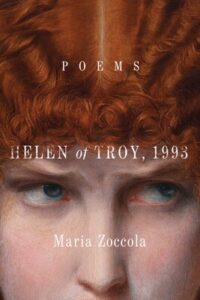

From Ancient Troy to 1990s Tennessee: Maria Zoccola on Creating an Afterlife For Homer’s Helen

“We’re raising eidolons, real and not-real, tales that move and breathe and stand side by side, speaking Troy into the future.”

Because I grew up a quiet, book-eating girl with unrestricted access to several branches of Memphis Public Libraries, I was well-versed in Greek and Roman myth long before ninth-grade English with Mrs. Bell. That was the year of Edith Hamilton and Robert Fagles, a whole class of fourteen-year-old girls punching through both the Iliad and the Odyssey in about six weeks. I already knew my gods and monsters, my heroes, my lineages. I’d been dutifully translating my way through the Cambridge Latin Course textbooks since seventh grade. I thought I was ready. But how could I have been? I was young, raw, and anchorless: easy prey for a carnivorous story looking for its next meal, and the Trojan War has a bottomless appetite. I fell into its mouth that breakneck year, and it’s been carrying me around ever since.

The Trojan War is the sticky center of a spiderweb so large its edges reach back into the beginnings of Greek myth and forward into the rise and reign of Rome. The gist of the story is this: The Trojan prince Paris awards the goddess of love Aphrodite top prize in a beauty contest among her peers, and as payment for this favor, she promises him the most beautiful woman in the world as his wife—Helen, a half-mortal child of Zeus. The problem being, of course, that Helen is already married to Menelaus, the Greek king of Sparta. Paris arrives in Sparta as a guest and abducts Helen (or perhaps they run away together—accounts vary), and Menelaus rallies the other kings and heroes of Greece to sail for Troy and take her back.

The result is a ten-year war surrounding the walled city, “hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls, / great fighters’ souls…their bodies carrion, / feasts for the dogs and birds,” an avalanche of butchery that ends with the annihilation of Troy. It’s a story about honor and fate, about how easy it is to kill and die. Ancient Greek and Roman audiences were steeped in Troy’s tangle of legends, and even modern readers generally understand the basic plot. This familiarity makes the story one of the world’s perfect tragedies: We enter the war with our hearts already broken for Greeks and Trojans alike, knowing that Patroclus will die, Hector will die, Achilles will die, little baby Astyanax will die. Knowing that all the women of Troy will soon be dragged down to the beach to join Briseis and the other captured war prizes: raped, enslaved, divvied up among the victors. Well, all the women except Helen.

Helen had a story to tell, and all I had to do was keep writing until she’d said her piece.

No, not Helen. She walks out of the ruins of Troy and returns to the throne of Sparta beside her former husband, Menelaus. The women who surround her—elderly Hecuba, prophetic Cassandra, the perfect princess Andromache—all suffer unimaginable fates, ending their stories slain or enslaved. But Helen simply goes home, as if the past decade were just a bad dream. Maddening Helen! Helen for whom the war was started. Helen in whose name a generation of men fought and died.

Euripides’s tragic play The Trojan Women is one long wail of grief, wherein Hecuba tries in vain to convince Menelaus to enact justice upon Helen for all her sins: for leaving her first husband, for refusing to leave her second even while Hecuba’s many sons perished in payment, for her “opulent appetites” that make her “hell for cities, burning hell for homes.” In the eyes of Troy and Greece alike, Helen is the war, the embodiment of their suffering. Legend says Menelaus very nearly did choose vengeance, chasing Helen through Troy with a drawn sword. But one glimpse of her otherworldly beauty at the crucial moment stopped his blade, and there was nothing left to do but to bring his slippery bride back across the sea.

I’ve always struggled with Helen, even while studying classics back in college. I often think about the 1888 painting Helen at the Scaean Gate by the French symbolist Gustave Moreau, in which a Helen of monstrous size stands before the smoking walls of Troy. At her feet lie crushed and spattered the bloody remains of those caught up in her wake: death-dealing Helen, the demigod daughter of Zeus, never truly brought to account.

But is this the best interpretation of Helen’s role in the war? After all, did Helen leave Sparta willingly, absconding in the night with her lover, cheering on the Trojans as they beat back the Greeks come to drag her home? Or was she abducted by Paris and kept prisoner behind the walls for ten long years while she wept for her former life? Or should we best understand Helen as nothing more than the pawn of Aphrodite, a doll handed to Paris as payment for a victory in a contest among Olympians? Or is Helen something else entirely, a mercurial, half-human entity loyal only to herself, the freest agent in the entire Trojan War because she is the only one not bound by honor? Helen is complicated. She defies easy answers and easy scholarship. The doomed women around her are certainly much more sympathetic figures, and it can be tempting to leave Helen well enough alone.

I myself certainly left her alone. Back in 2020, as the world ended, I was once again living inside the Iliad. The world was also ending inside the Iliad, of course, so the plains and beaches were less of a departure from and more of a simple transmutation of my own community’s circumstances. I sat out on my porch with Rocky the dog in the hours between increasingly dire Zoom calls, breathing in the dense Southern humidity of Coastal Georgia and writing persona poems in the voices of women from the Trojan War.

It was a vaguely therapeutic project, allowing the pandemic pressure valve to release through old agonies from Bronze Age Greece, hurts that belonged to Andromache, Cassandra, Helen’s sister Clytemnestra, and Clytemnestra’s poor daughter Iphigenia, who was sacrificed to the goddess Artemis by her father for wind to launch the fleet of ships toward Troy. Helen’s name lurked beneath the whole endeavor, untouched. I wasn’t sure what to do with her. I wasn’t sure I wanted to do anything with her. For a full year, I ignored her while I published or shelved the other poems from the project and started on new work with different themes. I changed jobs, moved home to Tennessee, bought a house. And in the summer of 2021, in a kind of manic daze, I suddenly dove for my notebook and wrote seven Helen poems in a row.

Our Helen is still unique, set apart, special—but not special enough to watch the tide of history turn on the axis of her body.

But the voice that emerged had nothing to do with Bronze Age Greece. It was too familiar for that, too much like a woman I might have run into one day at the grocery store or the bank. The sun began to rise over a landscape I recognized, illuminating the world of my childhood in 1990s Tennessee: station wagons and backyard barbecues and Friday-night football and neighbors who look at you sideways in church. This stifled, hilarious, cliff-edge housewife marched onto the page and introduced herself as Helen of Troy. She brought the whole gang with her, the full cast of my beloved mythos, to walk around a town that had certainly never seen their like.

Helen had a story to tell, and all I had to do was keep writing until she’d said her piece. I hadn’t wanted much to do with Helen; now I couldn’t look away. The Helen of myth might always be a question mark, but this Tennessee girl was an exclamation point. She was an imperfect mother and wife, an imperfect woman grasping for agency in imperfect ways, tangled inextricably in the plot threads of the Trojan War. Mythology hands Helen’s agency to Aphrodite, who gives her away, to Paris, who steals her away, and to Menelaus, who scoops her away from the wreckage of Troy and sails her back to her former throne. In 1993, though, her story was old, but her decisions were new—and were, inarguably, her own.

In the Sparta of myth, Helen’s departure set off a long and grinding war, shipfuls of men launched across the water to snatch back a woman of stained reputation. Before Helen’s father gave her in marriage to one among the host of lords competing for her hand, he took Odysseus’s advice to require that every man swear an oath to fight for the chosen husband if someone ever stole Helen away. No sooner had Paris spirited Helen out of Sparta than Menelaus cashed in on that promise, forcing every former suitor to raise their levies for war. But there is no war brewing in Sparta, Tennessee, no “vast armada gathered, moored at Aulis, / freighted with slaughter bound for Priam’s Troy.” Instead, this Tennessee town holds nothing more than an abandoned, powerless husband with no oath to call in, no army to revenge his humiliation. All he has is his injured pride, a wound that sickens, turns inward, curdles him into frustrated inaction. It is winter for Menelaus when Helen leaves—and winter, too, for Helen, having left.

For Helen, this deep freeze begins in Sparta and does not break, to her surprise, past the borders of her former life. How to understand Helen of Troy in 1993, choosing to go, and once gone, choosing to come home? Is she happy? Or is she just as miserable as she was before the affair? Does she even quite know the answer herself? Is happiness, in the end, even a useful metric with which to measure Helen’s life? Our Helen is still unique, set apart, special—but not special enough to watch the tide of history turn on the axis of her body. Instead, she must turn herself, and allow history to fall around her like snow.

The legend of the Trojan War has been told and retold for more than three thousand years. Permutations, additions, side stories, and revisionist histories abound in every era. Statius, Ovid, and Virgil added their contributions; so did Chaucer and Berlioz and Xena: Warrior Princess. Even in the ancient world, a counter-legend sprang up asserting that Helen never went to Troy at all. Instead, she waited out the war blamelessly in Egypt while a ghostly clone, an eidolon, went to Troy in her place (this “ghost-helen” makes an appearance in “and another thing about the affair”).

The events and personalities of the Trojan War are not matters of historical record we can track in the same way we can, for example, Churchill on the eve of World War II. Nevertheless, historians generally agree that Troy was a city in modern-day Hisarlik, Türkiye, destroyed many times through the ages, and that whichever of its destructions corresponded with the Trojan War of legend likely had little to do with a tussle over the most beautiful woman in the world. In the absence of facts, all we have are stories, each a new thread woven into a tapestry that was not finished with the fall of Troy or the fall of Rome, that isn’t complete today and won’t be tomorrow, either. All of us who sharpen our pencils and turn again to the page with these characters are writing into that long tradition. We’re raising eidolons, real and not-real, tales that move and breathe and stand side by side, speaking Troy into the future.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Helen of Troy, 1993 by Maria Zoccola. Copyright © 2025 by Maria Zoccola. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Maria Zoccola

Maria Zoccola is a poet and educator from Memphis, Tennessee. She has writing degrees from Emory University and Falmouth University and has spent several years leading creative writing workshops for middle and high school youth. Maria’s work has previously appeared in Ploughshares, The Kenyon Review, The Iowa Review, The Sewanee Review, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere, and has received a special mention for the Pushcart Prize. Helen of Troy, 1993 is her debut poetry collection.