FX’s Great Expectations Doesn’t Measure Up

Steven Knight’s Miniseries Makes Interesting Points About Empire and Womanhood, but They Get Lost in a Sea of Gratuitous Darkness

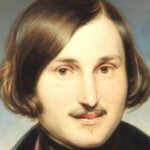

I’m not above saying that I had greater expectations for Great Expectations, the new six-part miniseries from Peaky Blinders creator Steven Knight. I did. Charles Dickens’s 1861 Great Expectations is more than a classic novel; it’s a tremendous achievement on its own, but as source material, it is as rich a wedge of atmosphere and characterization as they come.

My heart goes out to the writers of this new one, as it does for every Dickens adaptation, because it’s not an easy task transforming Dickens’s long, atmospheric novels, with their millions of characters and abundance of motivated subplots, to a medium that had not yet been invented when they were conceived. It’s also not easy because there have been so many adaptations of Dickens—so many adaptations of Great Expectations. The impulse to keep the audience from getting lost amid the countless narrative capillaries is just as powerful as the urge not to allow one’s version to get lost amid the sea of myriad versions. Truly, I sympathize.

Feelings about decipherment and derivation aside, though, I found myself quickly wondering what the point of this new one was. That being said, this new Great Expectations, a co-production between the BBC and FX, makes a lot of changes, and some are genuinely thought-provoking.

For example, the adaptation slips in criticisms of colonialism and empire which at the very least provide useful commentary, de-isolating a nineteenth-century story from aspects of its nineteenth-century context. That thematic investment on its own could have bolstered the story, close-read a story we’ve read before and shed some new light.

However, much of the adaptation seems to be an exercise in how much—and what—else can be crammed into a Dickens story. I’m not just talking about violence (of which there is no short supply in virtually any of Dickens’s original stories, anyway). But the scripts eschew Dickens’s careful, moody plotting for superfluous exposition and redundant asides, like how at the beginning, we have to watch Magwitch (Johnny Harris) escape from jail in a brutal and pyrogenic prison break sequence that lasts almost ten minutes. It’s a meeting that could have been an email, and this is a tone that persists throughout.

I’m not a stickler for textual fidelity, but I do wonder why the carefully cultivated economy of Dickens’s original story wasn’t satisfactory, especially because what replaces it is cumbersome and, at times, boring. By the time Pip (Tom Sweet) shows up to his family’s gravestones and is confronted by the convict Magwitch (which happens in the fourth paragraph of the first chapter), one-third of the first episode is already gone, and we’ve spent a lot of it watching Magwitch run breathlessly through a swamp.

It’s clear that Magwitch is being framed as a counterpart to Pip, which is interesting, but making him a prominent figure from the get-go, rather than a specter of Pip’s grim early environment, robs him of the chance to embody the novel’s big plot twist, towards the end. Obviously, every adaptation requires sacrifices, but is this the one? I don’t know. Only the first two episodes have been made available so far.

You probably know what it’s about, but since redundancy’s on the table, what the hell: Great Expectations is about a young, poor orphan named Pip who lives with his abusive elder sister Sara and kindly brother-in-law Joe, who receives a surprising bequest and is taken to become a gentleman. There, he stays at Satis House, home of Miss Havisham, who was jilted at the altar many years before and has remained in her wedding dress ever since.

Miss Havisham has a ward, the lovely Estella (Chloe Lea), whom she trains to capture the hearts of men and then destroy them, to “wreak revenge on all the male sex.” Pip is her first specimen in this effort, and it is a successful trial; he falls in love with her and she keeps him on the hook forever. When they grow up into Fionn Whitehead and Shalom Brune-Franklin, their dynamic is positively torturous.

It seems like the objective of Knight’s Great Expectations was to produce a gritty underbelly to a story whose plot revolves around joining high society; it is full of dirty, grimy, crass details, lots of “fucks” and blood. It’s a real “what-people-misinterpret-about-Fight-Club“-minded Great Expectations, all savage brawls and anger and carnality. This can really work for Great Expectations in smaller doses, but its excursiveness turns the effort into something supercilious.

But the strangest thing in this Great Expectations is how over-written it is. We must hear over and over again how Pip loves books and he feels lonely because he wants to quote Shakespeare while working at Joe’s blacksmithing shop. It’s not even that the point of the novel Great Expectations is that Pip is uneducated from the get-go, but it’s unclear why adding an apparent thirst for knowledge does anything for the plot or the character. Is it to draw attention to class divide, as if the rest of the story doesn’t do that already?

The best part are the performances, namely Olivia Colman as a genuinely terrifying Miss Havisham, whose wedding gown and veil don’t look so much yellowed or decayed as haunted, and a resplendent Matt Berry as the peacocking Mr. Pumblechook. Colman lights up the (very dark) screen as a Miss Havisham who is more creepy than pathetic, more monsterous than calcified. Her performance is positively bloodthirsty; she looks at Sweet and Whitehead as though she wants to take bites out of their flesh. It’s an interesting reading to put forth so clearly that Miss Havisham not only despises men, but also hungers for youth—to represent her as generating so much activity from her forced passivity.

Knight’s Great Expectations is an eerie, vicious, and occasionally offensive production, which, while it seems to be its intention, steamrolls over its genuinely interesting contributions, notably about empire and womanhood. But all of that gets lost amid the the shocks and blows, the relentless, brassy cruelty and vulgarity. I’m sad to say that it is, ultimately (and here’s some Shakespeare for you Pip) “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” I’m sorry for it, too.