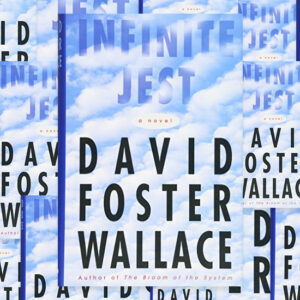

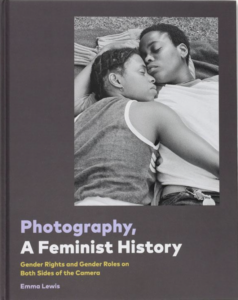

From the Outside-In: Who Has the Right to Photograph a Community?

Emma Lewis on Feminist Photography and Storytelling

In a 1976 article for British magazine Camerawork, photographer Jo Spence laid out the problems she saw in the two dominant forms of socially realistic photography of the time. One was photojournalism, which she described as voyeuristic, one-sided and “lacking in meaningful social or political perspective.” The other was photography for charities, which she said was inevitably undertaken by photographers who were of a different social class to their subjects, whose lives they depicted in the bleakest way. Disillusioned by this state of affairs, Spence advocated for photographers to adopt a different way of working, suggesting they embed themselves within communities to create a more nuanced and in-depth representation of their participants’ lives.

Community photography, as it became known, was not new. But in the context of 1970s Britain—in the immediate aftermath of the miners’ strike of 1969, and amid ongoing workplace unionization and the fight for women’s rights—defining this position was a political statement. Many photographers worldwide had adopted the same approach. By working from within, they could go beyond mainstream narratives to reveal how issues played out for women day-to-day, or show aspects of their lives that went unreported altogether. Although no-one claimed that this approach was inherently or automatically feminist, awareness of the ethics involved in accessing another person’s space was an important part of taking a feminist approach. So, too, was what they noticed while they were there.

Spence co-ran the socially motivated initiative Half Moon Photography Workshop, which was rooted in the recording of life and local matters. In the same issue of Camerawork, the Workshop published a statement of aims, explaining that their central concern was not “Is it art?,” but “Who is it for?”

At a time when the line between documentary photography and fine art was becoming increasingly blurred, this question cut to the heart of a particularly lively debate. In the UK in the 1970s, as elsewhere around the world, there was a slow but steady growth in the forums in which one could publish and display one’s work and have critical conversations about photography. In-depth stories about real lives were no longer found only within the pages of newspapers or magazines, but increasingly seen in photobooks or displayed on gallery walls. Tentatively (and admittedly unevenly, depending on the country), collectors’ markets were becoming established, too.

“There is a popular notion that the photographer is by nature a voyeur, the last one invited to the party. But I’m not crashing; this is my party.”

The gradual visibility of photography within exhibition spaces was a big deal. Photography had previously been treated as the poor cousin to the rest of the visual arts, and to an extent it still was. “There’s nobody out there rooting for photography. It’s under-funded and under-stated,” wrote the co-ordinators of London’s 1988 Spectrum Women’s Photography Festival, one of many events whose existence reflects that women photographers felt doubly marginalized. In the few instances where spaces were created for photography, they were overwhelmingly allocated to men. Street and documentary work by Tish Murtha and Shirley Baker—who each chronicled communities in the North of England and London—took decades to be given due credit.

For those who were working in the documentary mode, the logistical problem of getting one’s work seen was one thing. Negotiating complex questions about what it means to treat socially engaged images as objects of aesthetic interest instead of, or as well as, photojournalistic dispatches, was quite another. What does it mean to show such work in spaces that the individuals depicted may never enter? Or for those individuals not to materially profit from those images? Ultimately, when it comes to making public images of private lives, what are the responsibilities of the photographer toward their subject?

Bound up in these questions is another: what is the photographer’s relationship to the community they are depicting? Are they shooting from the inside, or are they on the outside looking in? In the introduction to her book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986) Nan Goldin preempted this idea when she stated: “There is a popular notion that the photographer is by nature a voyeur, the last one invited to the party. But I’m not crashing; this is my party.”

The question of who is telling whose story is no less relevant today; if anything, it has taken on fresh urgency. It raises the issue of uneven power dynamics and notes that traditionally there has been a tacit understanding that the person wielding the camera has greater power and agency than the person in front of the lens. It articulates, too, important concerns about the potential for the misrepresentation, even exploitation, of the individuals depicted. Yet, at a basic level, this line of interrogation can be a blunt tool. It can suggest that an outsider’s perspective cannot be valid or, at the other end of the scale, that the perspective of one insider can somehow represent that of their entire community—neither of which holds true. This is not to say that question is not an important, even vital, one. Rather that, taken alone, it can risk oversimplifying the photographer-participant dynamic.

What are the principles with which the photographer approaches their subject?

Throughout histories of 20th- and 21st-century photography, there are many examples of photographers whose sensitive documentation of different communities cannot be easily explained by whether or not they possess the position of “insider.” Mao Ishikawa’s portraits of the lives and loves of herself and her friends in American-occupied Okinawa from 1975 to 1977, for instance, are a rare testament to a poignant moment in social history but also her personal life. By contrast, Paz Errázuriz did not share the lived experience of the trans people and their families, whom she spent seven years photographing during Chile’s military dictatorship. Still, creating the series in the knowledge that censorship laws would mean it was seen only by a few, it became a record for posterity and, first and foremost, for the people she depicted.

Another case in point is that of Liz Johnson Artur. Since the 1980s, Artur has documented people of the African and Caribbean diasporas at family celebrations, on the street, and in public spaces from club nights to places of worship not only in her neighborhood of South East London, but also much further afield. Although she rarely knows the people in her photographs, it is they who her work serves. She has said that her approach is a “direct exchange [and a] way of ignoring this perspective of the ‘other.’” Her idea of community is sprawling and expansive, global as well as local, personal as well as anonymous, resulting in what has been called “a family album for the diaspora.”

*

To begin to navigate the ethics involved in community-centered work, then, the discussion cannot start and end with whether a photographer “belongs to” the community they are depicting. A more constructive and open-ended line of inquiry might be, “what are the principles with which the photographer approaches their subject?” What, as Artur describes, is the nature of their exchange?

Susan Meiselas—an outsider to the communities she documents, although typically she works with them for months, years, or even decades at a time—is renowned for her rigor on this topic. Guided by a concern about who is best served by her images and the responsibilities of the photographer toward their subject, she has repeatedly spoken about being “invited in” and emphasizes the importance of collaboration. Describing her work with survivors of domestic abuse in England’s Black Country, she said: “Only when I actually entered a refuge and found openness to start a dialogue, did I begin to imagine creating work that could connect women whose lives had been most deeply impacted.”

Chloé Jafé has similarly shown how, by forging relationships and slowly gaining trust, the individuals a photographer depicts can become active participants in their representation rather than passive subjects. Her uniquely intimate, non-sensationalist portraits of the wives and girlfriends of Japan’s Yakuza, an organized crime syndicate, resulted from immersing herself in their world over many years: she worked in a bar they patronized, built close friendships, and slowly but surely learned to negotiate complex clan hierarchies.

When it comes to community-centered projects, then, there cannot be one single approach or subject that identifies a project as “feminist”—but there are certain characteristics we should look out for. For, if intersectional feminism is about understanding that different groups and individuals experience power and oppression, advantage and disadvantages in different ways, then a feminist approach is attentive to how these structures are manifest in documenting the lives of others, and how these images are circulated into the world.

__________________________________

From Photography, A Feminist History by Emma Lewis, published by Chronicle Books 2021.

Emma Lewis

Emma Lewis is an assistant curator of international art at the Tate Modern in London.