Five Books Making News This Week: Sugar, Satire, and Short Fiction

Gary Taubes, Aravind Adiga, Roxane Gay, and More

What to read in 2017? Check out these lists from the Washington Post, the New York Times Book Review, and Time. (And here’s my take for BBC.com.) Critics find Roxane Gay’s story fiction as powerful as her cultural criticism, a former Beijing correspondent explicates the complexities of U.S.-China relations, an investigative journalist drills down into the health dangers of sugar, a Booker Prize winning novelist follows two soccer prodigies, and The Feud, continued.

Roxane Gay, Difficult Women

Essayist, novelist, and cultural critic Roxane Gay’s first short story collection collects 21 stories with truth and bite. A book to read slowly, and save.

Renee Graham (Boston Globe) writes, “The great James Baldwin once said, ‘You want to write a sentence as clean as a bone. That is the goal.’ In Difficult Women, Gay achieves that goal. Her writing is unfussy, well matched to the women and men she’s created, and she finds a distinct rhythm both elegant and plainspoken.”

“Fans of writer Roxane Gay won’t be surprised to hear that her new short story collection . . . deals with such subjects as sexual relationships, motherhood and body image, or that the stories’ tones range from comic to harrowing, sometimes in a paragraph or two,” notes Colette Bancroft (Tampa Bay Times). “But they might be surprised that, though many of the stories are realistic, quite a few venture into the territory of magical realism. In one, a small town copes with life after the sun vanishes; in another, a man marries a woman made of glass, her pulsing heart always visible.”

“Gay’s women don’t have it easy,” writes Josh Cook (Minneapolis Star-Tribune). “The “difficulty” in the title is their sarcastic comeback to doltish men who don’t understand complexity in general and the complexity of victimhood in particular. The women here are complex, but not in the typical way of fiction. Much like Mireille, the protagonist of Gay’s profound and violent novel, An Untamed State, the women here reveal themselves in how their minds adjust to a world that seems bent on violating their bodies.”

Gary Taubes, The Case Against Sugar

Sugar, writes Taubes in his third book, “triggers the progression to obesity, diabetes and the diseases that associate with them.” His argument is convincing.

Daniel Engber (The Atlantic) writes, “In the past few years, the dangers of dietary fat have begun to look as though they were overstated, and the risks of sugar underplayed. Among the leading advocates for this reappraisal is Gary Taubes, an investigative journalist who has been reporting on nutrition since the late 1990s . . . The Case Against Sugar is a prosecutor’s brief, but fleshed out with four decades’ worth of extra science and a deeper look at both the history of that science and the commercial, economic, and political forces that helped shape it.”

Taubes’ argument is so persuasive, writes Eugenia Bone (Wall Street Journal), that “after reading The Case Against Sugar, this functioning chocoholic cut out the Snacking Bark and stopped eating cakes and white bread. It was easier than I expected: Within a week, I was so sensitive to sugar that I could taste it in the weirdest places; in a restaurant salad, for instance, and in my organic yogurt. When I ate a piece of Thanksgiving squash pie, it made my head buzz.”

Bharti Kirchner (Seattle Times) writes, “In his campaign against this food additive, Taubes sifts through centuries’ worth of data pertinent to the subject. Practically everything one wants to know about sugar—its history, its geography, the addiction it causes—is here.”

John Pomfret, The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom

Pomfret, a former Washington Post Beijing correspondent, explains his title to NPR’s Robert Siegel: “So the Beautiful Country is what the Chinese call the United States—Meiguo. The Middle Kingdom is what the Chinese call themselves—Zhongguo—which is the country in the center of the world.” His book is timely.

“The two and a half centuries of entanglement between American and China are about to reach their denouement,” Simon Winchester (New York Times Book Review) points out. “By 2049, a crucially symbolic date on the Chinese calendar that marks the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic, Beijing intends two things: to have recovered in full all the territory it lost during the long centuries of what it considers insulting foreign interference and to assert itself in and across the Pacific Ocean to the precise degree its duty and destiny now demand. Both aims are well on their way to realization.”

Howard W. French (Wall Street Journal) calls Pomfret’s book “a major new account of the history of U.S.-China relations.” He concludes, “If the new leadership in Washington wishes to get a sense of the broad sweep of American history with China, I can think of few better places to start than this book.”

Aravind Adiga, Selection Day

Adiga won the Booker Prize for The White Tiger. His new novel is a coming-of-age story that follows two brothers from the slums of Mumbai who dream of becoming cricket stars.

Mike Fischer (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel) writes, “The most obnoxious soccer parent is no match for Mohan Kumar, bullying father of two cricket-playing prodigies in Aravind Adiga’s scathingly satiric novel of modern Indian life. Adiga’s title refers to the pivotal day when teens like Mohan’s sons are evaluated and potentially chosen for one of India’s select cricket teams; imagine the NFL’s Scouting Combine and draft, rolled into one.”

“Cricket is, of course, a wonderful way of writing about shattered dreams—both personal and national,” writes Kamila Shamsie (The Guardian). “As such, it isn’t necessary to know the game to appreciate this finely told, often moving and intelligent novel. Cricket here represents what is loved in India, and yet is being corrupted by the changes within the nation.”

“Adiga’s voice is so exuberant, his plotting so jaunty, that the sadness of this story feels as though it is accumulating just outside our peripheral vision,” concludes Ron Charles (Washington Post). “Or maybe we just grow to like this boy too much to acknowledge that’s happening to him. Suspended between ambition and fear, Manju must learn sooner or later that refusing to choose can be just as momentous as any other choice.”

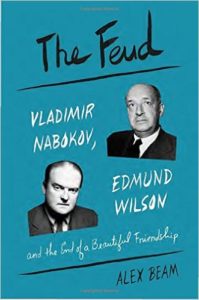

Alex Beam, The Feud

Beam’s brisk and dramatic recap of the Edmund Wilson-Vladimir Nabokov standoff continues to stir critics.

“The Feud shows Nabokov’s mean streak at its most extreme,” writes Jeff Baker (San Francisco Chronicle). “‘He started the quarrel,’ Nabokov told the New York Times about Wilson, another accurate observation, but one that sounds like it was uttered by an intelligent 8-year-old, not the man who thought himself the great writer of the 20th century. Nabokov’s haughty self-regard allowed little room for friendship and left him in self-exile on the upper floor of a Swiss hotel, alone but for the wife who covered for him with pistol and pen.”

“The Nabokov/Wilson contretemps transformed the nature of how authors fight, bringing the literary feud into the modern media landscape,” writes Michael La Pointe (The Walrus). “Indeed, comparing the feuds of Fielding and Richardson’s time to those of the twentieth century is like comparing a fencing match to blitzkrieg . . . ” When did literary feuds become so boring? he asks. “Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson, Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson, Mary McCarthy and Lillian Hellman—these are legendary clashes often mentioned in the annals of literary feuds. But in truth, an authentic literary feud is an extremely rare event. And considering the way we fight now, they’re virtually extinct . . . ”

Laura Miller (Slate) concludes:

Whatever their differences as writers, Nabokov and Wilson were nevertheless writers, and anyone who’s had the opportunity to observe such creatures up close will recognize their propensity toward backbiting, envy, rivalry, shade-throwing, high-horsing, and every other variety of petty competitive behavior. The most sublime and insightful words, more often than not, emerge from decidedly ignoble creatures. You could wring your hands over the misguided senselessness of it all, but it’s saner to follow Beam’s lead and learn to laugh.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.