Five Books Making News This Week: Apostles and Anthropomorphic Bears

David France, Amos Oz, Yoko Tawada, and More

The shortlist for the Costa Award is dominated by women (14 of the 20 authors in five categories, including Maggie O’Farrell, Sarah Perry, and Rose Tremain in fiction). ‘Tis the season for Best of 2016 lists, leading off with this in the Washington Post, this in the New York Times and this in Newsday. A polar bear in the Berlin zoo inspires a Kafkaesque novel, the protagonist of Amos Oz’s latest looks at Christ’s betrayer, the biography of a Lakota spiritual leader, a history of the AIDs crisis, and more Moonglow.

Yoko Tawada, Memoirs of a Polar Bear (tr. Susan Bernofsky)

Born in Japan, educated in Germany, the multilingual Tawada has won major awards in both countries. During a visit to the Berlin Zoo, she discusses the polar bears that inspired her three-generational story with the New York Times Magazine’s Rivka Galchen.

Clio Chang (The New Republic) notes:

The bears in Tawada’s book all long, in some way or another, for the North Pole, a homeland they have never even seen before—while Knut waits for winter to come in Berlin, he begins to dream of it: “The North Pole had to be as sweet and nourishing as mother’s milk.” In another scene, Knut’s grandmother imagines herself standing on a melting ice floe. “This ice island is still as large as my desk, but eventually it will no longer be there. How much longer do I have?” In these moments, Memoirs seems to ask: What will become of the animals who may soon only live as displaced beings in a world that was once their home?

Tawada “challenges the discreteness of biological species,” writes Steven G. Kellman (Boston Globe). “The novel is a shaggy bear story, one that asks us to accept as perfectly natural the fact that a bear attends conferences and goes to the movies.”

Memoirs of a Polar Bear “hums with beautiful strangeness,” concludes Ramona Ausubel (New York Times Book Review). “Look at the animals we are. Look at us searching for love, for meaning, for our own true forms.”

Amos Oz, Judas (tr. Nicholas de Lange)

The latest from Amos Oz, who described writing a novel to the New York Times’ Roger Cohen as “reconstructing the whole of Paris from Lego bricks,” considers the apostle who betrayed Christ.

“The year is 1959,” writes Nick Romeo (Christian Science Monitor). “The critic of Israeli statehood is a young biblical scholar interested in Jewish views of Jesus; his interlocutor is a retired history teacher who spends his days reading everything from Tolstoy to the Talmud. They rarely agree, and neither is particularly good at listening. Their twisting, searching conversations form the heart of the Israeli novelist Amos Oz’s melancholy new novel Judas.”

Gal Beckerman (New York Times) notes that Judas is “not only titled after the most reviled traitor in history, but also reimagines the story of the Crucifixion, removing the taint from a character who has inspired so much hatred and violence.”

Peter Stanford (The Guardian) calls Judas “many-layered, thought-provoking and—in its love story—delicate as a chrysalis . . . This is an old-fashioned novel of ideas that is strikingly and compellingly modern.”

Joe Jackson, Black Elk

The current standoff on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation adds power to the commentary about Jackson’s biography of Black Elk. Jackson bases the book on historic documents, diaries, records, and on transcripts that led to the Oglala Sioux (Lakota) spiritual leader’s best-seller, Black Elk Speaks, written in 1932 with poet John Neihardt, and revived to great effect in the 1960s.

“Jackson has firmly situated Black Elk in the context of Indian struggles on the plains from 1850 through 1950,” writes David Treuer (Washington Post). “He uses Black Elk to bring home the radical changes that confronted most Indians during this time and, in doing so, creates a deeply felt and personal story of loss and change on the plains.” But Treuer has concerns:

Jackson’s book is replete with troubling language. Throughout, he refers to Indian men as “braves” and Indian women as “squaws,” and often calls young children “papooses.” I am always surprised (but perhaps shouldn’t be) that non-native writers need to be reminded in the 21st century that such terms are offensive and derogatory. These were words that, historically, at least, deprived Indians of their full humanity and are out of place (if not completely inappropriate) in a book that seems to want to do the opposite: restore to individuals their long-denied humanity. As an Indian, I find myself questioning the entire book because of the use of these words. How could this book speak to me, how could it be for me, if my people are described with such disregard?

Ann Neumann (The Baffler) quotes Jackson as she concludes:

“How does one survive in [the modern] world?” Jackson asks. “The Machine is overwhelming and unstoppable, larger than any one woman or man. Black Elk saw it early, though he never used such dystopian terms. Perhaps the only true defense is the most intimate—preservation of one’s soul. Seen like that, his life is more than just another tale of Indian versus white. It becomes instead a parable of modern man.”

That is one way to tell the story of Black Elk: the hopeful way. But there’s another: modernism won, capitalism won; the genocide of American Indians has gone unpunished; and today they live with the highest poverty, unemployment, suicide, and mortality rates in the country. The banner success of Black Elk Speaks and the impassioned testimony of Jackson’s Black Elk can’t change that.

Black Elk’s legacy is a witness—a first-hand account of the horrors that accompanied national expansion and the cruel containment of the native population. It’s also a warning; in celebrating our righteous prophets, we are often too enchanted by their personalities to address the pressing needs of their people.

David France, How to Survive a Plague

France’s AIDS documentary was nominated for an Oscar; his book on the subject is equally gripping.

“All the way through 515 pages of text, I felt I could hear the clock ticking,” writes Cynthia Carr (Bookforum). “It’s both a moving and an enraging read.”

“I doubt any book on this subject will be able to match its access to the men and women who lived and died through the trauma and the personal testimony that, at times, feels so real to someone who witnessed it that I had to put this volume down and catch my breath,” writes Andrew Sullivan (New York Times).

Bert Archer (Toronto Star) writes, “The reporting and research that made this book are exquisite, the scenes and people painted test the limits of what’s bearable. This was an epoch that beggared metaphor, a virus that struck, by the very nature of its transmission, the most beautiful, the most desired, the most free.”

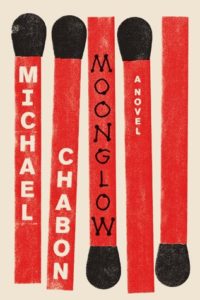

Michael Chabon, Moonglow

This week brings more glowing reviews of Chabon’s memoir/novel hybrid.

Maureen Corrigan (NPR) is a fan:

Moonglow “may be structured around the sentimental situation of a dying grandfather telling the secrets of his life to his grandson, but these stories, dozens of them chopped and scrambled, are bawdy and moving, violent and very funny. It’s as though the unnamed grandfather here is like Scheherazade, holding off death through an extended bout of yakking.”

“Back and forth the narrative moves,” writes Ellen Akins (Minneapolis Star-Tribune), “prompted and interrupted by the narrator’s questions, between the dying grandfather and the account he is supposedly giving of his past, all rendered in richly novelistic detail: the grandfather’s pursuit of Wernher von Braun, hero-turned-villain; the grandmother’s fatal allure and secret history; the mother’s sad, spunky accommodations. Threaded through it all is the wonder of the universe, the dream of spaceflight that has forever animated and frustrated the grandfather.”

Sam Sacks (Wall Street Journal) calls Moonglow “a bewitching work of Greatest Generation mythology.”