From the Ashes of Failure: On Cary Grant, Crop Dusters, and Character Arcs

Meg Shaffer Considers How Hitchcock Needed North by Northwest to Be a Hit

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 masterpiece North by Northwest was born from the ashes of failure. Hitch needed a hit after the disappointing box office of 1958’s Vertigo. He and screenwriter Ernest Lehman were assigned to write an adaptation of the novel The Wreck of the Mary Deare. The two men worked for weeks but couldn’t find an interesting way to tell the story. Lehman tendered his resignation with apologies. Hitch didn’t accept the resignation, and their conversation went something like…

Hitch

Let’s write something else.

Lehman

I’d love to write a film

that’s the Hitchcock film to

end all Hitchcock films.

Hitch

You know, I have always wanted

to do a chase scene across the

faces of Mount Rushmore.

They gave up on adapting The Wreck of the Mary Deare entirely and went to work on a film they called They Man in Lincoln’s Nose which was eventually retitled North by Northwest. Not only a big box office hit at the time, but it also inspired the James Bond film franchise, gave Cary Grant, arguably, his best role, and the British Film Institute’s 2022 Sight & Sound poll ranked it #45 on their list of the best films of all time (Hitch’s “disappointing” Vertigo was ranked #2). All because the two creators realized they were writing a dud, called it quits, and started something new.

One reason North by Northwest succeeds is that it creates the perfect character arc for its hero. Cary Grant plays a Manhattan adman named Roger O. Thornhill. In the first scene, Roger and his secretary fast walk and fast talk from an elevator and down a busy sidewalk (Aaron Sorkin must have been a fan). They discuss meaningless sales numbers and a gift for a woman Roger’s seeing. Maggie, his secretary, begs a cab for her tired feet. With a smooth lie, Roger commandeers one for her.

ROGER

I have a sick woman here.

Would you mind terribly?

MAN

Why no… I mean–

Inside the cab, Maggie scolds Roger, telling her boss the man certainly knew he was lying. At this moment, Roger seals his cosmic fate, inviting Destiny to teach him a much-needed lesson.

ROGER

In the world of advertising

there is no such thing as a lie,

Maggie. There is only

The Expedient Exaggeration.

Already we know everything we need to know about Roger O. Thornhill. He’s handsome, charming, and will pay for a cab when his secretary is tired–all positives. But we also know he’s a fake and a liar, and he sees nothing wrong with any of that.

While at the Plaza Hotel, Roger realizes he needs to send his mother a telegram about their theater plans. Look at this, Ernest Lehman is telling the viewer, Roger’s a liar and a fake, but he’s not so bad. He loves his mother! Kind of?

But in a world where Destiny plays games but not favorites, it’s this filial act that throws Roger into the soup. A waiter happens to page a man named George Kaplan the very second Roger’s hand shoots up to summon help. Two goons with guns are looking for this Kaplan character and assume Roger is him. Roger is quickly kidnapped and whisked away to meet his doom. And James Mason.

Two opposing acts of kindness to women–one slightly wicked (cab theft), one mildly sweet (theater plans)–mark Roger as both a man in need of help and a man who deserves the assist.

And all of this happens before page ten in a 179-page screenplay. Masterful storytelling. Blink, and you’ll miss it. But don’t blink because there’s more.

Writers are taught that a character’s want is the plot and their need is the theme. In North by Northwest, Roger wants to clear his name by finding the real (though non-existent) George Kaplan, super spy, but what he needs is to become a genuine person. The way this is accomplished is another stroke of Ernest Lehman’s storytelling genius–to become real, Roger must embrace being fake. He must play George Kaplan to take on James Mason’s spy ring. He fakes his name and profession, telling double agent and love interest Eve Kendall he’s Jack Phillips, a sales manager.

After Eve betrays him, he fakes ignorance. In an auction house, he fakes insanity to get himself arrested and away from killers. Finally, he fakes his own death. Even the “O” in Roger O. Thornhill is fake (a sly dig at David O. Selznick, who Hitch did nOt like). But when he learns a government agency has deceived him and will let his true love Eve be murdered to preserve American interests, Roger has a moment of clarity. “You lied to me!” he says in anguish. Now Roger knows what it’s like to be on the other side of “The Expedient Exaggeration.”

From this scene on, Roger is no longer a fake or a liar. The glorious gray flannel suit, the uniform of the faker, is long gone. Dressed down literally and metaphorically, Roger will face certain death, fighting for his love without any armor but the truth.

But how do we get from point A–a dull life of telling lies to steal taxis–to point Z–an action-packed existence, hanging off the face of George Washington and being shot at to save Eve?

It’ll take a crop duster.

The crop duster set piece in North by Northwest is one of the most famous action sequences in the entire history of film and filmmaking. Instantly recognizable, often parodied, and still iconic, posters of the scene grace the walls of film students to this day. There is just something powerful about the sight of Cary Grant in his pristine, perfectly-tailored gray suit running for his life across barren fields as a heavily-armed biplane shoots at him from the sky.

It’s also the film in miniature–an innocent man targeted by forces beyond his comprehension. First, he runs for his life. Then he faces them and fights back, winning against impossible odds. In fiction, a brush with death symbolizes the hero’s descent into the underworld. The hero must go down to come up, must die to be reborn. Roger survives his iconic showdown with the crop duster, and from that moment on, he’s no longer on the defensive. Instead of running from the baddies, he goes after them. The fake has become a real threat. The man who began movie-life two days earlier dictating sales memos to his secretary on his way to get sloshed at The Plaza is now about to blow up a spy ring.

Sixty-three years after its release, North by Northwest remains wildly entertaining, delighting audiences and inspiring young filmmakers. But it’s also still teaching writers a thing or two about the art of writing arcs. And even if you learn nothing from the film, Cary Grant in that suit! Need I say more?

______________________

At the time of writing, the Writers Guild of America is currently striking for better pay and working conditions. Considering that director Hitchcock wanted to use a tornado to attack Cary Grant and it was screenwriter Ernest Lehman who talked him into the crop duster instead, let us remember the vital importance of writers to filmmaking.

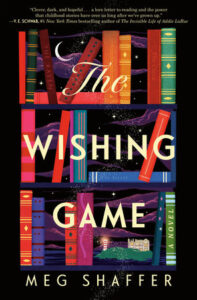

Meg Shaffer’s The Wishing Game is available now from Ballantine Books.

Meg Shaffer

Meg Shaffer is an MFA candidate in TV and Screenwriting at Stephen College. Her novel The Wishing Game (“like Charlie & the Chocolate Factory but make it books” - The Bloggess) is available on May 30th from Random House in hardcover, eBook, and audio.