Set in a Lower East Side tenement in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns, Fourteen Days is an irresistibly propulsive collaborative novel from the Authors Guild, with an unusual twist: each character in this diverse, eccentric cast of New York neighbors has been secretly written by a different, major literary voice—Charlie Jane Anders, Margaret Atwood, Joseph Cassara, Jennine Capó Crucet, Angie Cruz, Pat Cummings, Sylvia Day, Emma Donoghue, Dave Eggers, Diana Gabaldon, Tess Gerritsen, John Grisham, Maria Hinojosa, Mira Jacob, Erica Jong, CJ Lyons, Celeste Ng, Tommy Orange, Mary Pope Osborne, Douglas Preston, Alice Randall, Ishmael Reed, Roxana Robinson, Nelly Rosario, James Shapiro, Hampton Sides, R.L. Stine, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Monique Truong, Scott Turow, Luis Alberto Urrea, Rachel Vail, Weike Wang, Caroline Randall Williams, De’Shawn Charles Winslow, and Meg Wolitzer.

*

“Well, my mom is ABC and so am I, but Ah Poh was born in this tiny little village in Guangdong. I’ve never been there, but she showed me a picture once—a little gray stone house in the middle of nowhere, just rice paddies all around. My gung gung used to catch fish in the river for dinner. They came over just before the war to San Francisco and settled in the Sunset District, and they never went back. I don’t even know if that little house is still standing, or if it got destroyed in the Revolution, or what—a lot of stuff was.

“Anyway, just after I was born, my gung gung died and my poh poh moved in with our family, and she took care of me and my sisters while our parents were at work. She used to let us play with the jade bracelet on her wrist; she’d worn it since she was a little girl, and it was still tiny, but her wrist had grown and it wouldn’t come off anymore. My mom had one just like it; it used to get all soapy when she washed the dishes and covered in potting soil when she worked in the garden. Ah Poh gave one to each of us girls when we were little, tried to get us to wear them, too, but I couldn’t stand the feeling of it around my wrist. Like handcuffs. I think Mina and Courtney still have theirs; I don’t know what happened to mine.

“Ah Poh was tiny, like five feet tall at most, and every year she got a little shorter. She wore these quilted floral vests, and she had that hunch old Chinese ladies get—you’ve seen them, if you’ve ever set foot in Chinatown. Quasimodo, my sisters and I used to call her, until Mom heard us one day and smacked the shit out of us. It’s osteoporosis, that’s what I learned later, due to childhood lack of calcium. Tiny fractures in the spine that break and reheal over and over, like a cup that’s been mended with too much glue. At least, that’s what they told us in premed.

“But don’t get me wrong—Ah Poh looked like a sweet little old lady, but she was fierce. One time on Grant, this guy tried to grab her bag. She wouldn’t let go. She yanked it back so hard he lost his balance. Then she gave him a royal cussing-out so loud he just lay there, like he’d been fire-hosed.When she finished, all the shopkeepers were frozen in their doorways, spectating, and the guy scrambled up and took off. I remember I was just standing there, holding the pink plastic bag with the fish and the bunch of bok choy we’d bought for dinner, and Ah Poh turned to me and said,‘Okay, come on, neui neui, let’s go home.’ Like nothing had even happened.

“Well, after my sisters and I went off to college, we were grown up, we were busy, we were dating and working, and we didn’t call home as often. Ah Poh started doing the typical grandmother thing: nagging at us about being single, how we’d better hurry up and find somebody. ‘Aren’t you lonely,’ she’d say over the phone, ‘without a family, how do you have a purpose in life.’ I suggested this was projection on her part—with all of us gone, she had a lot of time on her hands.

“‘Nuh-uh,’ she said, ‘don’t you try that psycho-ology on me, neui neui.That doesn’t apply to Chinese people.That’s only for gweilo.’

“I had switched from premed to psychology by then, and she was the only one who wasn’t giving me a hard time about it. My parents, of course, didn’t consider psychology medicine—they wanted me to be a real MD doctor. In fact, I think they’re still holding out hope. It’s a stereotype, but it exists for a reason, you know? What it is, is that they went through so much to get here.They think about Ah Poh growing up in the middle of that rice field, and all those years of scrimping to pay tuition, and we’re just going to throw all that away and follow our dreams and become poets or postmodern interpretive dancers or whatever? We’re their investment on their down payment of suffering, and they are for damn sure going to get their returns.

“Anyway—Ah Poh kept giving me a hard time about not having anyone.

“‘What happened to that Alex?’ she said. ‘I thought that was going so well.’

“Alex had recently left me for my friend—now my ex-friend— and on top of that he still owed me nine hundred dollars that I’d lent him, which I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to get back. When I told Ah Poh that, she made a clicking noise with her teeth.

“‘Okay,’ she said, ‘I tell you what, neui neui. I’m going to curse him.’

“Ah Poh had plenty of superstitions, we’re a superstitious people— though maybe everyone is. Don’t turn the fish over on the platter or your boat will overturn. Don’t put your purse on the ground or you’ll become poor. Don’t give scissors and knives as presents or you’ll cut the friendship in two. Don’t say the number four. As kids, we couldn’t turn around without stubbing our toes on another thing that would bring us bad luck. But cursing is not any ancient Chinese practice I’d ever heard of.

“‘What do you mean, curse,’ I said.

“Apparently, she’d learned it from her friend Marcie, who she met playing bingo at the neighborhood church on Tuesday mornings.

“‘I thought you thought bingo was boring,’ I said.

“‘I do,’ she said, ‘but it turns out, so does Marcie. So I taught her mah-jongg, and now we play that every week instead. And we go to the casino on Thursdays. Senior discount day.’

“‘Wait, what do you play at the casino?’ I asked.

“‘Slots,’ she said—a little surprised, like it was so obvious. ‘Sometimes some blackjack, too.’

“Marcie had a ritual: whenever someone wronged her, she’d write their full names on a slip of paper, roll it up, and freeze it into an ice cube. And then leave it there in the freezer. Forever.

“‘It works,’ my poh poh insisted. ‘This contractor overcharged Marcie for repairing the roof, so she wrote his name and froze it.Two weeks later, he got sued by the city for letting his license lapse.You tell me that Alex’s full name. I’ve got a piece of paper right here.’

“I didn’t feel I had anything to lose, and anyway arguing with Ah Poh was usually a losing battle, so I recited Alex’s full name—first middle last, right down to the III—and she wrote it on a piece of paper and told me she’d pop it into the ice cube tray as soon as we hung up. “And wouldn’t you know it, a month later I heard through the grapevine that my ex-friend cheated on Alex with his sister—and now they were a serious thing, and a week or so after that I saw pictures of her three-carat engagement ring on Facebook.

“After that, my sisters and I started calling Ah Poh whenever we had grievances we couldn’t right through regular, non-curse means. When Mina got understudy in her show, Ah Poh froze the actress who got the lead, and just a few days later she broke her foot and Mina stepped in. When Courtney’s boss at the firm made a pass at her, Ah Poh wrote down his name, and later that year he got caught falsifying evidence and was disbarred. And when the neighbor across the street from my parents hung up his ‘Trump’ sign, with ‘Send Them Back’ hand-scrawled across the top, she wrote his name down, too. My mom said last she heard, he got shingles and had to stay inside for months. We’d call Ah Poh with an update each time we heard another justified misfortune. ‘Guess what,’ we’d say, and inject the next little hit of schadenfreude.

“She took it seriously. She kept those ice-cube curses in there, in a gallon Ziploc bag at the back of the freezer behind the ice cream and turkey leftovers. One time, when I was still living in the Bay Area, she called me.

“‘Power’s out,’ she said.

“‘Ah Poh, are you okay?’ I asked.‘You need help?’

“She made that clucking noise again. ‘I’m fine,’ she said, ‘I’m not afraid of the dark. But listen, neui neui, your mom’s not home, and I need you to do something.’

“What she wanted was for me to come by with a cooler full of ice. “‘Ah Poh, I just got home,’ I said. I was living in Oakland then, and

I didn’t want to cross the bridge for the third, and then fourth, time that day.

“‘Aiyah,’ she said. ‘All these things I do for you all these years, and you won’t do this one little thing for me?’

“When I arrived forty-five minutes later, lugging the big red-and-white Coleman cooler I used on camping trips, she met me on the steps with the bag full of curses in hand.

“‘Good girl,’ she said. She swiveled the cooler open and nestled the bag down into the ice and shut it again, her jade bracelet clink-clinking against the lid.‘There,’ she said.‘That should hold it until the power comes back on.’

“It did, and in the morning, when I called to check on her, the first thing she told me was that the cubes were back in the freezer. Not a single one had melted.

“She died last fall, at the ripe old age of ninety-six, shorter and fiercer than ever, still going to the casino with Marcie in her big old visor hat right up to the end. I’m glad, in a lot of ways, that she went before all this started. Believe me, she’d have a lot to say about Covid and all of it. Pity the poor soul who might have said any of that ‘China virus’ bullshit in her hearing.

“Anyway. I went home in February, right before everything shut down, to help my mom sort through Ah Poh’s things. The last night I was there, when everyone was asleep, I went to the freezer.The curses were all still in there, little frosty cubes with the slips of paper cloudy white inside. I wanted to know the full scope of our anger. To see them all laid out in front of me, all the people who’d done us wrong over the years. Who had my poh poh written down for herself? Who were the ones who’d done her wrong?

“I spread the ice cubes out on the table and watched them melt, slowly.The kitchen was cold, and it took a long time. But finally, there they were: little rolls of paper, finally freed, soggy in the growing puddle. I started to unwrap them.

“And would you believe it? They were blank. Every one of them. Just blank slips of paper rolled up and frozen in ice. I still don’t know what to make of it.‘Psycho-ology,’ Ah Poh would have said.”

__________________________________

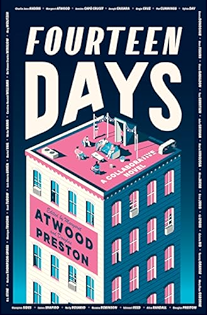

From the book FOURTEEN DAYS: A Collaborative Novel edited by Margaret Atwood and Douglas Preston. Copyright © 2024 by The Authors Guild Foundation. Published on February 6, 2024 by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpted by permission.