From Servant to Sidekick: The “Black Friend,” Then and Now

Aisha Harris Reflects on Racial Representation in Popular Culture

The Best Friend, period, is also known as the foil, the sidekick, the cheerleader, the supporting (and supportive) character. Sometimes, their presence is practically inconsequential to the driving plot except as an obligation to fulfill a narrative trope, because if you’re a protagonist in a coming-of-age story, rom-com, or a buddy comedy, you absolutely must have a BFF who can thumbs-down that hideous outfit you’re considering wearing on your first date. You know they’re there, because they show up for a scene or two to offer some cheeky but real advice and words of encouragement or jokey comedic relief, but they probably won’t show up in a scene unless our hero is in it, too.

Sometimes—more often in TV shows, where there’s time to develop characters—The Best Friend has more to do. Sometimes they’ve got their own B-plotlines and occupy center stage for periods of time. We learn about their families, their quirks, their dating lives, and they influence the story line’s dramatic events. Think of most ensemble shows involving a group of BFFs (Living Single, Girlfriends, How I Met Your Mother) or any number of bildungsroman shows (Leave It to Beaver, Moesha, Lizzie McGuire).

Even then, there’s no questioning who is still the center of the overall narrative, the one whose perspective we’re supposed to align with most often. In the case of Girlfriends, for instance, it’s Joan (Tracee Ellis Ross) who’s the hub of the group. The best friends are the spokes.

Many of these characters are products of white imagination.

The Best Friend shows up in some form or another across all genres and cultures because it’s a useful storytelling device—you want another character who can complement and affirm the hero’s status as the primary focus of the narrative. But the cross-racial friendship, especially when it’s presented through a Black-white dynamic, is a very particular trope.

Inherent to that relationship is a more complicated power imbalance, not just in terms of character development but for the obvious reason that Black people have to move in this world differently from their white friends. Depending upon the era in which the story was conceived, and/or when it is set, this unevenness might be acknowledged or even serve as the central conflict. Or—and this has frequently been the case in interracial friendship stories of the last thirty-plus years or so—race doesn’t even come up, at least not explicitly.

The Black Friend as an abstract concept has existed in the public imagination for at least a couple hundred years, when pro-slavery advocates such as George Fitzhugh trotted out the baffling argument that the white Southerner was “the Negro’s friend, his only friend.” This disingenuous posit was an attempt to counter the imagery of slavery as an inherently brutal and inhumane practice by creating the perception of a benevolent, mutual partnership. (You can trace a direct line from this era right up to Donald Trump and every other modern-day white person who claims to have “Black friends” after being caught saying or doing something racist.)

From whence did The Black Friend arise? Black sidekicks have long existed in literary fiction and travelogues, often appearing as some version of the noble savage—that innocent-to-the-point-of-infantile character upon which white writers projected their curiosities, neuroses, and, occasionally, critiques of white supremacy.

Huckleberry Finn’s Jim is a quintessential early example of The Black Friend. Jim is a runaway slave who encounters the title character while he, too, is on the run. Huck’s not a fan of his guardian, Widow Douglas, or his mostly absentee alcoholic father, so he fakes his own death and escapes, and Jim forms a bond with Huck that is deeply rooted in their unequal power dynamic. Jim is unwaveringly faithful to Huck, showing unadulterated affection for and dependence on his traveling companion; at one point, when they’re reunited after being briefly separated in a fog while making their way down the Mississippi River, Jim expresses relief, claiming that his heart “mos’ broke” and he “didn’t k’yer no mo’ what become er me en de raft.”

Much of Huckleberry Finn is an exercise in white awakening, to some extent. Huck is reluctantly sympathetic to Jim’s plight, casually referring to him as a n——— (one of the primary reasons Mark Twain’s story is frequently among the most banned books in schools) and chastising himself for aiding in Jim’s escape. (“People would call me a low-down abolitionist,” Huck notes, while admitting he’s going to do it anyway.) As Huck wrestles with the expectations and social mores of his race, he evolves, somewhat, over the course of the novel to become even more defiant in the face of white supremacy.

Yet that obstinance arguably stems as much—if not more so—from his personality as a petulant fourteen-year-old determined to stick it to The Man as it does an acknowledgment of Jim’s humanity. Huck never sways from viewing Jim as inferior. He begrudgingly concedes that Jim might care for and love his own family in the same way “white folks does for their’n.”

And Twain’s ludicrous third act sees Tom Sawyer and Huck going through deliberately obtuse and round-the-way machinations to make their act of freeing the newly recaptured Jim more “honorable” (and more exciting) instead of just… sneaking him out the easy way. Jim is the catalyst for the protagonist’s heroism and maturity. As Toni Morrison notes in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, “there is no way, given the confines of the novel, for Huck to mature into a moral human being in America without Jim.”

Other earlier fictional Black Friends include Delilah and Annie in the 1934 and 1959 versions of Imitation of Life, who blur the line between employee and close confidante of the white protagonists; Mammy in Gone with the Wind, who strikes up an amiable rapport with Rhett Butler (he gifts her a red silk petticoat—what a guy!); and Rochester, the valet and sidekick on The Jack Benny Show.

I use the term “friend” here loosely and broadly, because many of these characters are products of white imagination, and it’s fairly common for a white imagination to see a “friendship” where a Black person might see “a relationship I need to maintain in order to feed my family/not get killed/just live relatively peacefully.”

But without them, you wouldn’t have The Black Friend in its current iterations of the last thirty-ish years, unmistakable products of their predecessors that occasionally nod toward enlightenment or at least self-awareness. And within this trope are three key ways these friends function relative to their white counterparts:

1. To give

2. To side-eye, sweetly

3. To provide purpose

Let’s return for a moment to poor Katie in She’s All That. She devotes all her time to trying to help Taylor win prom queen, so much so she forgets what it’s like to do things she actually wants to do for herself. Katie is The Black Friend of the Mean Girl, which is on a lower tier than The Black Friend of the resident-pretty-protagonist-behind-the-glasses, Laney.

Casting Black performers in the friend role was a way to demonstrate “progress” while keeping the leading roles white.

Katie is what I’d call the quintessential “Giver” for most of the movie. Every conversation with Taylor is about Taylor (prepping her prom speech, dumping Zack, dating the wild and creepy older guy).

The Giver is the best friend who gives their all but doesn’t seem to receive any of that same energy back. IRL, it’s a fairly common friendship predicament that knows no racial bounds. But why does it just seem as though Black Friends have traditionally fallen into this role so frequently in pop culture? The more obvious and cynical read on this is that Hollywood has needed to transfer the stock types of maids, butlers, and other service workers (paid and unpaid) to the more palatable, generic roles of “friend” in order to keep up with the changing times and not openly offend Black audiences. (Unless, of course, it’s a period piece set firmly in the past, which is how we’ve gotten Driving Miss Daisy and its demon baby Green Book born nearly thirty years later.)

It also seems likely that the behind-the-scenes push for greater and better representation that’s always existed—to varying degrees of success and failure at any given time—has something to do with it. The predominantly white and male gatekeepers in the industry were never going to make space so readily for more than a very select handful of Black superstars and protagonists at a time.

One way to slot in “diversity” in the least disruptive way possible since as far back as the silent movie era has been to cast Black people in sidekick roles. A study presented in 1989 looked at a small sample size of hours of network TV, spread out across four months in 1987, and found that “nearly 40 percent of television’s minorities have no contact with whites.” When interactions did occur, it was common for minority child and teen characters to socialize in “positive” ways with their white peers outside of school settings. (On shows where adults of different races interacted with one another, they found it was usually in a professional setting, where mingling is more or less involuntary.)

So what you get in pop culture is a hybrid of tropes: The Best Friend meets The Maid/Butler. Casting Black performers in the friend role was a way to demonstrate “progress” while keeping the leading roles white, an especially fruitful tactic in products targeted at kids/tweens, like the role of Lavender in the movie adaptation of Matilda. Instead of giving because they are employed (or enslaved) to do so, they are giving because…that’s what friends are for, right?

__________________________________

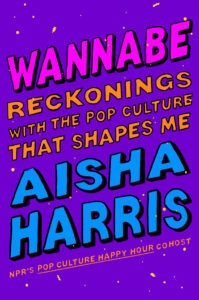

Excerpted from Wannabe: Reckonings with the Pop Culture That Shapes Me by Aisha Harris. Copyright © 2023. Available from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Aisha Harris

Aisha Harris is a cohost and reporter for the hit NPR podcast Pop Culture Happy Hour. She previously held editorial positions at Slate and the New York Times. Aisha earned her bachelor’s degree in theatre from Northwestern University and her master’s degree in cinema studies from NYU.