5 Great Books You May Have Missed in September

Including Megan Gail Coles, Anja Kampmann, and More

Each month I have to make hard choices for this column. I comb through hundreds of titles and usually wind up with 40 to 50 worthy contenders, which I then have to whittle down to just five books to read and champion.

I may have mentioned all of that before, but I mention it again this month because, by the time I’ve done this again, we’ll have been through a presidential election—and the choice there is not hard. We all know what to do. Please get out and vote so that we can continue to live in a society where as many books are published as possible. Even if I’m preaching to the choir, I hope my plea makes what we sing together strong, stronger, strongest. See you on the other side.

*

Megan Gail Coles, Small Game Hunting at the Local Coward Gun Club

(House of Anansi Press)

Given these times, seems like as good a title as any to start: Small Game Hunting at the Local Coward Gun Club has won awards and accolades in Canada, and many more US readers deserve to know about this new novel from Newfoundland (slogan: “Not just The Shipping News any more!”). It’s the dead of winter in downtown St. John’s, and inside The Hazel restaurant the season affects everyone whether they have a disorder, or not. Outside, on the very cold street, a woman named Olive watches the staff and locals. “Mondays are for quitting everything. Again. Except when it storms on Monday. Then quitting everything is pushed to Tuesday.” The author, an established playwright, uses her knowledge of drama to great effect in her first novel, pushing and prodding the characters on their small stage inside themselves, between each other, and into the larger world, until Olive and one of the other women come to a place where neither can lie anymore. The author, whose ancestry is “English, Irish, and M’ikmaq,” provides a story so direct and painful that her dedication reading “This might hurt a little. Be brave.” should be heeded.

Linda Kass, A Ritchie Boy

(She Writes Press)

Linda Kass’s A Ritchie Boy is one of the rare World War II novels that actually illuminates an aspect of that war most people haven’t already heard about. The Ritchie Boys were a troop of young men recruited by the US military to work as interrogators of German prisoners and counterintelligence operatives—and about 14 percent of them, because of their language ability, were Jews of German origin or ancestry. The “Ritchie Boys” were named after Camp Ritchie, Maryland, where they were trained. One of them was J.D. Salinger. Kass, whose father Ernest Stern was a Ritchie Boy, uses interconnected stories from different perspectives to follow her character Eli Stoff as he emigrates with his parents from 1938 Austria, to his enlistment five years later in the US military, on to his work in Europe, then in peacetime. The novel’s structure offers a portrait of a time as well as of a man caught up in its turmoil.

Anja Kampmann (trans. by Anne Posten), High as the Waters Rise

(Catapult)

High as the Waters Rise by Anja Kampmann (trans. by Anne Posten) won the Mara Cassens Prize for best debut in Kampmann’s home country of Germany, along with several other awards and nominations, a first novel from a poet whose dissertation was on silence and musicality in the works of Samuel Beckett, so it’s wonderful to see her words translated by Posten, who works in poetry and drama as well as prose. The story is tragic: Waclaw and Mátyás work and bunk together on a North Atlantic oil rig. One night, Mátyás disappears, fallen into the sea. In his grief, Waclaw travels, searching for the reasons and meaning behind his friend’s death. He can’t go home: “. . .the address he had listed as his emergency contact no longer existed.” His travels, which start in Morocco, are both a journey for Mátyás and their friendship, and a series of encounters with other people on the socioeconomic margins. It’s a novel that manages to be beautiful and affecting without the slightest lapse into sentimentality or heaviness.

Fabienne Kanor (trans. by Lynn E. Palermo), Humus

(CARAF Books/University of Virginia Press)

In Kampmann’s novel men cling to a steel platform to survive the ocean. In Humus by Fabienne Kanor, trans. by Lynn E. Palermo, an older and even more tragic tale comes to light. Published in France in 2006, this important book is now released in English by the Caribbean and African Literature Translated from French (CARAF) Books arm of the University of Virginia Press. Author Fabienne Kanor, born in France to parents from Martinique, found a report in a library in Nantes about a slave ship called Le Soleil. Its captain, Louis Mosnier, recorded a loss of valuable “cargo.” That “cargo” was human beings, 14 African women who escaped from their imprisonment in the ship’s hold and chose to leap overboard rather than face enslavement. Half of them were drowned or eaten by sharks. One died after being hauled back on board. Kanor writes, “Like these shadowy figures put in chains long ago, the reader is condemned not to move from this moment on. Just listen with no other distraction to this chorus of women. At the risk of losing your bearings, hear once more these hearts beating.”

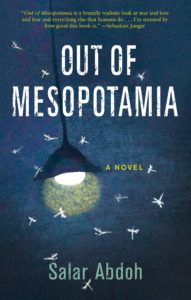

Salar Abdoh, Out of Mesopotamia

(Akashic Books)

Salar Abdoh’s Out of Mesopotamia should remind any reader that, depending on what side we’re on in war, we quickly forget the other side’s humanity—and that the other side is reacting and responding to what’s happening, too, especially when the violence and brutality is taking place on their soil. The protagonist of Abdoh’s new novel is Saleh, an Iranian journalist who can’t resist reporting from the front lines in Iraq and Syria. When he returns to Tehran, he can’t reconcile his adrenaline-driven self with civilian life—even though he knows what he witnesses is often savagery. This book was reviewed in The New York Times by acclaimed US novelist Elliot Ackerman—certainly not overlooked. However, it deserves a much wider readership than those who might usually be interested in what are too easily labeled “war novels.” Abdoh wants to write about what happens to a person who goes back and forth between war and peace, what happens to art in a society engaged in a “forever war,” and what it means for our souls that humans cannot live without conflict.

Bethanne Patrick

Bethanne Patrick is a literary journalist and Literary Hub contributing editor.