From Fact-Checking to Fiction: On the Multifaceted and Often Fruitless Pursuit of Truth

Austin Kelley Considers the Evolving Role of Fact-Checkers in an Era of Endless Lies

When I was a young, confused graduate student, I became a fact checker. I was tired of not-writing my dissertation and wanted to do something more useful, more literary. I found work as a copy editor with a bit of fact checking thrown in.

The magazine was not exactly literary, but it might have been useful. It was Mother Earth News, which still exists, a compendium for back-to-the-landers and seed bankers, and I checked facts about solar panels and acorns. It’s tempting to think those were simpler times. There were no fact-checking websites or fact-checking robots. No lying robots, either. Or not that I knew of. Instead, I was looking up information in books: Yes, squirrels sometimes dig holes and don’t put any acorns in them, but then fill them back up to trick acorn thieves.

I bounced around as a freelance checker after that: Spin, Vogue, Teen Vogue! For a few years, I checked at The New Yorker which was sort of like joining the Yankees of fact-checking. There, fact checking is actually prestigious. When you call a source, they answer! Sometimes they are nervous. And the checking department is big: a whole team of nerdy skeptics like me pick apart each article and then put it back together before it goes to press. They even check poetry and cartoons (For a while, I was in charge of both). This picking apart includes basic questions: Is Nicki Minaj spelled correctly? (Check.) Is “full fathoms five” really 30 feet deep? (Check.) Do whales have whiskers? (Sort of. Some have hair follicles that, scientists suspect, they use as a sense organ).

I liked all the weirdly obsessive questioning. It felt occasionally useful, and even literary.

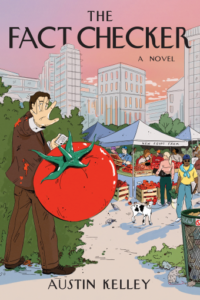

I liked all the weirdly obsessive questioning. It felt occasionally useful, and even literary. In my novel The Fact Checker, I pulled a few examples from my real experience. Once, while I was on the phone with Shaquille O’Neal’s girlfriend, I had her strip off his shirt in order to confirm the spelling of a tattoo near his belly button (“LIL Warrior”—No apostrophes). Another time, when I asked Tony Curtis about the cat he named after his ex-girlfriend Marilyn Monroe, he described their sexual relationship—in much more detail than I needed.

Checking, of course, isn’t all bedroom talk. Nor is it all concerned with “facts.” I wonder if this is why longtime fact checkers often drop the “fact” from their title and just call themselves “checkers.” Their purview is broader than facticity. They check logic; they check fairness. How much evidence do we have for a claim? What objections might someone raise? What’s worth saying in print? Checkers will tweak the tiniest things to ensure that the story is carefully wrought and truer. They will sometimes add a “may” or a “perhaps” into a sentence just to inject a bit of doubt. Once upon a time, I thought that readers were attuned to the shades of nuance that mays and the perhapses lend to a statement. These days, I’m not so sure.

But every one of those mays was backed by a lot of work. One of my favorite things about checking was the use of colored pencils. For a particularly complex story a checker might underline all the passages that came from a key source—let’s say a government leaker—in red, all the background facts in blue, quotes from other sources in green, and so on. Some sentences might be underlined in multiple colors because they came from multiple sources, or because the checker wants to make sure to double or triple check a key idea.

Fact checking is certainly no guarantor of fairness and no panacea.

At The New Yorker, before going to press, we printed out galleys with a single narrow column of text running down the middle of the page and a ton of blank space on each margin for comments and queries and suggested edits. A well-checked proof was a colorful map of the deconstruction and reconstruction of a story. And then right before a story went to press, the fact checker, the editor, the writer, and the head copy editor would get together and assess the story page by page, talking out any final concerns they might have. At its best, this was a model for good thinking—multiple people trying to inhabit multiple perspectives to make a story about the world a better, truer, and more just story.

Such closing meetings, even if they inspired debate, required a shared ethos. That’s one of the reasons that fact checking of politicians throws me. Though it shares a name, it is an entirely different beast—one that pits the checker against a politician’s word, not working with it. I can’t read the fact checking of Trump. Checkers point out his outrageous lies, and then spill even more ink showing how many of his claims are “misleading.” I understand the impulse: the checkers are working under the same premise they do when checking a journalist. They want to do more than correct information; they want to correct faulty logic and bad thinking. But the well of bad thinking is deep. Trump is factually wrong and also deeply wrong. He doesn’t care for evidence—or other people. I’m not sure fact checkers, low-ranking nitpickers, can help.

I’m always wary, in fact, of the kind of people who think fact checking is some messianic practice, or that all we need to do is reveal the truth and justice will follow. This reminds me of those think-tanky technocrats who assume that if we let the experts fix the systems, all will be right. There’s no need for politicking, persuasion, and community-building. There’s no need for debating what we value, and how to value it best and how to manifest those values in the face of the facts before us. Fact checking is certainly no guarantor of fairness and no panacea. In my novel, fact checking actually becomes a pathology. The narrator is so obsessed with finding some hidden truth that he goes rogue and loses his shit. Maybe this is a condition we all face—in a world that is increasingly a morass of complicated and predatory lies.

“Increasingly?” Can we fact check that? The Fact Checker is set in 2004 before Truth Social or Meta but those were also the days of WMDs and Known Unknowns. Part of the reason I set the novel in that era is because it felt like the beginning of an unraveling. I imagine, though, that McCarthyism felt like that too, and the Spanish American War, and before. There’s no golden age of truth. Still, I can’t imagine being a checker today. It must feel like sticking your finger in a dike while an ocean of lying algorithms and evil billionaires bears down on you. On the bright side, the kid who stuck his finger in the dike did end up saving the whole town. That’s at least how the story goes—a story embedded within a work of fiction, Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates, an 1865 novel by American magazine editor Mary Mapes Dodge—and fiction is always more compelling than fact.

__________________________________

The Fact Checker by Austin Kelley is available from Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

Austin Kelley

Austin Kelley is a former New Yorker fact checker. As a journalist he has written for The New York Times, The Nation, Slate, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker. He has a Ph.D. from Duke University, and now teaches writing at NYU. The Fact Checker is his first novel.