vast narrative landscape.

The recent upsurge in bigotry directed at migrants and refugees is predictably contingent upon their dehumanization and deindividualization—they are presented and thought of as a mass of nothings and nobodies, driven, much like zombies, by an incomprehensible, endless hunger for what “we” possess, for “our” life. In Trumpist America, they are not only denied, but also punished for that perceived desire. But each person, each family, has their own history, their own set of stories that define them and locate them in the world, their own networks of love and friendship and suffering, their own human potential. To reduce them to a faceless mass, to deprive them of their stories is a crime against humanity and history. What literature does, or at least can do, is allow for individual narrative enfranchisement. The very proposition of storytelling is that each life is a multitude of details, an irreplaceable combination of experiences, which can be contained in their totality only in narration. I take it to be my writerly duty to facilitate the telling of such stories.

Which is why I went to North Carolina in the spring of 2017 and talked to a man named Kemalemir Frashto. This is the much-shortened version of the story he told me.

![]()

When the war in Bosnia started in 1992, his name was Kemal Frašto, and he was 18 years old. He lived with his parents and brothers in Foča, a town in eastern Bosnia, best known for its prison, among the largest and the most notorious ones in the former Yugoslavia. Foča is on the river Drina, close to the border with Serbia and Montenegro, and was thus of strategic value.

On April 4, 1992, the Frašto family prayed at their mosque in celebration of Eid, unaware that the war was about to start. That day, all the prisoners were released from the prison, and an enormous murder of crows flew up into the blue sky.

“Migration generates narratives; each displacement is a tale; each tale unlike any other.”

On April 8, the Serb forces began an all-out attack and takeover of Foča, detaining the people of Muslim background. After establishing full control, the Serbs blew up all the mosques in town, including the 16th-century Aladža mosque. Two of Kemal’s older brothers managed to escape with their families to Sarajevo. But Kemal’s father refused to leave, because he “had no argument with anybody.” Kemal and his brother Emir, nine years older, remained with their parents, only to be placed under house arrest. Serb volunteers and paramilitaries frequently and randomly came by to threaten and abuse them, and would’ve likely killed them if it wasn’t for one of their Serb neighbors, who stayed with them day and night to make sure they were safe. But that arrangement couldn’t last, as their protector’s life was thus also endangered.

Eventually, a group of Serb paramilitaries caught them alone; one of them, Kemal’s schoolmate, raped his mother. For weeks the brothers bore witness to the killing in their neighborhood: one day Kemal watched helplessly as his neighbor was slaughtered on the spot, while his wife was repeatedly raped, whereupon her rapists cut her breasts off. Eventually, Kemal and his brother were arrested and taken to the old prison which now served as a concentration camp for Muslim men.

Foča was ethnically cleansed rapidly and with exceptional brutality. The Drina carried schools of corpses, rape camps were set up all over town. Kemal and Emir shared a small cell with other men, all of them beaten and humiliated regularly. The chief torturer was their neighbor Zelja. He told the men he tortured that they’d be spared if they crossed themselves and expressed their pride in being Serbs. Kemal and Emir refused—they had lived as Muslims, and they would die as Muslims. Besides, those who complied were killed anyway. One day, Zelja broke Emir’s teeth and Kemal’s cheek bone. Another day, a guard broke Kemal’s arm with a gun butt, the bone sticking out. When, in June 1992, Emir was “interrogated” again, alone this time, Kemal could hear his brother’s begging for mercy: “Don’t, Zelja! What did I ever do to you? What do we need this for?” “So that you can see what it’s like when Zelja beats you,” the tormentor responded. Emir never returned to the cell, and Kemal never saw him again.

Zelja would be tried and sentenced in The Hague for war crimes and rape. He served his sentence, and returned to Foča, as the Dayton Peace Accord awarded the town to the Serbs, thus effectively rewarding them for their atrocities. After the war, Kemal delegated a local friend to ask Zelja for information that could help him find his brother’s remains. Zelja demanded 20,000 KM (about $10,000) to tell him where Emir’s remains were, and Kemal neither thought that he should pay up nor had the money. “I’m not a killer. It’s not for me to punish him. God will do that,” Kemal says. “All I want is to find my brother.” (Not so long ago, he finally received a tip about the place where his brother’s remains were dumped, but hasn’t been able yet to retrieve the remains and arrange a proper Muslim burial for him.)

Kemal remained in prison for 18 months, alternating between wanting to survive and hoping to die. While imprisoned, a Serb friend of Emir’s sent her boyfriend, Zoka, to find Kemal in the camp and bring him to their home for a shower and dinner. But Zoka ended up attracted to Kemal. Next time, he picked him up from the prison without telling his girlfriend and they ended up having sex. This happened more than once, and Zoka returned him to prison each time. Kemal was in closeted denial throughout his adolescence, so he lost his virginity with Zoka, the awkward intercourse with a girl forced upon him by his oldest brother notwithstanding. He now sees the sexual experience with Zoka as God-sent, something that helped him not lose his mind in the camp.

“In November 1993, there was heavy fighting near Foča and the Serb forces used the prisoners as human shields. Kemal was one of the bodies the Serbs put up in front of their positions to shoot over their heads.”

In November 1993, there was heavy fighting near Foča and the Serb forces used the prisoners as human shields. Kemal was one of the bodies the Serbs put up in front of their positions to shoot over their heads. The desperate Bosnians deployed a multiple rocket launcher to hit Serb trenches; an explosion lifted Kemal and threw him into a ditch, where he lay unconscious for a while. When he came to, he didn’t appear to be injured. It was dark, and there was no one around—not even dead and wounded—except for a beautiful, barefoot man in a white robe, emanating a kind of interior light. For a moment, Kemal thought he’d reached heaven and was facing Allah, but the man said to Kemal: “Let’s go.”

“Where am I going?” Kemal asked.

“To Sarajevo,” the man said.

Sarajevo was under siege at the time, and at least 50 miles away. Kemal walked for seven nights and six days; at night, the man in the white robe lit up the path for Kemal. He was a melek (an angel), Kemal realized, guiding him through a difficult mountainous terrain and away from combat zones. Kemal subsisted on what he foraged: wild garlic and tree leaves and carrots from abandoned gardens. At one point, he nearly stumbled upon a Serb convoy; hidden in the bushes and terrified, he watched tanks thunder by 60 yards away from him. The melek consoled him, assuring him it was not yet his time to die.

Taking a long roundabout way, Kemal reached the hills above Sarajevo, where he ran into an elderly četnik (a Serbian nationalist paramilitary group). By this time, Kemal had a long beard, which is part of the četnik appearance, so the old man assumed he was one of them. The četnik asked him where he was coming from. At that moment, what popped in Kemalemir’s head was Little Red Riding Hood (Crvenka-pica), perhaps because the old četnik’s beard gave him a wolf-like appearance. Kemalemir said he was taking food to his grandmother, which the old četnik commended. Below them, in the valley, Sarajevo was in flames. The četnik said to Kemal: “Sarajevo is burning. Fuck their Muslim mothers, we’re going to get them!”

Kemal walked on and reached the Bosnian defensive positions on the outskirts of the city. He had a četnik beard, no uniform or documents, nor could he read the Bosnian Army ranks (as it’d been founded while he’d been in prison), so the Bosnians had no way of knowing who he was, what army he might belong to. Before he passed out, he only managed to utter: “I’m exhausted. I’m Muslim. I come from Foča.”

The phrase Božja sudbina (God’s fate) is common in Bosnian, and it’s different from Božja volja (God’s will). I don’t know the theological underpinning of the difference, but I suspect that God’s fate implies a plan, a predestined trajectory laid down by God for each of us to move along without His having to do much else about it; in contrast, God’s will has an interventionist quality, and might be subject to His whims. Be that as it may, Kemal claims that it was God’s fate that his cousin was a soldier in the Bosnian unit that captured him so that he could vouch-safe for Kemal and stop the short-fused soldiers from killing him. Kemal therefore ended up attached to an infusion pouch in a hospital in Sarajevo. He weighed 88 pounds. The melek appeared to him only one more time, a few weeks later, in a dream, only to implore him not to talk about what happened to anybody.

“Kemal subsisted on what he foraged: wild garlic and tree leaves and carrots from abandoned gardens.”

In 1994, with the help of a CB radio operator, Kemal managed to get in touch with his parents, who subsequently found a way to besieged Sarajevo to be with their son. After witnessing terrible crimes and surviving, they’d crossed the border in Montenegro, Kemal’s father hiding under his wife’s skirt. In Montenegro, Kemal’s mother had discovered she was pregnant from the rape and underwent an abortion. When they reached Sarajevo, it was discovered that she had a tumor in her uterus. When it was taken out, it weighed 11 pounds.

Kemal spent the rest of the war in and around Sarajevo. He surreptitiously slept with men, including a fellow member of the mosque choir, with whom he’d meet to study the Quran. In 1995, he got a degree in Oriental studies and Arabic language at the University of Sarajevo. In 1996, desperate to leave Bosnia, he went to Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart, where his oldest brother lived. At the time, the German government, having determined that the war in Bosnia was over and that it was safe to return, emptied all the refugee camps, sending the Bosnians back. Kemal entered Germany illegally and found a job as a stripper at a (straight) bar. He enjoyed working there, as did his German lady clients, who wallpapered his sweaty body with money. He discovered and explored the very active gay scene in Cologne. At a local swimming pool, for the first time ever, he saw two men holding hands and kissing, publicly in love.

But he felt he had to go back home, even if his pockets were lined with money. God’s people lived in Bosnia, he believed, while Germany was populated with sinners. Soon upon his return to Sarajevo, he met Belma; they got married ten days later. The marriage was supposed to counter his terrible desires; he never cheated on his wife, but kept imagining men while having sex with her. He considered himself to be sick and abnormal, and kept trying to do what was expected from a “normal” man. Belma even got pregnant, but then had a miscarriage; Kemal was relieved, because the drop in hormone levels meant she lost interest in sex.

He needed a job, but his Oriental Studies and Arabic Language degree wasn’t going to get him anywhere. One winter day, after Sarajevo was swamped with snow, he went to the unemployment office to look for work, and a woman there asked him if he’d be willing to shovel. He was, and he shoveled the streets with enough enthusiasm to be offered a full-time job at Sarajevo City Services. Come spring, he was given a bicycle and a broom and assigned to the former Olympic Village, where the international athletes had stayed during the 1984 Winter Olympics. It was a good job, until his boss called him into his office to express his shock at the fact that Kemal had a college degree. Then he promptly fired him for being overqualified.

This was a turning point for Kemal. He announced to Belma that he was determined to leave Bosnia. At first she wouldn’t even consider joining him, but then changed her mind. They applied for an American resettlement visa, went through a series of interviews, and waited anxiously for a response. After two years or so, they were invited for their final interview in Split, Croatia. Kemal’s English was not good, but he understood when the interviewer asked: “What would you do if I told you that you have failed this interview?” Kemal said: “If you open that window, I’ll jump out of it right now.”

“As many refugees know, it’s exactly when things seem to be going well that post-traumatic stress disorder kicks in full force.”

In 2001, they resettled in Utica, New York, where Bosnian refugees were nearly a quarter of the population. Kemal worked at an enormous casino, and also as a cook at an Italian restaurant. He was often suicidal, and exhausted himself with work, sometimes clocking 20-hour days. But this is how life often works: in the middle of a mind-crushing depression, he and Belma went to Las Vegas, where he won $16,000 on a slot machine. He used that money to buy his first American house.

By 2003, he could no longer stand the pretense of “normal” life, and came out to his wife by way of deliberately leaving gay porn images on his computer. Belma was furious, and exacted revenge by telling every Bosnian she knew that her husband was gay, falsely claiming that he was HIV positive. The casino employed hundreds of Bosnians, and most of them now shunned him. Nonetheless, he worked out a divorce deal with Belma, from which she got enough money to move to Finland and take up with a man she had met on the internet. It turned out that the man was a human trafficker, who locked her up and forced her into sexual servitude. She went through hell, escaping and returning to the United States only with Kemal’s help.

Kemal went back to school, attained a diploma as a radiography technician. At the local mosque he met a Dr. Kahn, who told him that his desires were not sinful because God made him as he was. Kemal also met Tim, an American, and they became very close, well beyond being occasional lovers, eventually moving in together. On becoming a US citizen in 2005, Kemal merged his first name with his dead brother’s so they can always be together, his legal name now Kemalemir Preston Frashto.

When Kemalemir found a job in North Carolina, where he moved with Tim in 2007, it seemed that things were going well. But, as many refugees know, it’s exactly when things seem to be going well that post-traumatic stress disorder kicks in full force. Frequently suicidal, Kemal went from therapist to therapist—one told him that he was making stuff up, another came drunk to sessions—until he found a Muslim one, who helped him see that he was not abnormal, neither a sinner nor a monster. Kemal began reconciling his faith with his sense of himself, his innermost feelings with Islam. He understood that God created those feelings, as He created his body and its desires. Despite all that, in the summer of 2013 he attempted to “pass the final judgment upon himself” as the Bosnian idiom (sam sebi presuditi) would have it: While Tim was at work, Kemal strung a rope on the staircase and climbed the chair. As Kemalemir kicked off the chair, Tim walked in—God’s fate, again—just in time to cut the rope.

What would complete Kemal’s salvation was love. He’d been corresponding by way of Facebook with Dženan, a Sarajevo hairdresser in a sham marriage with a woman. Kemal traveled back to Bosnia to meet Dženan in person, not expecting much more than a good time, something that could get him out of his PTS doldrums. But when they met for the first time at a bus stop in Vogošća, a drab Sarajevo suburb, they embraced and didn’t let go of each other for a very long time. It felt as though they’d known each other for years, and their love grew fast. They had a great time together, and as soon as Kemalemir returned to North Carolina, he began thinking of his next visit to Sarajevo. Even so, they couldn’t quite imagine a life together; at the very least, it was logistically complicated.

When Kemalemir returned to Bosnia around Thanksgiving the same year, he devised a simple plan where Dženan, who got a US tourist visa in the meantime, would accompany him back to Charlotte, stay illegally if need be, so they could see how things between them would develop. But by this time, Dženan’s wife, became unwilling to let go of her husband and started creating problems, as did her family. Her father asked to be repaid the money he’d spent on the wedding; her sister remembered that Dženan owed her 50 KM ($25), and even she declared that if Dženan wanted a divorce it would cost him $1,000. Dismayed by the ugliness of the situation, they paid up and left earlier than planned.

“Uncomfortable though they may be in Trump’s America, they think it was God’s fate that they ended up here, and together.”

Soon upon the arrival to North Carolina they decided to get married, which would not just confirm their mutual commitment, but also resolve Dženan’s immigration status. Gay marriage was not legal in North Carolina at the time, so they went to Maryland and got married on June 12, 2014.

Until he got married, Kemalemir stayed away from the Charlotte-area Bosnians. But with marriage, he felt a need to engage with the community. He started going to the Bosnian mosque, became active and involved in the community despite their homophobia, ranging from elbow-nudging and snickering to outright insults. Kemalemir and Dženan also wanted to become registered members of the Bosnian mosque, which would, among other things, guarantee them a proper religious burial. They believed they were a legitimate part of the Bosnian Muslim community, and that there could be no viable reason why they should not be members. Some reasonable people in the community suggested to the imam that the issue be passed upward; it was eventually referred all the way back to Bosnia to be considered by a council of muftis, who then referred it back to the imam, thus completing the vicious circle. The donation Dženan and Kemal gave to the mosque was refused, their membership application denied. The imam told them that the application might have been approved had they not been so open. Kemalemir separates faith and religion and believes that, while faith comes directly from God, religion comes from man. Dženan is the love of his life, and he cannot see how God could object to that.

In the meantime, Donald Trump got elected. “I’m Muslim, refugee, gay,” Kemalemir says. “A perfect target for Trump.” After their marriage, Dženan had a temporary green card, which made them worry about the possibility of deportation, until a permanent status was approved in the winter of 2017. Uncomfortable though they may be in Trump’s America, they think it was God’s fate that they ended up here, and together.

![]()

Kemalemir told me all this, and much more, at his small apartment in Charlotte. He sat on a comfortable leather sofa facing a huge TV with programs broadcasting live from Bosnia. Next to the TV, there were pictures of the Kemalemir and Dženan grinning, a black-and-white photo of Emir, and a plaque reading:

If Tears Could Build a Stairway

And Memories a Lane

I’d Walk Right up to Heaven

And Bring You Home Again

There was also a dark carved-wood corner shelf in the dining area which Kemalemir had bought from an Iranian who at first didn’t want to sell it at any price. A few hundred years old, the wooden corner shelf was populated with ibriks, pitchers with curved spouts, and other Bosnian-style mementos. On the round table next to it, there was an intricate beige tablecloth, crocheted by Kemalemir’s mother.

In 2000, Kemal visited Foča for the first time after the war and for the last time before going to America. His former neighbors, the mother and sister of the Serb neighbor who protected his family at the beginning of it all, insisted he stop by for lunch, as they might never see each other again. When he stepped into the house, he recognized much of his family furniture: cabinets, armoires, tables. The plates the lunch was served on also used to belong to the Fraštos. “How come you have all this?” he asked the mother, if rhetorically. He knew that, after his family fled, the neighbors took furniture and other household items, claiming that if they hadn’t, someone else would have taken them. During the lunch, Kemalemir had to swallow his hurt and anger, because, he says, his mother always taught him to be the better person. But on the way out the sister, no doubt feeling guilty, said to her mother: “Give him something that belonged to them, as a souvenir,” and the mother gave him the crocheted tablecloth.

In Charlotte, Kemalemir showed me the circular area where his mother had used white thread when she’d run out of the beige kind. The shift in the color was so subtle I would’ve never noticed if he hadn’t pointed it out it to me. “This thing, this small thing,” he said, “is what makes it unique.”

__________________________________

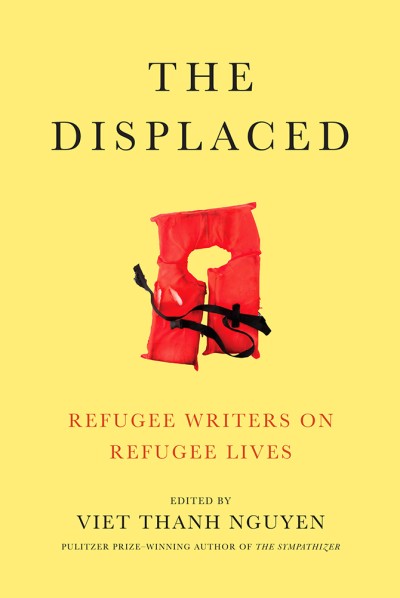

From The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives, Viet Thanh Nguyen (ed.), courtesy Abrams.

Aleksandar Hemon

Aleksandar Hemon is the author of five books including The Book of My Lives and The Lazarus Project. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a MacArthur Fellowship, and the PEN/W.G. Sebald Award.