Five Books Making News This Week: Mornings, Musicians, and Maternity

Janine di Giovanni, Dylan Hicks, Pamela Erens, and More

Ann Patchett’s Commonwealth, Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad, and first novels by Emma Cline (The Girls, about a Manson-style cult) and Nathan Hill (The Nix, set during the 1968 Chicago convention) are among the most grabbed advance galleys at BookExpo America. American Booksellers Association book of the year winners, announced on Thursday, include Lauren Goff’s Fates and Furies (fiction), Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me (nonfiction), and J. Ryan Stradal’s Kitchens of the Great Midwest (adult debut), with Richard Russo as Indie Champion. On Sunday, the pioneering eco-feminist essayist, poet, novelist, playwright Susan Griffin is honored with a Northern California Book Award for lifetime achievement, and a Groundbreaker award goes to William T. Vollmann’s The Dying Grass: A Novel of the Nez Perce War. The NCBA fiction award goes to Joshua Mohr’s novel All This Life. “Sometimes revision feels like being stuck in an M.C. Escher painting,” Mohr told emerging writers on my “demystifying publishing” panel at the Lit Camp on Thursday. Also in the house: Pulitzer awarded authors Paul Harding and Adam Johnson, National Book Critics Circle John Leonard award winner Anthony Marra, Graywolf editorial director Ethan Nosowsky, Buzzfeed’s Isaac Fitzgerald, and Lit Camp founder Janis Cooke Newman.

The Loney, Andrew Michael Murley’s first novel (after two self-published story collections), a British Gothic set in Lancashire, is book of the year in the British Book Industry Awards, besting others on the shortlist of 32, including Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman and Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. Louise Erdrich’s new novel stirs up enthusiasm among critics, Pamela Erens’ third novel takes on the universal and dramatic process of birth, veteran war reporter Jeanine di Giovanni brings back portraits from the war zone in Syria, singer/songwriter Dylan Hicks looks at a group of friends in the post-college years. And Sherman Alexie switches genres, again.

Louise Erdrich, LaRose

Erdrich, who won a National Book Award for The Round House, continues her trilogy of novels circling the concepts of justice with a book in which parents make an “unspeakable gift” in hopes of retribution for the death of a child.

“In the course of 13 novels and numerous short stories, [Erdrich] has laid out one of the most arresting visions of America in one of its most neglected corners, a tableaux on par with Faulkner, a place both perilous and haunted, cursed and blessed,” writes Thomas Curwen (Los Angeles Times). “LaRose is no exception.

Ron Charles (Washington Post) singles out her title character for special praise: “In the vast universe of Erdrich’s characters, this boy may be her most graceful creation. LaRose radiates the faint hues of a mystic, the purest distillation of his foremothers’ healing ability, but he remains very much a child, grounded in the everyday world of toys and school and those who love him.” And, he concludes, “The recurring miracle of Erdrich’s fiction is that nothing feels miraculous in her novels. She gently insists that there are abiding spirits in this land and alternative ways of living and forgiving that have somehow survived the West’s best efforts to snuff them out.”

Michael Magras (Houston Chronicle) writes, “…the beauty of LaRose lies in the unexpected directions in which Erdrich takes her story, set in the years immediately before and after the start of the Iraq War. One of the many themes of this novel is, not surprisingly, the desire for retribution. But Dusty’s death is only the most dramatic event to engender grief and resentment. LaRose is a subtle examination of the sadness that families inflict upon one another and the pull of tradition.”

“For healing, one can only hope there will always be a LaRose,” writes Konnie LeMay (Indian Country Today). “For stories of experiences universal to all and unique to Indian country, one can be satisfied that for this generation, there is a Louise Erdrich.”

Pamela Erens, Eleven Hours

Two women—a laboring mother and her nurse, who is in the early stages of pregnancy herself—are at the center of Erens’ third novel, which takes place in a hospital maternity ward. Erens told NPR’s Melissa Block she chose to restrict the book to 11 hours of labor as a way to give herself parameters. Critics laud her taut and powerful narrative.

“Pamela Erens achieves the extraordinary,” writes Anna Solomon (Boston Globe), “a visceral story about an intensely painful experience that manages to be an intense pleasure to read.”

Lisa Katzenberger (Chicago Review of Books) writes, “After tackling loneliness in her first novel and teenage sexuality in her second, Pamela Erens flawlessly captures the experience of childbirth in Eleven Hours—the fear, the surprise, the other-worldly pain.”

“Thirty pages from the end of Eleven Hours,” writes Jen McDonald (New York Times Book Review), the laboring mother “is thrust into a savage agony, and we find ourselves inside a novel with the adrenaline-rush pacing of an action movie, the gut-turning terror of a horror flick. We are reminded that every birth is an event without script, the ultimate suspense story. Erens registers this without preaching and without judgment, creating one of the most realistic and harrowing portrayals of birth you are likely to encounter in fiction.”

Janine di Giovanni, The Morning They Came for Us

Middle East Editor of Newsweek and contributing editor of Vanity Fair, di Giovanni has reported on nearly every violent conflict since the first Palestinian intifada, with a focus on the human cost of war. Her new book collects her dispatches from Syria, portraits of ordinary people within a jihadist war zone.

Anand Gopal (New York Times Book Review) calls the memoir “a haunting reminder of what the Syrian revolution, ultimately, is about.” He writes:

These days, when politicians bring up the Middle East, they collapse a decade’s worth of occupation, civil war and revolution into a single, ineffable horror: the Islamic State. The idea is that we’ve never seen a group so horrific, so threatening to global stability — which is fueling calls for world powers to ally with, or acquiesce to, Syria’s Bashar al-Assad as a lesser evil in the war against ISIS.

But look beyond this narrow counterterrorism prism and you see the devastating truth: a regime that is willing to rape, torture, starve and gas as many of its citizens as necessary to secure its rule — and in the process, sow such apocalyptic chaos as to help spawn a global refugee crisis and the rise of ISIS. This is the searing lesson of Janine di Giovanni’s heartbreaking [memoir]. Di Giovanni, a veteran foreign correspondent, visited Syria repeatedly in 2012, meeting with civilian activists and doctors, regime soldiers and pro-Assad nuns, and has written a moving portrait of a country divided by and under siege from its own president.

The Morning They Came for Us is a must read filled with bitter realities,” concludes Denise Hassanzade Ajiri (Christian Science Monitor). “It is a call to the outside world not to forget what is happening in Syria.”

Dylan Hicks, Amateurs

A second novel from Minneapolis singer-songwriter Hicks follows a group of friends over several years, emphasizing literary envy and coming of age in the post-college years. Hicks’s playlist for Large-Hearted Boy leads off with the Incredible String Band’s “The First Girl I Loved.” “Their music has a sort of sylvan (or gnomeish) mystery about it, and is one of hippie eccentricity’s purest expressions,” writes Hicks, establishing the tone for Amateurs.

There’s plenty of “dark, knowing humor” in Amateurs, writes Michael Schaub (Los Angeles Times). “It’s a bright, perceptive story about friends trying with mixed results to wrestle with the pressures of adulthood, from the end of college in 2004 through the 2008 recession to a 2011 wedding.” The novel’s themes of friendship, love, envy, he adds, “could potentially make for a maudlin novel. But Hicks, while undoubtedly a compassionate author, is never sentimental. He writes with a similar measured earnestness that calls to mind the best of Ann Beattie and Anne Tyler.”

Tobias Carroll (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) focuses on Hicks’ opener, a wedding… “a sprawling, unconventional one, which suits this story of tentative romance and literary jealousy.” This setup, he concludes, “is the stuff of classic comic fiction; the minute details and anxieties that surround its characters, however, are what endures.”

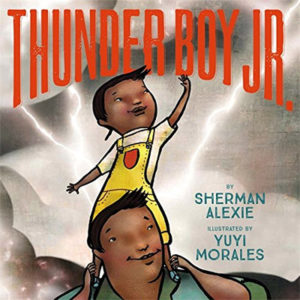

Sherman Alexie, Thunder Boy Jr.

Alexie, who won a National Book Award for his YA novel, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, publishes his first picture book. He goes on the Daily Show, to tell Trevor Noah about his inspiration for Thunder Boy Jr. “I am Sherman Alexie, Jr. The genesis of this book came at my father’s funeral in 2003, where I happened to be standing at the foot of the coffin as they lowered it. They lowered it and there was my name on the tombstone…The existential weight of having my father’s name hit me with such a weight I knew, I have to write about this.”

“The soaring “Thunder Boy Jr.” illustrates the power of words” through an “intentional and personal approach,” writes Minh C. Le (New York Times Book Review). “This first picture book by Sherman Alexie… is illustrated by the much celebrated Yuyi Morales (Viva Frida, Just a Minute). Together they deliver a story that feels both modern and timeless, a joyous portrait of one boy’s struggle to (literally) make a name for himself in the world.”

“Thunder Boy Jr. “is full of spirited fun,” writes Ron Charles (Washington Post), “a delightful story about a Native American boy trying to carve out his own identity….Call it the anxiety of influence for the kindergarten set.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.