From a Toxic Set of Norms: Maureen Ryan on Why We Ought to Burn It Down

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

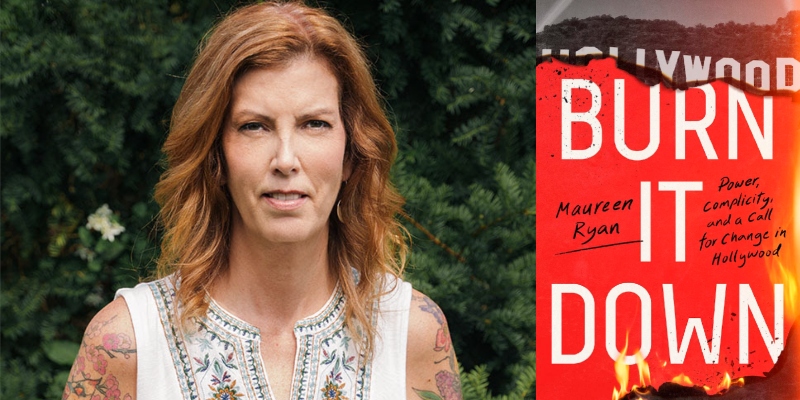

This week on The Maris Review, Maureen Ryan joins Maris Kreizman to discuss Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood, out now from Mariner Books.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

From the episode:

Maris Kreizman: I think the next layer after the conversations we started to have around #MeToo is thinking about, okay, if we’re trying to get the most egregious sex criminals out of places where they can harm people, what else might there be?

Maureen Ryan: Right. And I think, again, you’re just speaking exactly to the heart of what drove me to write this book. I was texting a friend this, sort of like the burn it down, ranting kind of thing. And I looked at those texts and then I texted my friend, and I said, I think this is a book proposal. Because a couple of years ago, I began to get this sense that people thought, well, we did it. You know, we nailed the sex pest stuff. So good job everybody.

And I just was like, what? No, what are we talking about here? If the bar to clear was like, some serial sexual assaulters were removed from some situations for a while, and maybe one high profile one went to the slammer. Given the prevalence of misconduct in this industry, that’s not nearly enough. And part of it was driven by something that other people have heard, and I certainly have heard, and I put this in the book. When you talk to people and they say, or their reps or their PR or their lawyers say, but he wasn’t a Weinstein. I’m like, okay.

MK: The bar is so very, very low.

MR: So if we’re saying a criminal, well he wasn’t Ted Bundy, okay. But also there can be other things that are bad that are not a multi-state crime spree murderer thing.

MK: And that’s why I love that you get into the story of Scott Rudin so early in the book, because it’s a really great counterpoint to the kind of Harvey Weinstein story that we’re used to. And his victims, of course, were never A-list actresses.

MR: It was truly frightening to me to delve into all the Scott Rudin profiles that I’ve done over the years. And by the way, I hope in the book I make it clear I don’t view myself as aside from and apart from the veneration of norms and even people that were problematic. I think I was very much part of that.

But there was this reflexive move in all of this coverage of Scott Rudin for years and years that was glamorizing that. And I’ll tell you a story for free that’s not in the book. I once had an off the record lunch with an executive, a really good guy. And part of the reason we had the lunch was because he worked for Rudin at one point and you wanna hear the horror stories. It’s like meeting someone who grew up in a cult or something… You wanna know what’s the dirt?

And so I wanted the dirt and I realized that I understand the reason for that interest, but there was so much veneration of this kind of behavior. And how many movies have we all watched where even from like the thirties and the forties, um, the fifties and beyond, the producer is always this guy chomping on a cigar screaming at others, chasing the secretary around the desk and that’s funny. Ha ha.

So there was a very kind of smart and subtle, overt, covert series of methodologies by which Scott Rudin or Rudin behavior was a part of the founding mythology, the bedrock mythology of Hollywood that, well, unless you scream at people and make them feel small and replaceable and worthless, then you cannot make a motion picture or a TV show.

It’s funny because there’s kind of that tradition in journalism too. Like this, the editor who comes into the city room and screams at people. And I’ve been around people like that and I’m like, why? It so rarely makes anything better.

MK: I definitely feel like that’s the case in the book world too. A similarity that I find really trenchant is that most people go into these jobs knowing that they will encounter abuse and that it’s good for them, that it will build a thick skin or that it will prove to the world that they belong in this creative industry. Seems like that’s a great thing to stop doing.

MR: A really useful paradigm for me that I use as a framework throughout the book is to imagine how an abuser has many strategies by which they keep people locked in a cycle of abuse: gaslight them, isolate them, make them think it’s good for them, make them completely revolve around the abuser’s needs and wants and violating anything that they don’t want is this massive crisis. So you slowly but surely radically change how everyone around that abuser operates and then everyone is in this very sick system.

I think if you just take that and make Hollywood the abuser, that’s really what it is. There are a lot of abusive dynamics baked in and I have to be very careful in how I talk about this stuff because some people I really care about are wonderful people and have fought the good fight to have it not be like that. But unfortunately this industry somehow successfully and very smartly implanted in our minds the idea that this is a better group of humans. This is a more enlightened group of humans because they’re in pursuit of illuminating the human condition. They care about art, they care about storytelling, they care about creativity. All these things that we culturally venerate.

But the commercial Hollywood industry that we venerate for those reasons, is it better than Amazon warehouses? Is it better than a fast food job? Is it better than Uber or, you know, I would argue, you know, if my child were to go get a job as a checker in a grocery store, they would be less likely to encounter abuse than if he went to work as an assistant for a Hollywood producer today. And that’s really sad. I really hope to hold a lot of space for the people that are doing the good work and trying to change things.

But it’s from a toxic set of norms. And that toxic set of norms is exactly what you just said. That if you are not willing to put up with inappropriate behavior, misconduct, abuse, psychological abuse, vindictive behavior that could end your career any moment, you just don’t have what it takes.

And that’s crazy. I’m really glad that you brought up publishing. Now I have a little bit more of a window into that for part of this book writing process. The HarperCollins Union was on strike, and that’s a strike I fully supported. I am glad that they achieved their goals and their goals were so modest.

MK: They’re so modest. And that’s what you say in the book too about how the Hollywood assistants are putting up with all of this stuff on top of the fact that they’re not making much money. They often have to have a second job. They work extreme hours. Many of them have to be available at all times. And it’s like, what are we doing here? Are you saving people’s lives?

MR: Exactly, and that’s, you know, it was really important to me to write about someone like Kevin Graham-Caso, to write about people who have left the industry. Kevin, you know, unfortunately is no longer with us. And I spoke to his brother and if I’m honest, what I am hoping to do is make people understand that it’s not just that we’re venerating people who have harmed, damaged and bullied and abused others in a multitude of ways. You know, criminally and just morally. We’ve driven out people who could be a force for good, you know, and some people who are forces for good have hung in there. But as you say, it’s at a cost. I cannot, I literally cannot think of one person who has not had a terrible work situation, if not multiple terrible situations.

Because, and again, I, I actually think, I think this applies across a lot of creative industries, fashion, architecture, photography, whatever influencing is. But like anything where there’s a high degree of gatekeeping, it’s very hard to make a living that’s perceived as creative. Music. When you have a very, very tiny elite tier of people who could end your aspirations on a whim because you did not get them the proper kind of soy latte, that isn’t great.

*

Recommended Reading:

The Survivalists by Kashana Cauley • The Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells

__________________________________

Maureen Ryan is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and has covered the entertainment industry as a critic and reporter for three decades. She has written for Entertainment Weekly, the New York Times, Salon, GQ, Vulture, the Chicago Tribune, and more. Prior to joining Vanity Fair, Ryan served as the chief television critic for Variety and the Huffington Post. Her new book is called Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood.

The Maris Review

A casual yet intimate weekly conversation with some of the most masterful writers of today, The Maris Review delves deep into a guest’s most recent work and highlights the works of other authors they love.