Five Books Making News This Week: War, Cults, and Poets

Alan Furst, Mary Roach, Emma Cline, and More

In response to violence, poetry. On June 3, Juan Felipe Herrera, who has just begun his second term as U.S. Poet Laureate, offers up a poem entitled “Where We Find Ourselves.” Its dedication: “In memory of professor William Klug and the students of UCLA, 6-1-16.” What better way to show us what a nation’s bard can offer. A Dylan Thomas award-winning novel about grief impresses U.S. critics, Craig Morgan Teicher’s Delmore Schwartz collection may revive a literary career, Mary Roach takes on humans at war, Allan Furst delivers a “lyrical” thriller set in Occupied France, and a first novel by Emma Cline brings back the Manson clan, with a difference.

Max Porter, Grief is the Thing with Feathers

Porter’s novel won this year’s Dylan Thomas award. Swansea University professor Dai Smith, the head judge, says Porter’s book “did something unique, something none of us had ever read before … It fits in so much with the echo of Dylan Thomas, who moved so effortlessly between prose, poetry, gothic surrealism and black comedy. And there it was, bounding out of this little volume. I picked it up without great expectations – what is it? a prose poem? a novella? But it’s a hybrid, as Max himself has said, and that means it is like nothing else.” Grief also was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award and the Goldsmiths Prize before reaching the U.S., where critics are ecstatic.

“The Emily Dickinson–derived title and featherweight of this remarkable volume should alert you that it is more prose poem than novel, but no less capacious for that,” notes Ann Hulbert (The Atlantic). “Grief,’ the bird says and Porter brilliantly shows, is the fabric of selfhood, and beautifully chaotic.”

“As resonant, elliptical and distilled as a poem, Grief Is the Thing With Feathers is one of the most moving, wildly inventive first novels you’re likely to encounter this year,” writes Heller McAlpin (NPR). “It’s funny — in a jet-black way — yet also fiercely emotional, capturing the painful sucker-punch of loss with a fresh immediacy that rivals Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. But the mournful magical thinking of Porter’s widower stretches over years. ‘Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project,’ he writes. Grief, he adds, is ‘the fabric of selfhood, and beautifully chaotic.’”

A.N. Devers (Los Angeles Times) raves: “Grief Is the Thing with Feathers argues that books, literature and poetry can help save us. This book is a sublime and painful conjuring of a family’s grief and the misfit creature with the power to both haunt and help them. It is a complex story, not simply-told or sparse: Nothing is missing. Let it be a call for more great books of this length to be recognized for what they are — whole. Extraordinary is a book with feathers.”

Craig Morgan Teicher, Once and for All: The Best of Delmore Schwartz

Jonathan Galassi (New York Review of Books) reminds us that Delmore Schwartz called his group of East Coast writers “the class of 1930,” and “besides him they included his younger compeers John Berryman, Randall Jarrell, and Robert Lowell. (Their female counterparts Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, and others lived their own various versions of the myth.) All would have troubled lives and die early or unnatural deaths.” “There’s a lot for us now in his work,” Teicher, the editor of this gathering of Schwartz’s poetry, fiction, drama, criticism, and letters,” writes on Facebook. “He was an over-sharer more than half a century before Facebook, and a writer who didn’t confine himself to one genre. I hope Once and For All makes him some new friends.”

Adam Kirsch (Tablet) calls Once and for All “an ideal introduction for the curious reader. It includes enough of Schwartz’s early work—including selections from ‘Genesis’—to show why he became a legend, and enough of the later work to show how the legend faded. And since it includes a handful of letters, it allows the reader to trace Schwartz’s evolution and decline.”

“Ashbery, at the end of his introduction, points out that ‘the critics were premature in condemning the late work of Picasso and Stravinsky,’” points out Jonathon Sturgeon (Flavorwire). “Perhaps, he wonders, ‘Delmore will one day get a similar reprieve.’ Maddeningly, he then claims that he will ‘leave it to you to decide’ before confessing that ‘Summer Knowledge,’ a late poem written while Schwartz was arguably on the decline, achieves ‘a new kind of telling… with an urgent bluntness of his own.’ If John Ashbery thinks a book contains an overlooked mutation in American poetry, you’d better check it out.”

“This new collection of Delmore Schwartz’s work reads like a literary ‘CV of Failures,’ a powerful testament to a life shaken by the Great Depression,” writes Jason Boog (Los Angeles Review of Books). “As we navigate the long road to national recovery, we can use his writing both as a mirror and as a compass.”

Mary Roach, Grunt

Roach has made an art of popularizing science in witty terms, writing about written about digestion (Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal), cadavers (Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers), and space (Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void). This time around she’s focused on “the curious science of humans at war.” She spoke with NPR’s Terry Gross about maggots and the runs, and acknowledged, “I’m kind of the bottom-feeder of science writing. I’m just someone who is OK with being very out there with my curiosity.”

“Roach’s books are models of good popular science writing,” writes Adam Woog (Seattle Times). “One way or another, each stands at the intersection of science and the human body.”

Caitlin Flanagan (Washington Post) notes that Roach’s new book “brings the breezy, jokey, boosterish approach that fans have come to expect of her work to a dark new subject: how military scientists try to anticipate, prevent or mitigate the ravages of war — from debilitating injuries to violent death — on its combatants.

The tone is jarring, but the reporting is sound.”

Alan Furst, A Hero of France

In the 15th of Furst’s series of novels set in Europe during the interwar period, Furst follows one Resistance cell through five months in March 1941, nine months into the German occupation. The novel’s hero, Mathieu, is charged with taking a downed R.A.F. airman safely from the countryside to Paris, so he can be transported back home to England. Kirkus Reviews calls it “lyrical” and concludes, “This daydream of life under the Occupation is something rare: a suspense novel that offers the pleasures of relaxation.”

“Furst, who is known for his detailed research into both cat-and-mouse sides of occupied Europe, shows not just Mathieu and his comrades but also all kinds of Germans, including the police and the Gestapo,” writes Sara Paretsky (New York Times Book Review). “And he shows us the French punks who are ready recruits for the occupiers, not out of any particular ideology but because of the restless savagery young men on the margins often exhibit.” Paretsky speculates about the popularity of Furst’s novels: despite their European setting, she writes, “they can be read in the tradition of the American western. Like Shane, Furst’s heroes tend to be loners — Marlboro men, we used to call them in the days of cigarette ads. They take on the burden of an entire city or country. And while they may work with a group, as Mathieu does, they carry the responsibility of that group on their own shoulders….We all hope in our secret selves that we would be risk-takers like Mathieu, that we would stand with truth and justice in dire times, that we wouldn’t keep our heads down, looking the other way when the police wagons passed by.”

Richard Lipez (Washington Post) concludes, “Furst rolls all of this out with his usual steady-as-she-goes pacing and a prose style that nicely mixes the elegant and the matter-of-fact. And it’s not giving anything away to say that in the end, many readers will want to stand up and sing ‘La Marseillaise’ through their tears.”

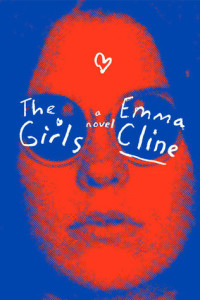

Emma Cline, The Girls

A first novel that is part of a $2 million three-book deal draws scrutiny, and measures up, ending up on lots of summer “to read” lists and keeping reviewers turning pages.

Marion Winik (Newsday) was transported. “I missed a meeting at work recently because I was so lost in…The Girls, that I didn’t even look at the clock until it was an hour past time to leave,” she writes. And later, “By using fiction to explore the moral issues raised by a confounding historical event, it takes a shot at greatness.”

Dylan Landis (New York Times Book Review) calls The Girls “a seductive and arresting coming-of-age story hinged on Charles Manson, told in sentences at times so finely wrought they could almost be worn as jewelry. It reimagines the summer leading up to the notorious Tate-LaBianca murders in Los Angeles in August 1969, and it dissects an obsession — but not the one you’d expect.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.