Forbidden Cities: How Palestinians Manage To Cross Occupation Lines

Ahed Tamimi and Dena Takruri on Visiting a Fractured Homeland

One of the most memorable days of my childhood was when my family took a trip to Akka (also known as Acre), a picturesque coastal Palestinian city that was taken by Israel in 1948. It was my first and only time seeing Akka, but I was so enamored of what I saw that the details are forever etched in my memory.

It was the holy month of Ramadan, which meant that on Fridays, Israeli authorities granted some Palestinians from the West Bank rare permits to go to Jerusalem and pray at Al-Aqsa. Only women and girls, boys under seventeen, and men over forty were eligible. Luckily for my family, we all met the age qualifications. On this particular Friday, though, my parents decided to take advantage of the access to the 1948 lands that we’re normally forbidden to visit and venture out to Akka. And this meant that for the first time in my life, I’d get to see the Mediterranean Sea up close.

When speaking of the villages and cities stolen from us in 1948, most Palestinians will hardly ever refer to them as “Israel.” Instead they use ad-daakhil, which means “inside”; “the 1948 lands”; or, more simply, “1948” or just “’48.” It’s an affirmation of our continued claim to the land and a constant reminder of the tremendous losses we suffered just decades ago—a still-fresh wound.

I grew up hearing romanticized depictions of the cities and villages of 1948 and imagined them as forbidden lands, fabled places of beauty and splendor.

One of the greatest pains to our existence as Palestinians is that despite living in such a geographically small area—historic Palestine is roughly the size of New Jersey—we’re cut off and isolated from one another. Palestinians from the West Bank, like my family, must remain only in the West Bank. The 2.2 million Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, a tiny enclave that Israel has blockaded by air, land, and sea since 2007, are literally trapped there, in what’s called the world’s largest open-air prison.

Those of us in the West Bank and Gaza are disconnected from one another and from our Palestinian brethren who live in occupied East Jerusalem and in the cities within ’48. The Palestinians of ’48, the ones who managed to stay in their villages despite the Nakba, now make up 20 percent of Israel’s population. But, thanks to Israel’s systemic discrimination and the institutionalized racism that defines Palestinians’ existence there, they live as second-class citizens. Most of us in these disparate territories cannot visit one another. This form of divide and conquer is imposed by Israel as yet another method to control us. As a result, we’re fragmented as a Palestinian nation and lack the social cohesion and unity needed to achieve self-determination and, ultimately, liberation.

I grew up hearing romanticized depictions of the cities and villages of 1948 and imagined them as forbidden lands, fabled places of beauty and splendor. “The Israelis took our most beautiful cities” is a common refrain I’ve heard since childhood.

From the hilltop near our home in Nabi Saleh, I could stare out at Tel Aviv and catch glimpses of the distant sea. I fantasized about how life there used to be and what it might be like currently. Tel Aviv should only be a forty-five-minute drive from Nabi Saleh, but given the checkpoints we’d have to cross and the nearly impossible permit we’d have to get from Israel, it might as well be in another country.

Imagine having parts of your ancestral homeland totally off-limits to you. They’re within sight, but completely out of reach. Such deprivation tears at your soul. It gnaws away at you. At times, you want to break down and cry. Other times, you want to destroy the apartheid wall and dismantle the checkpoints with your bare hands.

Even more infuriating is knowing that practically any Jewish person in the world can immigrate to Israel and get citizenship, even if they had never previously stepped foot in the country. And that so many tourists from around the world can easily see more of your country than you’ll ever be able to, despite the fact that you’re indigenous to it. While they can breeze right through Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv, you need permission from the state that stole your land. And you’re very lucky if you get it.

This is why our day trip to Akka was monumental.

On the drive there, my brothers and I could hardly contain our excitement. Abu Yazan had his nose pressed to the window practically the entire time, eager to be the first one to spot the sea. As soon as we arrived in Akka’s Old City, we bolted out of the car and began exploring our surroundings. My jaw dropped in awe as I took in the scene of the historic port city around me. Akka was more magnificent than I could’ve imagined.

It contained hundreds of years of history, including relics of the Crusaders. The ancient, well-preserved walls that surrounded the Old City teleported us back centuries to when the Ottoman Empire ruled our land. My father explained how those walls helped determine Napoléon’s defeat in Akka, which ultimately crushed the world-renowned conqueror’s dreams of carving out an empire in the East. It made me love the city even more.

Unlike many other cities within ’48, Akka still has a significant Palestinian population. I heard Arabic spoken everywhere we went and instantly felt right at home. I loved walking down the bustling old harbor with its fishermen, vendors, and children running around playing. With each inhalation of the salty, fishy scent filling the air, I felt more alive.

My brothers and I raced over to the ancient seawall encircling the Old City and watched in amazement as local boys jumped off it and plunged right into the blue Mediterranean Sea. It didn’t matter that I couldn’t swim well. I was inspired to dive right in after them, but just as I tried to hoist my body over the wall, my dad grabbed the back of my shirt. My brothers’ attempts to imitate the boys’ jumps were similarly intercepted. Still, that seawall stood out as my favorite part of the city.

Such deprivation tears at your soul. It gnaws away at you. At times, you want to break down and cry.

There, in Akka’s Old City, I felt transported to the past, but also to an alternative present, a realm of what was and what could have been had Israel not conquered our land and exiled us from it. I also caught a glimpse of a possible future when we could return to this land. I felt a sense of nostalgia, loss, and hope all at once.

So this is what I’ve been missing out on, I thought.

A charming old Palestinian house built of stone that sat by the water captured my imagination. To enter it, you had to walk through a tiny turquoise door that was rounded at the top. I wondered who the inhabitants of this enchanting little dwelling were and if they knew that they were the luckiest people in the world.

“I wish it were mine!” I told my family longingly. In that moment, a new dream took root inside me: to move to Akka one day and live right by the shining sea.

My parents honored their promise to us and saved the best for last, letting us end the day at the beach. I ran into the water and stayed there for hours. My brothers and I excitedly splashed around and squealed with joy—thrilled to finally experience the privilege of swimming in the sea, which we had long imagined and fantasized about. Something in its vastness, and in the fact that there was only water as far as your vision could stretch, made me feel free for the first time in my life. No settlements, no wall, and no checkpoints to mar the landscape. Just sea. It was the most beautiful feeling of my life, a literal dream come true, and I never wanted it to end.

We swam until the sun set and a chorus of adhan, signaling the hour for the Maghrib prayer and the end of the day’s fast, rang out from the colorful minarets of the old mosques around us. That’s when our parents called for us to get out of the water and begin drying off so we could begin the two-hour journey back home.

But I wasn’t ready to leave.

I remained in the water, trying to soak up as much as I could, not knowing if I’d ever be able to come back. Baba eventually had to wade in and drag me out, scolding me while doing so. I threw a small tantrum and tearfully insisted to my parents that I wanted to stay. I wasn’t done smelling the soil of Palestine there. I hadn’t yet had my fill.

On the car ride home to Nabi Saleh, I felt increasingly suffocated with each checkpoint we crossed. The world was closing in on me once again, and I’d soon be returning to my life of constant army raids and arrests, clashes, and closed military zones—a life of endless limitations and dreams denied. I love my village with all my soul, but I felt a strong sense of belonging in Akka. And I left a part of myself there. Akka was a part of my homeland that was foreign to me, and I deserved to get to know it. I now understood with every fiber of my being that it was the birthright of every Palestinian to do so.

My Affection for Akka is rivaled only by my deep love for Jerusalem, our cherished holy city of Al-Quds, which is unlike any other place in the world. Walking through the Old City of Jerusalem is best described as an exhilarating assault on the senses. The air is thick with the aromas of freshly baked ka’ak bread, spices, incense, Arabic coffee, and falafel all blended together. If Palestine could be bottled as a scent, it would smell like this. A maze of narrow alleys with cobbled streets ensures you can walk around for hours and never walk down the same alley twice. Along the way, you pass countless shops with their colorful displays of Holy Land souvenirs, spices, candy, fresh juice, jewelry, clothes, and shoes.

Jerusalem teems with religious, historic, and political significance and is as coveted as it is contested. Sadly, I’ve been there only a little more than a handful of times, but each trip further deepened my attachment to the city. In the Old City of Jerusalem, the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish quarters are home to some of the holiest sites of the three major Abrahami faiths.

There’s the Western Wall, sacred to the Jewish people; the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which Christians believe to be the site of the crucifixion and burial of Jesus; and the sacred Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, where the Prophet Muhammad prayed with the souls of all the other prophets and ascended to heaven. Jerusalem is the third-holiest city in Islam and preceded Mecca as the first qibla, the direction toward which the Prophet Muhammad and the early Muslim community faced to pray. Beyond that, the city is central to the Palestinian struggle and integral to the soul of every Palestinian, Muslim and Christian alike. It’s our eternal capital.

[Jerusalem] is central to the Palestinian struggle and integral to the soul of every Palestinian, Muslim and Christian alike. It’s our eternal capital.

I sneaked into the city for the majority of my visits, and I chose to do so out of principle. I refused to seek the permission of my oppressors to visit a city they’re illegally occupying. Instead, I rode with family friends whose car bore a yellow license plate, hoping not to get stopped and searched at any checkpoints, banking on my ability to pass as a foreigner with my blond hair and blue eyes, to quell any suspicion the soldiers might have. The privilege of being unrecognizable is one that I continue to mourn intensely now that I’m well-known in Israel and easily identifiable.

Each time I arrived in the Old City and began to walk down the old steps at the Damascus Gate, I felt the same magnetic pull. There was always the same special energy buzzing in the air, energy that drew me in and made me feel as though I were traveling back in time through the various eras in which the city was conquered, destroyed, and rebuilt time and again. Standing there within the ancient walls that had hosted so many civilizations, religions, and empires made me proud to be a daughter of that land.

Each time I approached the Damascus Gate, I was captivated by the sight of the hajjehs, the elderly Palestinian women, sitting on the ground with okra, mint, grape leaves, or whatever other produce they selling splayed out on newspapers in front of them. The hajjehs managed to command my respect and adoration at the same time. I’ve always fantasized about spending days on end with them, sitting right beside them on the ground and getting to know each of them one by one. I see them as living, breathing Palestinian history books and priceless national treasures. I imagine asking them all the burning questions that float in my mind:

Were you around in 1948, during the Nakba?

What was your experience like?

What was life like when you were my age?

Are there any martyrs or prisoners in your family?

What did you do during the First Intifada?

How did you confront the occupation?

From the moment I first saw those hajjehs, they’ve never left my mind. To this day, I still dream of hanging out with them.

It’s the small details that define Jerusalem and make me love it: the vendors pushing their carts stacked with goods as they try to squeeze their way through the crowded alleys; the resonant sound of the church bells ringing; the shimmering golden glow of the majestic Dome of the Rock, which never fails to take my breath away; the beauty of the ancient stones in the walls; the various worshippers embarking on their unique spiritual journeys; the rich diversity found in the historic quarters inhabited by Palestinians of African, Moroccan, and Armenian descent, a reminder of how many people traveled from afar to make the magnificent capital their home. These are just some of the tangible things that tie the Palestinian people so intimately to Jerusalem.

There are also the intangible.

Even more than Akka, Jerusalem’s Old City feels like a portal to the past and, at the same time, an elusive glimpse at a possible future. It’s one in which Palestinian Muslims and Christians can once again peacefully coexist with our Jewish brothers and sisters in a single state. But through its calculated efforts to erase the Palestinian presence in the city, Israel has crushed all hope of that vision being realized anytime soon.

If we give [Jerusalem] up, it means giving up the Palestinian cause. And that’s something we’ll never do.

In my romanticized memories of Jerusalem, I didn’t always account for the ugliness that also defines the city—to which it’s impossible to turn a blind eye. You see it in the armed Israeli soldiers patrolling the Old City, bumping into you with assault rifles flung across their chests. You see it in the young Palestinian men who are routinely stopped by soldiers and forced to endure humiliating body searches simply because they’re Palestinian. You see it in the giant Israeli flags that hang from the balconies of homes that once belonged to Palestinians.

As part of the Zionist state’s long-standing plan to claim the whole city as its undivided capital, Israel is undertaking a steady ethnic cleansing of Jerusalem’s Palestinians. This systematic attempt to demographically alter the makeup of Jerusalem by increasing its Jewish population plays out through the impossible set of conditions it imposes on Palestinians, which force many to leave or punish them if they stay. This includes revoking Palestinians’ residency permits, forcibly displacing them, banning the construction and expansion of homes to accommodate growing families, and demolishing homes to clear the way to build more illegal Jewish settlements.

Israeli courts have even recently ruled that Jewish settlers can move into Palestinian homes in the East Jerusalem neighborhoods of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan and forcibly expel the Palestinian families that have been residing in them for generations. There’s even a campaign being carried out by right-wing Israeli activists to cover or scratch off Arabic names from street signs around the city, leaving only the Hebrew and English names displayed.

But under international law—and like the West Bank—East Jerusalem, which includes the Old City, is considered occupied Palestinian territory. It has been so ever since it fell under Israeli military rule in 1967. Additionally, since 1948, the United Nations and most of the international community have refused to recognize any country’s sovereignty over any part of the city until a permanent peace agreement is reached.

This was also the United States’ position until 2017, when the Trump administration recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, an inflammatory move that had far-reaching Repercussions for the Palestinian people, the region, and for me personally. For it was during the aftermath of this announcement amid heightened tensions that I was arrested.

Jerusalem is and always will be the most important city for the Palestinian people. If we give it up, it means giving up the Palestinian cause. And that’s something we’ll never do.

_____________________________________

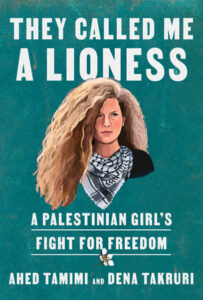

Excerpted from They Called Me a Lioness: A Palestinian Girl’s Fight for Freedom by Ahed Tamimi and Dena Takruri. Copyright © 2022. Available from One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Ahed Tamimi and Dena Takruri

Ahed Tamimi is a Palestinian activist from the village of Nabi Salih in the occupied West Bank in Palestine.

Dena Takruri is a presenter and producer for AJ+, a digital media venture by the Al Jazeera Media Network.