From Memoir to Fiction: A World More Beautiful and Real than Reality

Yara Zgheib on Blending the Real With the Imaginary

Lisa Robertson starts one of her novels with the words: “These things happened, but not as described.” I feel that should be a disclaimer before every single one of mine.

I write fiction, which is to say what I write isn’t real, not really. I have written and published two novels and am (allegedly) hard at work on my third.

But I feel like a fraud. I cannot write fiction; I do not know how. Everything I ever wrote was true, even if it never happened.

The Girls at 17 Swann Street, my first novel, is the story of Anna, a young woman with anorexia who is admitted into a treatment center for girls with severe eating disorders. The book opens on the day Anna is checked into her room, with her inner voice: “I call it the Van Gogh room.” I know that room because those were my thoughts; I was the girl in that treatment center, and I wrote those thoughts in my journal.

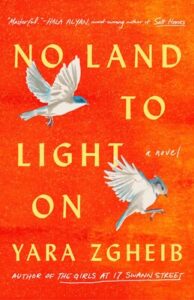

Everything I ever wrote was true, even if it never happened.My second novel, No Land to Light On, also began in my journal after a random executive order suspended my husband’s immigrant visa to the US, preventing him from coming home to me and our children after a trip abroad. We both lost our visas—and our jobs, home, savings, and lives in the US as we were forced to leave the country indefinitely. In one scene from the book, the character Sama tries to cram a life into a suitcase, into “twenty-three kilograms.” That sensation, in her chest—I know exactly how she felt.

These books were never meant to be novels, or even meant to be book—not at first. At first, they were tools for survival; a way for me to breathe in the world. It is a difficult world to breathe in, this one—it hurts, it’s broken, it’s angry and unfair and doesn’t make sense. It is full of walls. It is nothing like the worlds in fiction, which are so many and all possible. That is why I read, incidentally; another tool for survival and escape, to imagine, just for the span of a story, a world in which breathing is easy.

In good fiction, the best fiction, when you close that book, you keep imagining that world. You believe it. But I wasn’t going for that when I wrote my first, second, fifth manuscripts of either of my books (all of which were rejected). I was writing to tell the truth about real things. I was writing nonfiction.

I had nothing against fiction. I love fiction. I cannot remember a time without stories (though I can remember times without friends). I read during recess at the Jesus and Mary elementary school playground, on the stone bench under the oleander tree; stories took me away from the taunting and bullying and gossiping to a beautiful place. I knew, even then, that fiction was a way of escaping the world.

My own story was just a vehicle; it was all I had. Except no one wanted to publish it.But I also wanted to change it, or at least make it a little better. I thought if I could write something true and beautiful, that could touch somebody, someone I do not know and would never meet, far away, in a different place or even time, something they would understand and that would make them feel understood, or even just smile or breathe out, a little easier, like I am doing now, that would be changing the world. A little. But, in order to do that, it had to be true. So, I wrote nonfiction.

It didn’t have to be a memoir. It wasn’t about me. It was about the experiences, the feelings we all have; the desire for love, belonging. My own story was just a vehicle; it was all I had. Except no one wanted to publish it.

My story lacked action. It lacked big scenes of conflict, love, revelation. Real life is quieter, mine at least. I do not run away from treatment centers and confront immigration officers. I was told, over and over, by wonderful, well-meaning, very smart editors across the publishing world, who sell books for a living, that mine wouldn’t. My story needed tension, a villain the reader could hate, a hero they would want to follow to the end of the earth—or treatment, or the airport tarmac. Most of all, it needed resolution.

My endings were ambiguous, because life is. They didn’t make sense, because life doesn’t. Publishers asked for a happy ending, but I couldn’t give it. I didn’t know if the ending would be happy. I hadn’t reached it. And I wasn’t a hero….

I write novels…to imagine a way of being, and of breathing easier, in this world; to imagine it, maybe, as more beautiful and more real than reality itself.Then an editor asked: What if you were?

What? A hero? What if…I could change the world? At least in the story I was writing. Wasn’t it my story? If it really wasn’t about me, if it was about love, courage, belonging, couldn’t it be fiction? If it were….

My mind exploded with possibilities. If it were fiction, Swann Street could be about anyone who has ever struggled with an eating disorder or loved someone who has. It could be about anorexia, yes, but also about friendship, courage, love, about what beauty really means. Anna could get out of that center, could get better, not miraculously—she would still have her struggles, as we all do—but she would have a chance at life, and maybe someone reading her story would glimpse something in her world that they recognize, something hopeful.

If it were fiction, No Land to Light On could be about anybody whose life was changed by forces outside their control. It could be about a different executive order, about any executive order; about Lebanon, Syria, Ukraine, Afghanistan; about scholarship students and refugees, about anyone who ever left their country, by force or by choice; anyone who left home, searched for home, struggled with what that word means. It would still be true; both novels are still true. They are about what I believe: that the right way is good, that the right way is forward, and that the journey, life, really, is beautiful.

In a magnificent piece in The Paris Review, Eloghosa Osunde writes:

In the world that I dream of, it’s easy to move about. It’s easy to walk home at night with a bag of Skittles. It’s easy to relax in your own house. It’s easy to resolve conflict. It’s easy to hang out on the street. It’s easy to do the work you want to do. It’s easy to come together. It’s easy to have sex, to seek pleasure and joy, to wear what feels right. It’s easy to be soft. It’s easy to remember your power. To be in public. To use. It’s easy to not have to work. It’s easy to be in bed all day. It’s easy to be free. It’s easy to be alive.

That is why I write novels. Not to change the world; I cannot. Not to invent another; I do not know how. But to imagine a way of being, and of breathing easier, in this world; to imagine it, maybe, as more beautiful and more real than reality itself.

__________________________________

No Light to Land On by Yara Zgheib is available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.