From the Margins to the Mainstream: How the Synthesizer Conquered American Music

David Hajdu Explores the Creative and Technical Evolution of a Versatile Electric Instrument

Our conceptions of artifice and authenticity have always been mutually dependent. Ever since machines began to change the world and the way humans have thought about it, establishing the idea of the natural in opposition to the mechanical, new mechanized or electronic ways of doing work and making art have redefined the methods that preceded them or, in some cases, defined the old ways for the first time.

Music played by an automated man in a Piccadilly music hall got listeners thinking about what it was that they had relished in music made by a living player. From then on, if real people were to make music like that of a machine, it would be thought of as unreal, untrue—not merely new or different, but, by association with machinery, inauthentic: lesser. Artworks produced by industrial methods such as the silkscreen portraits of Andy Warhol and the plywood constructions of Donald Judd, or the abstract ink drawings made by a computer programmed by Michael Noll, crystallized what art lovers had valued in the work of human hands.

Artifice alters reality—or our understanding of it. And sometimes, synthetic things become the new reality—or part of it. With time, some kinds of art and music that seemed unnatural or unreal at first become familiar and eventually commonplace. They seep into the fabric of the world we know and settle into it, become a piece of it. In music, this happened over the course of the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century, when a family of electronic technologies moved steadily from the fringes of novelty attraction and the avant-garde to the heart of mainstream culture, changing the way a great deal of music was made and what listeners made of it. The main character in this story is a device named for its ability to fabricate music artificially, producing sounds that are, by definition, synthetic.

With time, some kinds of art and music that seemed unnatural or unreal at first become familiar and eventually commonplace.

In the fall of 1968, the term “synthesizer” was still largely unknown outside of laboratories for the electronics and chemical industries. An early Moog synthesizer was set up to serve as a freaky-looking prop for a scene with Mick Jagger in the hippie freak-out movie Performance, and one of the technicians on the set called it a “sanitizer,” having no idea what it was. The Moog in the film was Jagger’s own property, though he never used it with the Rolling Stones. The bits of synthesizer music blipping and whizzing in the background of a few scenes in Performance were performed by Bernie Krause, a former student of electronic music at Mills College.

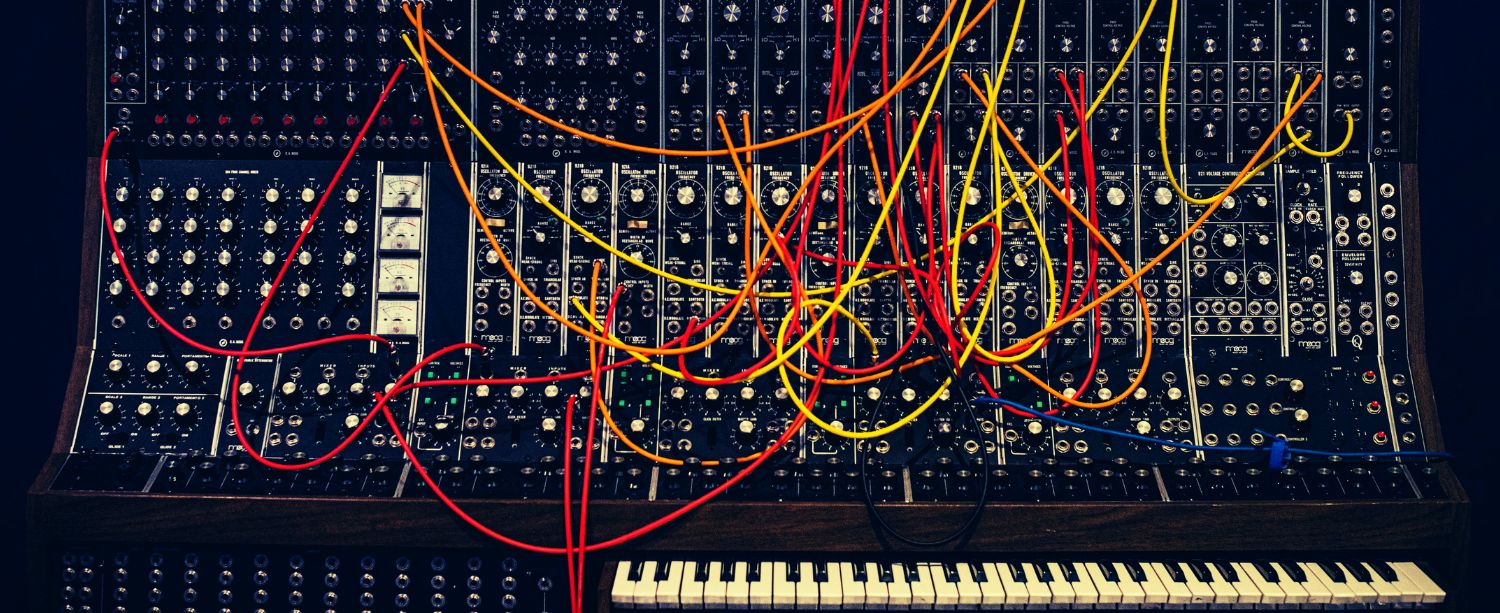

Krause was working in a two-hatted role as performer/sales representative for the R. A. Moog Company, manufacturer of the eye-catching and ear-stretching sound-synthesizing equipment devised only five years earlier by a thirty-year-old Cornell PhD student with the name of a wizard from Mars, Robert Moog. Krause and another musician, Paul Beaver, would tote the stove-size early synthesizers to potential users and demonstrate them and give lessons in using them, in hopes of making deals to sell them. Beaver and Krause had the wisdom to pitch creatively ambitious and very wealthy rock stars like Mick Jagger on the virtues of a bizarre new machine that cost almost $15,000 and was oppressively difficult to play but looked super-cool.

While MoMA and the Brooklyn Museum were setting up their simultaneous shows of mechanical, electronic, and hybrid visual art in New York, George Harrison was in Los Angeles, stepping away from the Beatles temporarily to produce an album for Jackie Lomax, a blue-eyed-soul singer from Liverpool he had signed to Apple Records, the label the Beatles had recently formed. Harrison, acting for the first time as producer for another artist, booked the crème of California studio musicians, a loose assemblage of rock pros associated with Phil Spector sometimes called the Wrecking Crew.

On the last day of sessions, November 11, Bernie Krause and Paul Beaver came to the studio to show Harrison how the Moog synthesizer could be used to add unusual electronic textures and filigree to the recordings. When the sessions were finished, late that night, Harrison asked Krause to stay and give him a private demonstration of the Moog: How many different sounds could it make? What did the operator have to do to make them? Krause proceeded to walk Harrison through the range of electronic tones the Moog could produce—one at a time, since the device could generate only single notes, unable to play chords or even two notes simultaneously.

Press one of the keys on a keyboard attached to the array of interconnected components covered with knobs, plugs, and switches, and the Moog would produce a low, rumbling growl. Turn a few knobs, and out comes a fizzy hiss. Flick a couple of switches, and the hiss would start to wiggle. Turn another knob, and the wiggle would slow down and stretch out to be a wobbly warble. Run the tip of your finger along a stretch of metal ribbon, and you would hear a siren rising higher and higher and higher in pitch. Plug in a couple of plugs, and hear a staticky, ratchety sound unlike any sound in nature. Krause kept turning, flicking, plugging, and unplugging, and out came a cartoon circus parade of random gurgles, squiggles, bleeps, chirps, honks, howls, and noises without English words to describe them properly.

Harrison was impressed and drawn to the exotic, otherworldly aura of this baffling machine for making extra-human music and sound. Famous for bringing dimensions of Eastern mysticism and Indian classical music into the sphere of the world’s most popular band, he had recently produced a film score that foregrounded South Asian musicians in an aural mosaic with Western pop elements. The soundtrack album, Wonderwall Music, had just been released as the first solo album by any of the Beatles.

Open to avenues of creativity as yet unexplored by other pop artists—including John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Ringo Starr—Harrison placed an order to buy the same model of synthesizer he had seen and heard in Los Angeles, the Moog IIIp. He asked Bernie Krause to have the equipment shipped to the English county of Surrey, where he was living in a low-roofed bungalow with exterior walls painted in swirling patterns of psychedelic colors: wonder walls! Now, with a Moog, the inside of the house could sound like the outside looked.

“It was enormous, with hundreds of jack plugs and two keyboards,” George Harrison said of his new acquisition. “But it was one thing having one, and another trying to make it work. There wasn’t an instruction manual, and even if there had been, it would probably have been a couple of thousand pages long. I don’t think even Mr. Moog knew how to get music out of it.”

Unable to do much with the Moog on his own, Harrison summoned Krause to England for a personal tutorial. As Krause prepared to instruct Harrison in the use of frequency oscillators, control voltage attenuators, wave multipliers, and trigger sequencers, Harrison broke the news that he was planning to release a full LP of synthesizer music on Apple Records’ subsidiary label for art music and spoken-language recordings, Zapple, which John Lennon and Yoko Ono were using for their latest experiments in tape loops and found sound. In fact, Harrison continued, he already had a full side of the album completed. “I want to play something for you that I did on a synthesizer,” Harrison announced, as Krause would recall. “Apple will release it in the next few months. It’s my first electronic piece done with a little help from my cats.”

Harrison played the tape, and, after a minute, Krause recognized what he heard. Back in Los Angeles, when Krause was walking through a raw demonstration of Moog sounds after the Jackie Lomax sessions, Harrison had the studio tape recorder running without Krause’s knowledge. Now, he was planning to release an edit of the demo as an electronic composition. “George, this is my music….Why is it on this tape, and why are you representing it as yours?” Krause asked.

“Don’t worry,” Harrison replied. “I’ve edited it, and if it sells, I’ll send you a couple of quid.”

The album Electronic Sound was released by Zapple Records under George Harrison’s name in May 1969. The front cover was a fun, brightly colored acrylic painting by Harrison himself, done in the same ebulliently naive style as the cover painting Bob Dylan had done for the debut album by The Band, Music from Big Pink, the previous year. Harrison’s artwork depicted, in its way, a man with green skin and bright red lips, wearing a yellow bow tie, surrounded by Moog components. (In liner notes for the reissue on CD, Harrison’s son Dhani said the green-faced person was his father’s image of Bernie Krause.) The man is positioned behind a big control panel, the front of which is overladen with abstract designs: pink squiggles, green and white dots, something like a shooting star or a fish, and a red Jewish star—presumably an allusion to Krause—with the spout of a meat grinder on one side, spewing out sounds.

The record had two selections, each filling a side. One was the recording of Krause’s Moog demonstration in Los Angeles, edited to about twenty-five minutes in order to fit on a vinyl LP and given the title “No Time or Space.” That was a phrase Harrison had used in interviews to convey the experience of Transcendental Meditation. The other track had actually been generated by Harrison on his Moog: a sequence of elementary synthesizer effects, seemingly disconnected, which Harrison titled “Under the Mersey Wall.” (That was a twist on the title of a column in the Liverpool Echo newspaper, “Over the Mersey Wall,” written by an unrelated writer also named George Harrison, as well as a vague claim to underground status.) On pressings for the U.S., the titles on the record labels were inadvertently reversed. A credit line for “No Time or Space” read “Recorded with the assistance of Bernie Krause.”

As Krause would later say, “I had no control over any of it. I didn’t know it was being recorded. I didn’t want it out, and I felt very badly that he had to do that.”

Electronic Sound did not sell copies sufficient in number for Harrison to send Krause any amount of quid. Within weeks of the album’s release, the Beatles’ new business manager, Allen Klein—a hard-nosed philistine with the interpersonal style of a scrap-metal shredder—shut down support and funding for Zapple Records with no public announcement. Electronic Sound went unpromoted and virtually unnoticed, never appearing on the UK sales charts and poking up for only two weeks near the bottom of the US Billboard chart, peaking at number 191 out of 200.

In the Rolling Stone record review section, critic Ed Ward took up Electronic Sound briefly at the end of a piece focused mainly on the only other album released on the very short-lived Zapple label, John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions. Ward tore into Lennon and Ono’s album, the second of their three releases of sonic experimentation, which included a recording of the fetal heartbeat of the couple’s unborn baby, taped on cassette before Yoko miscarried, along with an edit of a live performance Lennon and Ono gave with a couple of free-jazz musicians at Cambridge University. Ward dismissed it as “utter bullshit.”

He was gentler with Electronic Sound. Unaware that another person was playing on one of the two tracks, he gave Harrison some credit for doing “quite well learning his way around his new Moog Synthesizer in such a short time,” adding, “but he’s still got a way to go.” The album “is fair enough as a beginning effort, and although one can imagine George sending tapes of it to his friends, it is hardly musical product,” Ward wrote. “The textures presented are rather mundane, there is no use of dynamics for effect, and the works don’t show any cohesiveness to speak of. However, if he’s this good now, with diligent experimentation, he ought to be up there with the best in short order.” In a poke at the albums’ pretentiousness, the review was credited to Edmund O. Ward.

An edgier semi-underground magazine called Fusion, published out of Boston, took a properly unconventional approach to Electronic Sound with a bitingly mimetic review by Loyd Grossman, a Massachusetts-born writer who would later relocate to London and become well known as a cultural broadcaster. This was his review, in its entirety:

THIS ALBUM…phlurp phlurp phlurp…is on Zapple (grauughh! *’&’%%!) the Beatles personal label /--perhaps no othercompany wapwapwapwapwapwap uuuhwweeoques—would record it-++++++++++++

The ALBUM was composed (??????????) and produced (!*

@3#+”_#) by George kpowie kpowie uuuuuuuummmm HarrisOn;,V2#$. It has zigazigazigaziga z i g a z i g a z i g a aaa two sides and is made of AS cEEERP!EEERP!EEERPPPPPPP! and comes with a lble(oopsO) label and a cover @@@@twerptwerptwerptwerp @@@ and is 4three minutes and 50+1 seconds long, which bzzzzzzbzzzzzzbzzzawwww is a lot of ;5;5;5;5; nois-e ¢¢;#;¢. As an extra twyehdgeysgetdfefcbruhebdtefsf bonus it is ROUND and oooooooooopppawwwiee water resistant S O THAT when you are t h r u h--------- listening to it;;;it can be used as a meeooom porthole cover……………….If YOU fweemfweemfweemfweem apapapapapapap have an olD Sunbeam Toaster ugwachattttattachurgchurg churg and enjoy putting your dddddldddlddlllder ear up to it wwhoooooooggggg*-*- you may enjoy this album phwerpphwerp phwerp phwerp phwerp phwerp phwerp phwerp phwerp.%.%.@V4:!*.—L@yd gr¢ssM&n

Music synthesizers have been around as long as musical instruments. In a sense that is not just playing with terminology, all instruments have always been synthesizers. As a rule, they aim to replicate sounds from the natural world—to synthesize those sounds, as a piccolo conjures the sound of birdsong or a saxophone evokes the sound of the human voice; or they aim to produce sounds not to be found in nature—artificial sounds, synthetic sounds.

Beyond the domain of such traditional instruments, meanwhile, a whole class of electronic keyboard innovations emerged in the mid-twentieth century for the purpose of emulating the sounds of as many other musical instruments as possible while, on top of that, generating new kinds of sounds no other implements could produce. They had antecedents in the dozens of makes and models of opulent music machines popular in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century: the orchestra boxes such as Rex, the Popper company’s Orchestrion that’s still entertaining school trip audiences at the Morris Museum in New Jersey. In time, the electronics of the vacuum-tube era led the art of music synthesizing to advance considerably, and wonders of the Mechanical Age like Rex took on a new kind of wonderment as antique curios.

The first electronic keyboard instruments designed to synthesize the sounds of multiple other instruments were essentially smaller, vacuum-tube versions of the mammoth, intricately engineered pipe organs that had long brought the variety of aural colors, the volume and force, and the grandeur of the symphony orchestra to cathedrals and other houses of worship, concert halls, and one major department store, the block-size Wanamaker store in Philadelphia. (The role of popular retail outlets as commercial parallels to houses of worship in America has been obvious since the heyday of department stores in the mid-twentieth century.)

The Wanamaker organ, still working after 120 years in operation and played regularly in the third decade of the twenty-first century, is said to be the largest fully functional pipe organ in the world. Built for the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis and later purchased by John Wanamaker to draw floor traffic in his store, the organ is monumental in scale and complexity, with six keyboards and more than a hundred hand and foot controls, 27,750 pipes in 464 configurations spread out in space in five floors of what was once the Wanamaker building, now owned by Macy’s.

In a public talk before a tour of the organ and performance in January 2020, a representative from the store recited a litany of impressive factoids about the instrument and its history. “Leopold Stokowski was so inspired by this organ that he commissioned works to be played on it,” the guide said. “Composers of note like Richard Purvis and Marcel Dupré were so moved by it as to compose works specifically for the organ. A number of notable music works wouldn’t exist were it not for this organ. The organ didn’t create the music, per se, but it inspired the compositions.

“It takes several months of dedicated study of this organ and practice to be prepared to play it to its full capacity,” he added a few minutes later. “There are currently only two or three musicians in the country qualified to sit down right now and play it to capacity. It’s not like playing a Casio.” That a small Casio keyboard could simulate a great many of the Wanamaker organ effects is an additional fact the guide did not mention, though no electronic instrument of the digital era could be expected to come anywhere close to competing with the resonance and dynamic impact of 27,750 pipes spaced over five floors of a building.

The road from the Wanamaker organ to Casio keyboards is dotted with technological landmarks, and the Moog synthesizer is surely foremost among them. More than twenty years before the Moog, however, another electronic synthesizer, now all but forgotten, received a good amount of attention and deserved it. Invented by Laurens Hammond, who also developed an electric organ and marketed it through a company carrying his surname, the first popular synthesizing instrument was called a Novachord, a fitting name for a machine that produced electric-textured polyphonic chords designed to suggest the eruption of a nova. (Once again, the first Moog synthesizers would not be capable of playing chords at all.)

The term “synthesizer” was not in the musical vocabulary when the Novachord was introduced, in 1939, but the concept of synthesis was in the air. The synthetic products of synthetic processes had entered the national conversation, with human-made fibers beginning to transform the garment industry needed for parachutes. A synthetic silk called nylon was appearing in women’s stockings just as wartime rationing was limiting supplies of natural silkworm products.

Separately, a pair of British chemists, James Tennant Dickson and John Rex Whinfield, developed a new polyester material for use in fabrics. The American company Dupont bought the rights to it, twiddled with the formula, and introduced it under the brand name Dacron in 1941. In the same period, advances in pharmaceutical chemistry were leading to the development of groundbreaking synthetic drugs: synthetic hormones and antibiotics. Chemists and clothing manufacturers and medical scientists were all busy synthesizing. Why not musicians?

The Hammond company introduced the Novachord to the public in a futuristic setting: the Ford Pavilion of the 1939 World’s Fair, with the composer Ferde Grofé conducting four musicians playing three Novachords and a Hammond organ. Early observers found the instrument “amazing and startling,” the New York Herald Tribune reported, explaining how it “resembled the piano but can be played to stimulate the sound of nearly any musical instrument,” from “the brassy blare of the trumpet” to “the clear call of the English horn” and other less alliterative phenomena. As the composer John Cage would note, “Most inventors of electrical musical instruments have attempted to imitate eighteenth- and nineteenth-century instruments, just as early automobile designers copied the carriage.”

Laurens Hammond stressed the more distinctive ability of the Novachord to produce unique, unconventional electronic sounds. As an Associated Press report pointed out, “Its inventor does not consider it an imitative instrument in the sense that it would be substituted generally for any of the instruments whose voices it can produce. His idea is that it brings to music entirely new possibilities which will be developed for varied orchestra effects and for greater diversification and interest in home entertainment.”

This approach made good sense politically as well as aesthetically. Almost immediately after news of the Novachord broke, the existence of a single instrument capable of doing the work of a dozen others triggered panic at the American Federation of Musicians. The union announced a sweeping prohibition of public use of the Novachord by its members. Within weeks, Hammond lobbied successfully for a compromise whereby an AFM musician would be permitted to use the instrument professionally under a set of detailed conditions, such as only if the Novachord were not taking the place of a different instrument and only if the Novachord were not being used on a type of job that had previously called for the use of multiple instruments. The fear of machines taking over for humans is one of the great constants in the history of technology, and it is equally easy to inflate or dismiss.

In part because it didn’t really sound very much like a trumpet, an English horn, a Hawaiian guitar, or any of the other instruments it sought to emulate, the Novachord was generally used for the wholly unique sounds it could produce. The British singer Vera Lynn, heartthrob of the Kingdom’s boys in uniform, had a major hit with a ballad of romantic yearning, “We’ll Meet Again,” sung to the accompaniment of a Novachord providing a wash of supernatural-sounding tones.

With the spectral quality the Novachord brought to the recording, Lynn seemed to be assuring both soldiers and loved ones waiting on the home front to take heart: they will be reunited one day, if only in the afterlife. (On the record label, the singer, the keyboard player, and the instrument received roughly equal billing, with the names of all three printed in capital letters the same type size: VERA LYNN with ARTHUR YOUNG ON THE NOVACHORD.) Along the same lines, the film composer Franz Waxman used the Novachord for ghostly effect in parts of his score for Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca in 1939, and Max Steiner employed it in a similar manner, though more subtly, in the entr’acte of his music for Gone with the Wind in the same year.

Pop and jazz composers with advanced senses of humor used the startling tonalities of the Novachord in clever ways, leaning into the instrument’s oddity. Slim Gaillard, a composer/singer/multi-instrumentalist known for blending improbable combinations of ingredients on recordings like “Mishugana Mambo” and “Sukiyaki Cha Cha,” showed that the strange new machine could swing with a juke-joint kick on his record “Novachord Boogie.” In a kindred spirit, a virtuoso whistler and rhythm-bones player named Freeman Davis, working as Brother Bones, revived a standard of the Charleston era, “Sweet Georgia Brown,” with Novachord backing. The record was an unpredictable hit of unlikely durability, played countless times for decades as the theme song of the basketball comedy act the Harlem Globetrotters.

Music synthesizers have been around as long as musical instruments. In a sense that is not just playing with terminology, all instruments have always been synthesizers.

The Novachord, made with 163 vacuum tubes and more than a thousand capacitors hand-wired and individually soldered, was time-consuming and expensive for Hammond to produce, and costly for users to purchase and maintain. Encased in a cabinet of cherrywood, each instrument weighed about 500 pounds and cost $1,900 in 1939 (about $24,000 today). The price of a Novachord was almost exactly half the average cost of a new home in 1939. After three years on the market, only 1,069 Novachords were sold, and manufacturing expenses were rising with wartime restrictions on electronic components. Hammond discontinued the Novachord in July 1942, shifting its focus to the electric organ market.

After the war, the Hammond company worked at developing an electric organ that would carry its own identity as an electronic instrument. That meant, in part, emulating a range of other instruments—synthesizing a variety of sounds—as pipe organs had always done, but with qualities unique to an electronic machine. In earlier years, Hammond had been forced to confront the folly in attempting to mirror the performance of pipe organs too closely. The company had been advertising its electric organs as capable of producing “real” music that was “fine” and “beautiful,” producing “infinite tones” capturing “the entire range of tone coloring of a pipe organ.” The Federal Trade Commission, responding to complaints from the Pipe Organ Manufacturers Association, filed a charge of false and misleading advertising against the Hammond organization.

In protracted hearings on the case, the FTC adjudicated a comparison test of a $2,600 Hammond Model A electric organ and a $75,000 instrument with 6,610 pipes, built by an esteemed organ maker, E. M. Skinner, for the Rockefeller Chapel at the University of Chicago. Two juries, one of music experts and one of student volunteers, assembled in the chapel pews to hear thirty selections of music and name the instrument they thought was playing each one. The test, though not rigorously scientific, suggested that distinguishing between the two organs might not be easy for every listener.

In response, the pipe organ trade group claimed that Hammond’s people had tweaked the settings of the Skinner instrument to make it sound more like a Hammond. The FTC, in its ruling, made a compromise. It called for Hammond to cease making claims of parity between its electric products and pipe organs, but did not prohibit the company from continuing to call its music “real,” “fine,” and “beautiful.” In a rare incursion by the commission into the domain of aesthetic values and the ideology of authenticity, the FTC allowed that the output of electromechanics could be something real, and that the sounds could be fine and beautiful in ways of their own.

The Hammond company recovered well from the collapse of its Novachord adventure, refining its line of electric organs and finding them selling steadily. Its best customers were churches, particularly houses of worship in African American communities without the space to house or the means to purchase big, expensive pipe organs. The vibrantly electrical sound of the Hammond, with settings that brought a piercing bite to the chordal attack, clicked with musicians and congregations in Black churches.

By the mid-1950s, hundreds of Hammond B3 organs were selling to churches every week. The B3 became the sound of gospel music in the critical postwar period of the civil rights movement, when the Baptist church was a key mobilizing force for Black consciousness and activism. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preached with an electric organ in the background at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Rev. C. L. Franklin led his followers to gospel music played on a Hammond at New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit. Franklin’s daughter Aretha would sometimes play that organ on Sundays, and she would grow to take the fire and open emotionality of gospel music far beyond the church walls.

An impassioned new style of popular music grew directly out of Black gospel, as Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, and their peers adapted works of sacred art to secular purpose, transmuting “This Little Light of Mine” into “This Little Girl of Mine,” and “Talkin’ ’Bout Jesus” into “Talkin’ ’Bout You.” The marketers and journalists tasked with categorizing things called the music “soul,” appropriately for its ability to stir the inner presence while setting the body into motion, and the jet-age buzz and snap of the electric organ were integral to its sound. The Hammond broke categories apart, with the keyboardist Jimmy Smith recording soulful, danceable organ music for a jazz label, Blue Note, and making pop hits with albums like The Sermon!

By 1966, some fifty thousand churches in the United States had electric organs, and Shindig!, a prime-time pop music show on the ABC TV network, featured a soulful organist, Billy Preston, as a series regular showcased often in solo numbers, singing and playing a Hammond organ. Preston’s most recent album, recorded shortly before his nineteenth birthday, was a collection of funky keyboard instrumentals titled The Most Exciting Organ Ever. He had been playing organ professionally since childhood in the early 1960s, when he toured with Little Richard, after Richard had abandoned rock ’n’ roll to sing gospel music and then decided to return to rocking after all. Preston was performing with Richard in Hamburg in 1962 when he first met the Beatles.

And that, in a circuitous way, led to his being invited eventually to play organ and electric piano with the Beatles themselves. On Abbey Road, the final album they recorded, Preston played electric organ on the John Lennon track “I Want You,” though his playing is overwhelmed by the sound of the Moog IIIp synthesizer, which George Harrison had trucked from his house in Surrey to the EMI studios for the Beatles to experiment with.

All four of the Beatles noodled with the Moog in those sessions, and the synthesizer shows up conspicuously in tracks by each of them: Lennon’s “I Want You,” Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun,” Paul McCartney’s “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” and Ringo Starr’s “Octopus’s Garden.” Lennon’s idea was to use the machine to generate an insistent rush of white noise, which would grow stronger, ever louder in the mix, until it drowned out every other sound on the track. The mix the Beatles ended up using fell a bit short of that: some sounds other than the Moog noise are still discernible before the track ends up abruptly with a razor slash of the tape, but the effect of a mounting tsunami of extra-musical electronic sound came across, and there was nothing like it on any pop record of the time.

“We used the Moog synthesizer on the end [of ‘I Want You’],” Lennon said, as he was quoted in the Beatles’ Anthology book. “The machine can do all sounds and all ranges of sounds—so if you’re a dog, you could hear a lot more. It’s like a robot. George can work it a bit, but it would take you all your life to learn the variations on it.”

*

In the battle of wills between human and machine, the Moog synthesizer won the early rounds. Then came Wendy Carlos.

To make the breakthrough Moog album, the first record of music produced entirely by synthesizer to hit the Billboard charts, Carlos had to customize components and parts she special-ordered from Robert Moog and devise her own arabesque system of techniques to accommodate the technology’s abundant quirks. The project was a collection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach adapted to the Moog and performed by Carlos, released by Columbia Records late in 1968 under the title Switched-On Bach, a reference to the recording’s electronic character with a wink in the direction of drug-savvy, turned-on young people who might ordinarily not buy albums of baroque music.

Since the keyboard instruments of Bach’s time could play more than one note at a time, Carlos had to work out a way to record single tones then record over them multiple times in perfect synchronization, using an instrument that slipped out of tune easily and often. Working primarily in a studio she built in her one-room apartment in Manhattan, Carlos put more than a thousand hours into the project over five months’ time.

Her objective was, essentially, to humanize the synthesizer—in her words, “to demonstrate to the world that electronic music did not equate with a stereotypically weird and unapproachable collection of disjunct bleeps and boops lacking anything one might call musical expression and performance values.” A music scholar with a graduate degree from Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, Carlos was a high-level thinker who gave human feeling primacy in music she made by means of electronic synthesis. She prized emotional truth in this and the larger body of synthesizer work she recorded after Switched-On Bach, a few titles of which were initially released under the name she was given at birth, Walter Carlos. During the period Switched-On Bach was being made, Carlos was undergoing hormone treatments for gender dysphoria.

The revered pianist Glenn Gould, a notorious miser with praise, admired the entirety of Carlos’s achievement with Switched-On Bach. “The whole record, in fact, is one of the most startling achievements of the recording industry in this generation and certainly one of the great feats in the history of ‘keyboard’ performance,” Gould said in an interview on Canadian radio. “Theoretically, the Moog can be encouraged to imitate virtually any instrumental sound known to man, and there are moments on this disc which sound very like an organ, a double bass or a clavichord, but its most conspicuous felicity is that, except when casting gentle aspersions on more familiar baroque instrumental archetypes, the performer shuns this kind of electronic exhibitionism.”

Carlos, in an interview of her own with the same station, spoke humbly of her work and looked ahead to a time when, she predicted, synthesized music would become broadly accepted—normalized, no longer taken as a novelty. “We’re just a baby,” she said. “Although now we can see that the child is going to grow into a rather exciting adult, we’ve still got to take one step at a time. It will become assimilated. The gimmick value—thank God—is going to be lost, and true musical expression, and that alone, will result.”

Switched-On Bach was an unexpected hit, a record people seemed to need, and not just want, to satisfy their curiosity and be attuned to the increasingly electrified world. Released late in 1968, it hit the top of the Billboard classical chart in January 1969, and stayed in the number-one position for the next three years. It simultaneously crossed over to the pop charts, where it made it to number 10, in between The Association’s Greatest Hits Vol. 1 and Bayou Country by Creedence Clearwater Revival. Before the end of summer in 1969, it was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America. Within five years, it would sell more than a million copies.

The critical response was tempered, as if critics needed time to come to terms with the synthesizer and its possibilities. The presence of Bach as the source of the music appeared to help some people accept the equipment Carlos used as part of a continuity with the past, with one writer explicitly linking the Moog to historical machines—that is, the machinery of musical instruments.

“It would be easy to pass this recording off as just another gimmick of our ultra-gimmicky age,” wrote the critic Thomas Willis in the Chicago Tribune. “Who cares if expressive and musically well-informed performances of Bach can be synthesized in the laboratory? There are plenty of other machines—violins, organs, flutes, and the like—which can produce the sounds more easily and economically. Operators for these, while not as plentiful as electronics engineers, are still available.

“Tomorrow, Switched-On Bach may be a collectors’ item documenting today’s first halting steps across another bridge between science and art.”

Weird-looking and arcanely technical, an object of fascination to kit-building hobbyists and sci-fi nuts, the electronic synthesizer was generally conceived of as square, white, and male enough without being associated with music as square and white as Bach. Attitudes toward synthesizers began to shift, with Wendy Carlos helping to change the way perceptions of electronic music were gendered. Still, the synthesizer was far from being seen as the coolest, hippest thing around, until 1972.

As the preface to the story of this hard turn in attitudes toward the synthesizer, a twenty-eight-year-old audio engineer named Robert Margouleff heard Switched-On Bach when it was released, in 1968. Loosely associated with Andy Warhol’s Factory, Margouleff had been making his living in advertising work while pitching in on Warhol projects and following his idiosyncratic curiosities. (Margouleff would later be co-producer of the Warhol film Ciao! Manhattan, a vérité semi-biography of Factory “superstar” Edie Sedgwick.) After buying a Series IIIc synthesizer from Robert Moog and befriending its inventor, Margouleff set out to build a mammoth super-synthesizer that could outperform the Moog.

Working in collaboration with Malcolm Cecil, a British jazz bassist with a tech bent who had recently moved to New York, Margouleff cobbled together multiple Moog components with additional modules and several keyboards, concocting what turned out to be the largest, most advanced music synthesizer in the world, a machine capable of playing polyphonically with quasi-symphonic effects. Margouleff and Cecil called it The Original New Timbral Orchestra, or TONTO. “It’s not one instrument,” Margouleff would say. “It’s all instruments at the same time.”

The electronic synthesizer was generally conceived of as square, white, and male enough without being associated with music as square and white.

Composing, experimenting, improvising, and having fun together, Margouleff and Cecil produced an album of original synthesizer music titled Zero Time, and it was released in 1971 with the artists credited as TONTO’s Expanding Head Band, a name Margouleff thought of while tripping on peyote. The music captured that provenance: it was electronic head-trip music, spacey but melodic and oddly, unpredictably beautiful. As Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo would describe it in notes for a reissue of Zero Time on CD, “TONTO represented the cutting edge of artificial intelligence in the world of music. Robert and Malcolm [were] the mad chefs of aural cuisine with beefy tones and cheesy timbres, making brain chili for those brave enough and hungry enough.”

An American bassist friend of Margouleff’s, Ronny Blanco, was acquainted with Stevie Wonder and gave him a copy of Zero Time. On the afternoon of Saturday, May 29, 1971, early in Memorial Day weekend, Blanco showed up at the studio where Margouleff and Cecil had set up TONTO, accompanied by Wonder, who was carrying Zero Time under one arm. As Malcolm Cecil would recall, “He said, ‘I don’t believe all this was done on one instrument. Show me the instrument.’

“He was always talking about seeing,” Cecil said. “So we dragged his hands all over the instrument, and he thought he’d never be able to play it.” Within an hour, the three of them had started recording, with Wonder playing the multiple keyboards Margouleff and Cecil had set up. By Monday night, the end of the holiday weekend, Wonder, Margouleff, and Cecil had worked with the TONTO to record seventeen full tracks of new music, including all the selections that would soon appear on the album Music of My Mind.

The timing was not random. Just two weeks earlier, on May 13, 1971, Stevie Wonder had turned twenty-one, the date he had been awaiting for years to be released from his contract with Motown Records. Berry Gordy has signed the outrageously gifted Stevland Morris Judkins, in coordination with his parents, when he was just eleven years old, a minor who would remain a minor for ten more years. Gordy renamed him and was soon promoting him as Little Stevie Wonder, the 12 Year Old Genius. Working steadily at Motown, the hit factory Gordy ran on the model of the Ford assembly line, Wonder generated a string of chart-topping records made Berry’s way: “Fingertips,” “Uptight (Everything’s Alright),” “I Was Made to Love Her,” “Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours),” and more.

“I was trapped for many years,” Wonder would explain. “I’ve always felt I’ve been confined within a set style of work—that people expected a certain thing from me. Like, ‘Stevie Wonder appeals to this—this is him.’ I think a lot of artists are categorized or labeled in this way, and it’s bad. People should let you be as free as possible and up until now I really haven’t been.”

Wonder saw liberation in the synthesizer’s ability to do all the work Berry had had done by the Motown production staff. “Stevie was apparently quite taken by the idea that this was a keyboard instrument that he could possibly play that made all of these sounds,” Cecil recalled. “He was tired of having to play his songs to an arranger who would then go away and write the arrangement, record the track with the band, call Stevie in after it was recorded, tell him where he had to sing, what he had to sing, and then send him away again while they did the mix. And Stevie said it sounded nothing like what the song sounded like in his head.”

The expansive technology Margouleff and Cecil put in Wonder’s hands stirred his creative imagination and seemed acutely suited to an artist who, having lost his sight soon after birth, had a highly developed sensitivity to nuances in sound. “I didn’t know what he expected from it,” Margouleff said. “I think Stevie acted on impulse.”

Wonder was taken by the TONTO’s ability to generate unorthodox and malleable sounds that felt more like abstractions, like thoughts in aural form, than the output of a musical instrument. He found using the synthesizer to be “a way to directly express what comes from your mind,” as he told a reporter at the time. “It gives you so much of a sound in the broader sense. What you’re actually doing with an oscillator is taking a sound and shaping it into whatever form you want. Maybe a year and a half ago I couldn’t have done these kinds of tracks. I don’t know. I think your surroundings and environment have a great deal to do with what comes out of you, how you write.” Using a machine with no presets, Wonder was able to conceive and execute sounds never heard before. In fact, the early synth-tech limitations of TONTO required that he work that way.

Returning to Detroit, Wonder leveraged this new material of a whole new kind to negotiate a new contract with benefits unprecedented at Motown, including complete creative freedom to compose, perform, record, mix, master, and own all the music released under his name at a high royalty rate (reported to be between 14 and 20 percent of record income).

Beginning with the appropriately titled Music of My Mind, released in 1972, Wonder would work with the TONTO to make four albums of technically radical, openly emotive, and wholly original music, repositioning its creator as a fully mature and singular creative force. The albums included Talking Book, Innervisions, and Fulfillingness’ First Finale, with the singles “You Are the Sunshine of My Life” and “Superstition,” his first number-one hits in a decade, “Higher Ground,” “Living for the City,” “You Haven’t Done Nothin’,” and “Boogie On Reggae Woman,” among others.

On Wonder’s biting new songs of social critique, especially the grim operetta “Living for the City,” the eerie programming of the TONTO darkened the atmosphere and heightened the tension. On rhythmically propulsively songs like “Superstition” and “Higher Ground,” the piercing synth tonalities brought a dimension of unsettling mystery to Wonder’s virtuosic, churning keyboard work. The weirdness of synthesized sound found a way out of the tech lab and onto the dance floor. Your body’s grooving, and your mind is wondering, What the fuck is that sound? “I love getting into just as much weird shit as possible,” Wonder told the writer Ben Fong-Torres in an interview about his first synthesizer records for Rolling Stone. The TONTO provided him with sonorities, textures, layering options, and rhythmic possibilities as weird as musical shit could get in the 1970s. The music would stand as the high-water mark of Wonder’s career and establish him as prince of a new domain of synth-laden, Afro-futurist pop. “This collaboration [between Wonder and the creators of TONTO] changed the perspectives of Black pop music as much as the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band altered the concept of white rock,” wrote the critic John Diliberto.

As synthesizer technology progressed, Stevie Wonder would go on to compose and record fruitfully, with unabated imagination and no further need for the TONTO, although tracks he had made with it appeared on several of his later releases. At the same time, Margouleff and Cecil worked with a range of other artists of color impressed by Stevie Wonder’s work with the TONTO—Gil Scott-Heron, the Isley Brothers, Quincy Jones, Wilson Pickett, Billy Preston, Weather Report, Bobby Womack, and others—to embed the sound of the synthesizer into Black pop of the late twentieth century.

“Just look at what Stevie did with the synthesizer, and then what I did when I got my hands on it,” Quincy Jones told me. “It’s a machine for making sculpture with sound—for sculpting sound. It takes a pure electronic signal and sculpts it into something beautiful. Or it can, if you know how to work with it, like I do. Don’t you dare try to denigrate the value of technology for making music—not to me. I know better.

“The thing is, the thing is this: People didn’t expect all that innovation to come from Black musicians in the pop arena. They forgot, nobody knows how to take something that looks like it’s nothing and then prove to you that it’s really something the way a Black artist can. One thing a Black man understands is that something may look like it’s nothing, but that doesn’t mean it’s nothing. I’m talking about a man, but that’s not all I’m talking about.”

__________________________________

Reprinted from The Uncanny Muse: Music, Art, and Machines from Automata to AI by David Hajdu. Copyright © 2025 by David Hajdu. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

David Hajdu

David Hajdu is the author of seven books, including Adrianne Geffel: A Fiction, and a three-time National Book Critics Circle Award finalist. A musician and composer, he is the music critic for the Nation and a journalism professor at Columbia University. He lives in New York City.