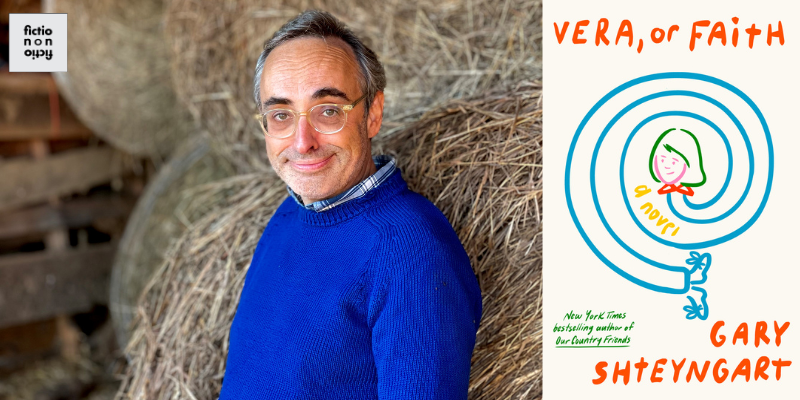

Gary Shteyngart on Vera, or Faith, and American Authoritarians

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Acclaimed novelist Gary Shteyngart joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new novel, Vera, or Faith, which explores American identity, politics, and immigrant experiences in the near future through the eyes of the eponymous 10-year-old protagonist. Shteyngart talks about the novel’s speculative “Five-Three” amendment, a proposal to give those who can trace their ancestry back to the American Revolution five-thirds of a vote, as long as their ancestors “were exceptional enough not to arrive in chains.” He reflects on how this echoes current rhetoric surrounding nationalism and exclusion. Shteyngart unpacks a scene in his novel featuring a “March of the Hated,” in which the Five-Three amendment, like the Trump administration, attracts both the privileged and those who will suffer under the policy. Shteyngart and the hosts examine the role of elite education, AI, and childhood in shaping Vera’s understanding of the world. He reads from Vera, or Faith.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/

This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, Hunter Murray, Janet Reed, and Moss Terrell.

Vera, or Faith • Our Country Friends • Lake Success • Little Failure: A Memoir • Super Sad True Love Story • Absurdistan • The Russian Debutante’s Handbook

Others:

“Tech billionaire Trump adviser Marc Andreessen says universities will ‘pay the price’ for DEI” | The Washington Post • Choice by Neel Mukherjee • “The Little Man At Chehaw Station” by Ralph Ellison

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH GARY SHTEYNGART

V.V. Ganeshananthan: These political issues are experienced through Vera’s lens. She’s in fifth grade, she’s ten, and one of the most striking features of the novel is that we see all of the politics filtered through her particular consciousness. And the politics do affect her, the social dynamics that she’s experiencing too, it’s going on at school, but it’s not necessarily the most important thing happening to her, at least in her own opinion. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about Vera. I love her character so much. Can you talk about that narrative choice?

Gary Shteyngart: Look, the book is about all the things we’ve been talking about for the past 20 minutes, but also books—Super Sad True Love Story is a good example of this—they’re always about public and private things, and the way the two intersect. This happened in part because I grew up in the Soviet Union, where everything obviously was very politicized, and I came to Reagan’s America, where things were also very politicized. Now I’m living in Trump’s America, and I also have a 10-year-old child who’s living in Trump’s America. So, these things are always in the corner of your eye.

But for Vera, there are three things that are very important. She wants to make a friend, and, God help her, this is very hard for her. She is very socially awkward, always says the wrong things—I didn’t want to make her super precocious-sounding, but she does talk a lot in a way that her peers don’t understand. So there’s that. Then, she wants to keep her parents together. Her parents are not great people, and they’re always fighting. And the third thing is, she has a birth mom and she doesn’t know who she is, and so Vera spends a lot of the book, especially the last part of the book, searching for this woman. It’s a lot of identity issues for a child of her age to deal with.

Then, as we were saying, obviously there’s also this thing where she’s about to be made three-fifths of an exceptional citizen. What makes things even more bizarre is that in school, she has to argue for Five-Three because when you’re on debate, you’re given a topic and a position, so she has to argue in favor of her own disenfranchisement, which I think is the saddest thing that can happen to a 10-year-old.

Whitney Terrell: The debate prep made me think about how important education is in shaping the way that everything happens. The ideas in this book—which seem to me, anyway, impossibly wrong, although we’re talking about how they’re already moving into the culture—but the way that you move ideas like that into the culture is in fifth grade, for 10-year-olds, right? To say, hey, let’s have a debate about this, as if it’s a thing that should be debated, which immediately lends credibility to the issue. I feel like, in the book, you’re also talking about education and the way kids learn.

GS: There’s a couple of things to think about here. I think one is, obviously the Republican Party is very interested in having less education, in defunding universities, in making sure that they don’t teach things, that they don’t concentrate on things like slavery which, how do you talk about American history without spending a lot of time dealing not just with slavery, but with Jim Crow and then the aftereffects of that? I mean, what the heck? So obviously, that’s the idea.

But Vera has a different perspective. She goes to one of these New York gifted and talented schools. I went to Stuyvesant, which is one of those high schools, and my son goes to one of those G-and-T-type schools. They’re very interesting because a lot of the kids are immigrants, many of them are from certain backgrounds. So for example, often these schools have kids from East or South Asia—and Vera, obviously, is half that—but also a lot of Jewish kids from the Upper West Side. But they’re heavily underrepresented in terms of Black and Latino students. This is a real, real issue. But in any case, these schools are very interesting, because what they do is really pit students against each other. I remember this from Stuyvesant. I was a terrible student because it was a math and science high school. They were like, “Balance an equation.” I’m like, “You balance it.” But Vera, of course, is very smart, and everyone keeps saying she has to grow up to be a woman in STEM. It’s the kind of school where at one point she gets a B+ and it’s a major tragedy. Her mom has to go into school and beg for the grade to be lifted to an A-, which is the sort of thing that happens in these schools. I remember, because my mom used to go in except it wasn’t a B+, it was a D+, and my mom was trying to get it to a C- or something. So all this feels very relevant to me.

All these schools are very different, of course, but it’s a question of, what are you educating for? It’s all competition, it’s all memorizing and remembering things, it’s all figuring out who the next elite in finance and tech is going to be. The reason I think that happens is because the pie is getting smaller and smaller, and people are more and more freaked out—the master’s degree is now the new bachelor’s degree. Especially with AI and other things, people are more and more freaked out. The importance of education, not as something that you learn so that you can become a better citizen, a better human being, but—we’re learning a value structure. In fact, the value structure is inverted, because you learn how to make more and more money, and that’s the only thing that matters. And then as you make more and more money, your priorities become Marc Andreessen priorities, right?

VVG: There are so many moments in the book when Vera is at school where I had this terrible feeling of recognition and sympathy. There’s a moment where she got the right answer to a math problem, and then she calls it out. I think my heart just shattered in my chest, because she’s right, and the teacher’s like, “Not only do we not call out, but we don’t call out wrong answers.” Brutal.

GS: For many of us who have been through this dog-eat-dog type of education, I think this really rings a bell. It’s interesting, this book also reminds me, who are readers of literary fiction? There’s not a lot of them left, but there’s some of them left, and it’s almost a given that they were super anxious as children. You don’t become a major reader without being anxious and sensitive as a child, right? I’ve already been giving readings where some people have read the book, and many of them are women, and I say to them, “Does Vera remind you of you when you were ten?” and they say yes, so I feel like they’re seen when they read this book. Because all of us who were readers then, and still are readers, grew up feeling very anxious. In books we found a home amid characters that reminded us of ourselves and also of the many struggles that we face, being a little different or a lot different, in my case, being weird, often not knowing the language. In the case of immigrants all that stacks together.

VVG: This is maybe the second time recently where I felt a sharp recognition of my own anxiety in a novel, the other one being the first part of Choice by my friend Neil Mukherjee. I was like, “Oh, my God, my anxiety is on the page in a way that I can hardly cope with.” Then Vera is preparing for this debate, and she doesn’t want to be competitive, and she doesn’t find much sympathy for that, either.

The Trump administration is clearly trying to rearrange the ways that Americans think about what it means to be American. There are so many great American thinkers. This podcast started because Whitney and I are connected through our mutual former Professor Jim McPherson. We talk a lot about Ralph Ellison on the show. The mixing and melding of cultures is something that is a hallmark of these kinds of thinkers, these definitions of what it means to be American. You immigrated to the U.S. like my parents did. What was your understanding of what it meant to be American when you came here? How has that changed? Because seeing that refracted through Vera is so interesting.

GS: I came during a time when—Russia, the Soviet Union, it’s always a mess, and it’s always not a great society, but this was the Ronald Reagan evil empire era of the early ’80s and I spoke with an accent, I had a giant fur hat from Russia, so things were not cool. Also, I went to a school where most of the kids were upper-middle class, and we were very clearly not. My grandmother would get food stamps and government cheese, which I actually really liked back in the day. Anyway, it was this very strange homecoming.

I really didn’t feel American until I went to Stuyvesant, where at least half the kids were of immigrant status. Now, I think it’s more like 80 percent but, huge amount of immigrants. Even though I sucked at the academic part of it, I felt like, “Oh, this was my cohort because they’re all bringing weird, smelly lunches, eating buckwheat kasha and kimbap.” That felt much more at home to me. My last book, Our Country Friends, was a gathering of five or six immigrants of my generation, from India, Korea, Russia, someplace else. That felt like it was an important book because we were all that generation. Now we’re in our 40s and 50s, and some of us have children too, so it’s interesting to see. Vera is almost—it’s not a sequel to that, but it’s the next generation.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Gary Shteyngart by Tim Davis.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.