From Squalor to Salon: The Amazing, Improbable Life of Emma Reyes

Daniel Alarcón Traces the Journey of a Great Colombian Artist

Every work of art—every book, every film, every painting—is an unlikely achievement. We know this instinctively, of course. The vision one has for any piece at the outset can never be more than partially fulfilled, limited as we are by our talent, our time, our ability to execute. Even so, some works of art feel more unlikely, more miraculous than others, and Emma Reyes’s remarkable epistolary memoir is one of them.

It’s best to say it plainly. The very fact that this book exists is extraordinary. Everything about it, from the author’s backstory—her childhood in grinding poverty, abandoned by her mother in the Colombian countryside, her escape from a convent, her improbable life in Europe—to the fact that she managed, without any formal education, to write these beautiful, moving letters, maintaining the correspondence across decades; then, the manuscript’s survival and eventual publication in Colombia—all of this is astonishing.

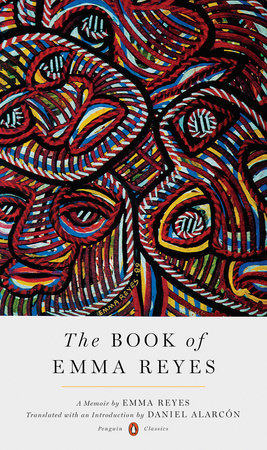

When she died in 2003, at the age of 84, Emma Reyes was known—to the extent she was known at all—primarily as a painter. She’d been living in Europe for decades, having escaped the most miserable, stultifying kind of poverty her native Colombia could offer a child, and established herself as a presence in France, a kind of godmother to Latin American artists and writers. As a painter she was a peripheral, if beloved, figure on the scene. Felipe González, editor at Laguna Libros, the independent house that published her memoir in April 2012, described those who knew Emma’s painting as “very few, and very old.” Still, over the course of her life, she was close with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo and rubbed shoulders with Alberto Moravia, Jean‐Paul Sartre, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Enrico Prampolini, and Elsa Morante. She made a life for herself in Paris, later in Bordeaux, as part of a Latin American and European cultural elite.

Emma was, by all accounts, magnetic, a great storyteller, the kind of person who could hold a room rapt. The stories she told most often had to do with her childhood. Sometime in the late 1940s, she met the Colombian historian and critic Germán Arciniegas, who, like others before him, insisted she write it all down. She protested that she found it difficult to organize her thoughts, and so Arciniegas offered a solution: tell the story of your childhood in letters, he said. Write them to me. The first of the 23 letters collected here is dated from 1969; the last from 1997. They aren’t evenly spaced; in fact, there was a gap of more than two decades. Apparently, sometime in the early 1970s, Arciniegas had Gabriel García Márquez over for dinner in Bogotá. He was so excited about Emma’s letters that he showed them to the future Nobel Prize laureate. Weeks later, Gabo telephoned Emma in Paris to tell her how much he’d enjoyed them, and she responded with fury. As she saw it, Arciniegas had betrayed their implicit agreement of confidentiality. Emma didn’t write him another letter for more than 20 years.

She must have known, though, there was something special in the work. According to editor Felipe González, Emma was proud of her writing—not because it was good, but precisely because it wasn’t, at least not in a conventional sense. “She wanted the book to be published with errors,” González told me. “She cultivated her mistakes.” Emma had no formal education to speak of; she was, in fact, illiterate until her late teens. Her grammar, punctuation, and spelling were plainly intuitive, and every sentence was hard earned, every error part of her inheritance, a reminder of the childhood she’d survived. The Colombian edition applied a light touch to the original. As a translator, I’ve tried to do the same, while silently correcting some of the more obvious errors.

None of which is to say her prose lacks sophistication. On the contrary, I don’t think I’ve read many books of such power and grace, or that pack such an emotional wallop in so short a space. Her memoir begins in a garbage dump in Bogotá, narrating moments of uncommon dignity, moving from there to the countryside and back again, describing with a poetic dispassion the sorts of trauma that would break most people. Emma, somehow, does not break. Colombia, or rather the version of the country that brought her up, the country described here, is classist, violent, provincial, prejudiced. The Catholic Church is unyielding in its cruelty, willing to pass judgment, even on little girls like Emma, no more than six or seven when she was abandoned by her mother and taken to a convent.

After escaping in her late teens, Emma fled to Buenos Aires, making her way across South America on foot, by train, by car, hitchhiking and working as a traveling saleswoman. When she arrived in the Argentine capital in 1943, she began to paint. She married in Uruguay and had a child in Paraguay in the years immediately after a disastrous war had crushed that nation’s economy. She was living in a small town outside Asunción when it was overrun by a group of armed looters. They sacked her home, and her newborn, only a few months old, was killed before her eyes.

This tragedy comes after the book concludes—and still Emma does not break. Eventually she won a scholarship to study art in Paris. Her husband abandoned her, opting not to travel with her, and so she left for Europe alone, to start a new life. She paid for her trip by offering to paint the ship as it sailed across the Atlantic. She hadn’t anticipated how difficult it would be and fell ill from the strain. On board the ship was a French doctor, who took care of her; they fell in love and eventually married. The years that followed took her to Mexico, the United States, Spain, and Israel. In Italy she drove a cab, and, so the story goes, she ran someone over in Rome, then fled the country before she could be arrested.

I find it easy to connect the dots between Emma’s memoir and her work as a painter: She has a visual artist’s eye for detail. The first image that strikes you is the figurine built from garbage, created by the children’s ingenuity, brought to life by their imagination, and finally destroyed by their lusts. And in the pages that follow are burning villages, endless rides across the barren plains, train stations that feel as lonely and terrifying as any in literature. There are towns that feel like outposts of civilization, sinister characters, cruel abandonments. The convent itself is a universe apart, with arcane rules and habits that Emma and her sister struggle to decipher. We see it all through Emma’s eyes: Her vision is acute, detailed, remorseless, and true. There is no self‐pity, only wonder, and that tone, so delicate and subtle, is perhaps the book’s greatest achievement.

At some point in the 1990s, Emma resumed her correspondence with Germán Arciniegas. Before his death in 1999, Arciniegas had his secretary type up Emma’s letters, and according to Felipe González, Emma herself corrected this manuscript before she passed away. It was shopped around, but no publishing house in Bogotá would take it.

When she died in 2003, Emma left 14 chests full of papers, one of which she gave to Arte Vivo Otero Herrera, a family foundation that had supported her work for years. Camilo Otero, the foundation’s director, went through the documents and found references to the letters. On a trip to Bogotá he contacted the Arciniegas family, who still had the letters Emma had corrected. Otero took that manuscript to Laguna Libros in early 2012.

Calling Laguna a small operation would be an exaggeration. In fact, when Camilo Otero arrived with Emma’s letters, it had only three employees. It specialized in art books, but before Emma Reyes, Laguna’s bestseller was a collection of 1920s Colombian sci‐fi. It had never had a second printing of any title in its catalog, and from a business point of view it was certainly a risk to publish a collection of letters by a dead painter whom few, if any, had ever heard of. Back then the employees of Laguna would deliver the books themselves, driving across Bogotá in Felipe González’s station wagon. When they took Emma’s published letters to stores in April 2012, González recalls that booksellers made fun of him.

But when they read the book, it all changed. Booksellers started talking about Emma Reyes. And, little by little, her memoir started to sell. The first print run of a thousand copies was sold out by September. And that was just the beginning. Against all odds, it became a runaway hit. A sixth edition has just been published.

My personal introduction to Emma Reyes was both unusual and typical of a book with such passionate fans—a stranger literally pressed it into my hands at the Bogotá Book Fair in 2014.

“You must read this,” she said. “You have to.” Now I urge the same of you.

__________________________________

From The Book of Emma Reyes by Emma Reyes, translated by Daniel Alarcon, available now from Penguin Classics. Copyright 2012 by Gabriela Arciniegas. Translation and introduction copyright 2017 by Daniel Alarcón. Feature image: “Emma Reyes,” by Alejo Vidal-Quadras, 1948.

Daniel Alarcon

Daniel Alarcon is a novelist, essayist and short story writer whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, Harper's and elsewhere.